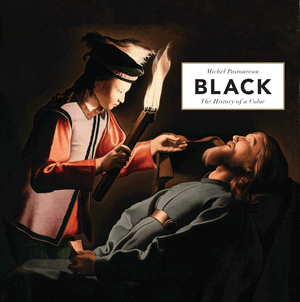

by Michel Pastoureau

If there is a villain in Michel Pastoureau’s Black: The History of a Color, it is Isaac Newton.

The scientist, whom Pastoureau does, admittedly, call the greatest of all time, appears three-quarters of the way through this chronological telling of the shade’s evolving symbolism in the worlds of art, fashion, religion, government and finance. In the anonymous portrait – one of several gorgeous selections appearing on likely half the handsome book’s pages – Newton is shrouded in black. He sits in a darkened room, the only spots of light are on his resting hands, a white cuff and color, his wavy gray hair, his preoccupied face, and, lurking in the background, a page of calculations.

Newton proved “scientifically” that black is not a color. The scare quotes are Pastoureau’s. He blames Newton for “domesticating” the colors, for making a science of what was once art and intuition. But Pastoureau still dwells in those realms (as he has in his past books on blue and stripes

), commenting on the impact of scientific and technological advances on the fate of black only when he must – the printing press and black ink, the industrial revolution and coal, the perfection of black dye, an ever so brief mention of black holes. And even when he stops to dwell on science he still believes a statement he makes in reference to the production of dark dye: “symbolism preceded chemistry.” Even social science is largely left out; Pastoureau speaks only briefly of the demonizing of dark-skinned people, giving it as much space as a list of the rare few “Christianized” non-whites, who escaped the stigma attached to their skin.

Pastoureau writes richly of the black of our more poetic and primitive selves, who see in it not simply the absence of color but rather the cold, dark hell of the Greeks, of death and melancholy. This is the black for those who are afraid of the dark, portentous black birds and unlucky black cats. It is a dual-toned black, matte and one glossy, ater and niger in Latin, swart and blaek in German. It is the color of the devil and his beasts – particularly boars – and also of penitence and humility, from Benedictine Monks to Protestants.

Much as Pastoureau tells of a color that has a hold on our guts, he also writes of the slow neutralization of the shade’s more potent symbolism. That story starts with Middle Ages heraldry, when black paint was used commonly without signifying evil. The black knights of yore, he notes, were heroes with hidden identities; red knights were the villainous ones. Anne of Brittany brought black mourning clothes to the French court; imperial rulers like Philip II of Spain wore it regally, alongside purples and grays (brown, Pastoureau writes in one of many interesting asides on other colors, remained a peasant’s shade). Lawyers and judges made black the official sponsor of secular law (executioners’ black clothes seemed at once somberly secular and frighteningly mystical). Businessmen and aesthetes adopted it as a sign of elegance. Woodcuts and prints made “black and white” a primary mode of seeing, a rival to “color,” as it remained in the golden age of movies and television.

Pastoureau only briefly discusses the last century, when film and photography became obsessed with shadow, when painters put ragged swaths of black on their canvases, when fascists, anarchists, rebels and punks adopted it as their uniform. All the tumult – the widening significance of the color, its ease of production, its steady use in so many media for drama – seems to finally neutralize black, leading Pastoureau to ask in closing, “Is it possible that black has finally become an average color?”

Excerpt: On the 19th century, “Everywhere the sense of melancholy triumphed: that century’s ill, which was for the Middle Ages a true illness – etymologically, an excess of black bile – became for the Romantic poets a required condition, almost a virtue. All poets had to be melancholic, to die young….”

Further Reading: Blue: The History of a Color and A Perfect Red

.

Send A Letter To the Editors