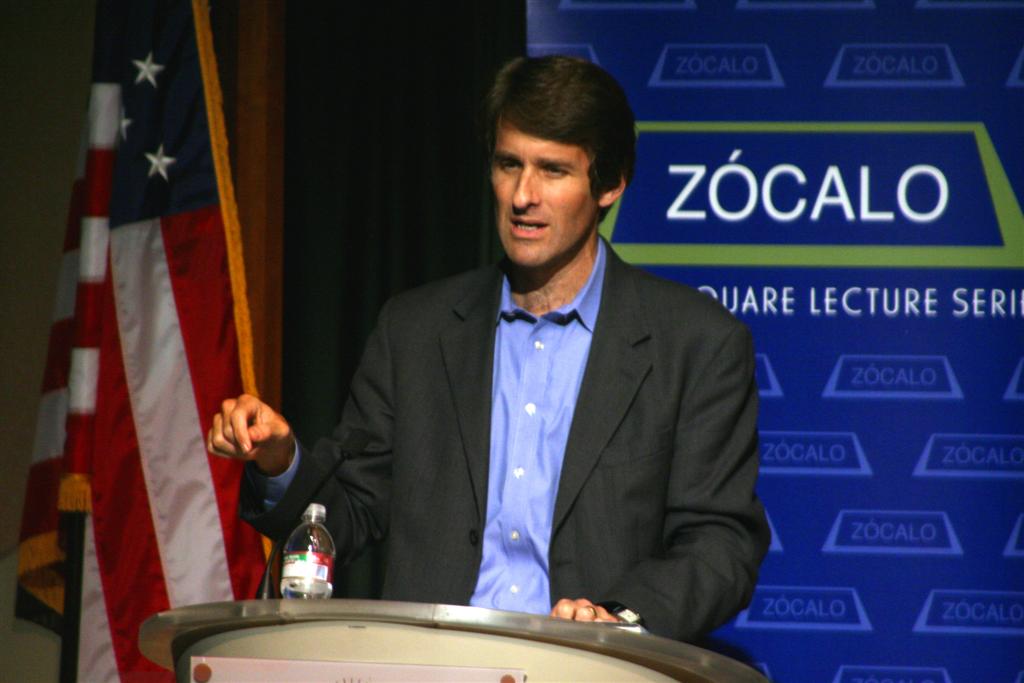

The spark of Edward Alden’s book, The Closing of the American Border: Terrorism, Immigration, and Security since 9/11, came from an L.A. story.

Nearly six years ago, when Alden, now a Bernard L. Schwartz senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, was still a journalist, he got a call from a Los Angeles-based immigration attorney about the travails of a young Pakistani doctor. He repeated it to a Zócalo audience at the Los Angeles Central Library: The doctor had won a permanent post at UCLA Medical Center, specializing in pediatric cardiothoracic surgery, and working under a foremost authority in the field, himself an immigrant from South Africa. For the new post, he needed a new visa, which required him to return to Pakistan. But delays in processing his visa left him languishing in Pakistan for months.

The tale spurred Alden on a study of how American security policy after 9/11, however well-intentioned, cast too broad a net, catching ordinary immigrants as well as suspected terrorists. Alden noted several other stories of innocent immigrants – initially welcomed to the U.S. to develop their talents in and contribute them to our country – caught in traps meant for would-be terrorists: the Sudanese doctor stranded at a conference in Brazil while his just-arrived family fended for themselves in the States; the Lebanese Christian man who failed to register himself as an immigrant from a Muslim country and got stuck continents away from his Mexican-American wife. It wasn’t always such, Alden said, and it doesn’t have to be so.

9/10

Before 9/11, Alden said, “The U.S. was the most open and some might have said the most naïve country in the world.” The goal of U.S. policy in that “golden age of globalization,” he said, was to encourage travel and immigration for economic and social benefits (though the 1990s too felt the hurt of anti-immigrant sentiment and crackdowns). It was quite a different country, it seemed than the one that, banned Chinese immigrants in a prior century, or rounded up Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II.

Before 9/11, Alden said, “The U.S. was the most open and some might have said the most naïve country in the world.” The goal of U.S. policy in that “golden age of globalization,” he said, was to encourage travel and immigration for economic and social benefits (though the 1990s too felt the hurt of anti-immigrant sentiment and crackdowns). It was quite a different country, it seemed than the one that, banned Chinese immigrants in a prior century, or rounded up Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II.

But in hindsight, for some American officials, that openness was dangerous. Of the 19 hijackers, Alden noted, a few had overstayed visas. Some, including ringleader Mohammad Atta and Flight 93 hijacker Ziad Jarrah, received speeding tickets in the days before the attacks, but aroused no suspicion.

9/12

The Justice Department concluded that “the best way we can prevent another terrorist attack is to use our immigration enforcement tools to the fullest,” Alden said. They came up with two plans: the first was to require extra scrutiny for visa applications from certain countries. (Muslim and Arab ones, that is, and “we threw in North Korea for good measure because we always throw in North Korea for good measure,” Alden joked.) The second was to require every noncitizen from a Muslim or Arab country to register with the government.

The result of more visa regulation? Big backlogs, for one. And as Alden, and some members of the audience in Q&A noted, was a terrorist watch list with hundreds of thousands of names; every organization from hospitals to orchestras suffering from visa strictures; tourism and foreign university applications dropping like stones; and America’s global image devolving from free to fortressed. “The easiest interview I arranged was Colin Powell. He wanted to talk about this,” Alden said. “He said every meeting this issue came up.”

Today

But Justice might have paid more attention to a lesson learned by customs officials decades earlier – one that points to a better road for U.S. policy, Alden said. In the 1980s, when drug trafficking was the chief national security issue, customs officials knew what to target – planes traveling to the U.S. from countries like Colombia and Bolivia – but not how. Searching and questioning every passenger would be too time-consuming (and would surely provoke irate letters to Congress, Alden said). Instead, Customs convinced airlines to voluntarily pony up passenger information – passport numbers, credit card details, location of purchase, whether tickets were one-way. The details helped Customs create profiles of international travelers and, Alden said, searches went down but seizures went up.

But Justice might have paid more attention to a lesson learned by customs officials decades earlier – one that points to a better road for U.S. policy, Alden said. In the 1980s, when drug trafficking was the chief national security issue, customs officials knew what to target – planes traveling to the U.S. from countries like Colombia and Bolivia – but not how. Searching and questioning every passenger would be too time-consuming (and would surely provoke irate letters to Congress, Alden said). Instead, Customs convinced airlines to voluntarily pony up passenger information – passport numbers, credit card details, location of purchase, whether tickets were one-way. The details helped Customs create profiles of international travelers and, Alden said, searches went down but seizures went up.

Thirty years later, Customs used those traveler details to turn up the name of the 19 hijackers within hours of the attack. A couple hijackers, they found, had been identified by the CIA as Al Qaeda operatives, but their names were handed to the State Department after visas had already been granted. “The lesson was, if we can do this after the fact, why can’t we do this before the fact?” Alden said. He cited some new policies like fingerprinting foreign travelers to the country, which (notwithstanding the inconvenience and muddled symbolism of ink-stained fingers) allow for better targeting. But big blunt measures remain, like border fences and local police acting as immigration enforcement (pioneered here in Southern California). “Defeating terror demands nuance and it demands balance,” Alden noted. So deeply restricting immigration, “the lifeblood of America’s economy” and “the foundation of its society and really its national power,” isn’t the way to go.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors