Much like obscenity, you know chick lit when you see it.

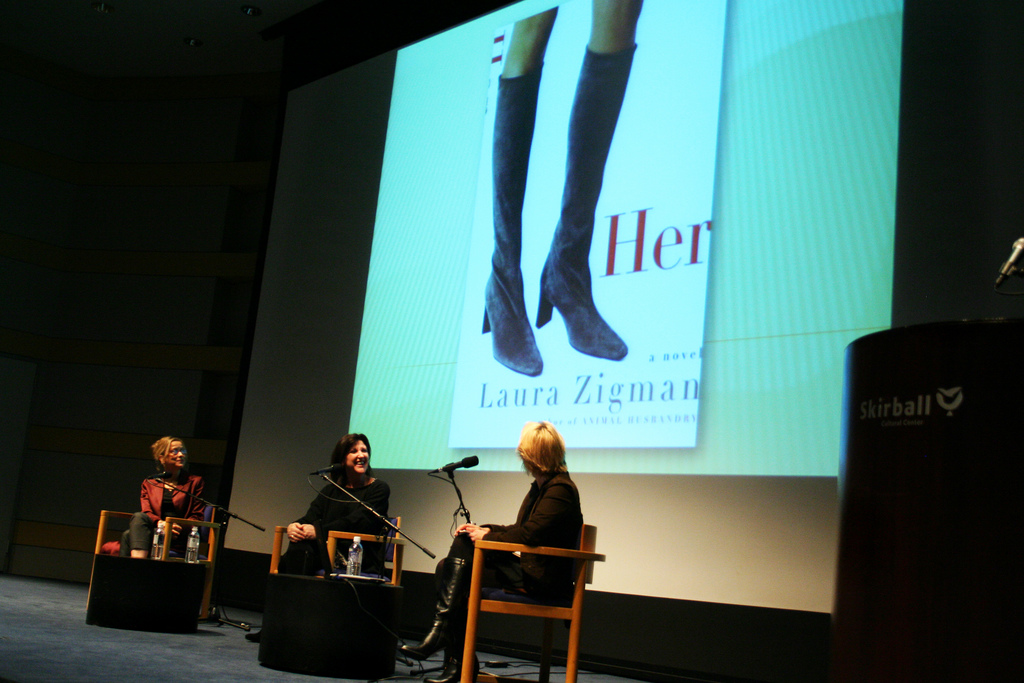

“Legs and shoes,” said moderator Meghan Daum to the mostly female crowd at the Skirball Cultural Center. As she skimmed through slides of over a dozen book covers, all emblazoned with well-shod or delicately barefoot gams, the crowd groaned, along with speakers Elisabeth Robinson and Laura Zigman, both novelists.

Beyond the covers, however, chick lit is hard to define. The term can be pejorative or just commercial shorthand. The subject can be frivolous or serious, formulaic or innovative, authentic or not. Sub-categories can include “teen chick lit” and “mommy lit” or even “hen lit“. And the genre itself, as the panelists discussed, can be considered hurtful or helpful to women.

Blame it on Bridget Jones

Robinson and Zigman both had their own book cover horror stories.

Robinson and Zigman both had their own book cover horror stories.

“I was shocked by how my book was packaged,” Robinson said. “There’s a little girl in a princess costume. There isn’t one in the book.” Zigman’s story was much the same – her latest novel, Piece of Work

, featured a naked baby’s bottom, though no baby appears in the story.

But both women understood the need to market a novel as chick lit.

“I probably benefited from the genre of chick lit,” Robinson said, noting that her experience as a film executive prepared her for the trials of marketing. “There’s high literature and Danielle Steele and chick lit and then there’s this middle category, and if you can’t get shoved into chick lit, you might not sell as many books.” Zigman, who spend ten years as a publicist in the book world, agreed. “If no one were buying them, they wouldn’t be there,” she said.

The demand coincides, Zigman noted, with several trends: a rise in the population of urban single women, a boom in huge chain bookstores and a rise in consumerism (many chick lit books, including the popular Shopaholic series, focus on shopping). The boom in the genre in the late 1990s – with the arrival of Bridget Jones’s Diary

, a work, Daum noted, that “was an indictment of the very culture that embraced it” – has allowed for more female writers to get published. And they’re writing for their industry’s primary audience – roughly 80% of book buyers are women, Robinson noted, adding that in the film business, “there was no shame associated with” making movies that appealed to the primary moviegoer, teen boys. But there is shame in writing chick lit (and with commercial success in general, Zigman noted).

“Who is generating this shame?” Robinson asked. “It’s not men, because they aren’t reading it.”

Why There is No Harriet Potter

The men who did read her book, Robinson noted, universally said that they never would have picked a book with a little girl on the cover, even though women routinely read stories about men and involving male themes.

The men who did read her book, Robinson noted, universally said that they never would have picked a book with a little girl on the cover, even though women routinely read stories about men and involving male themes.

“I think men are not interested in women’s stories,” she said. “J.K. Rowling made it Harry Potter, not Harriet Potter, for a reason.”

The disdain for literature by and about women is centuries old, as Daum and one audience member noted. More recently, Daum said, in 1959, Norman Mailer excoriated female writers (the Zócalo audience gave him a good booing). Writer Francine Prose asked whether there was a distinct, inferior female prose style (she concluded not). Novelist Diane Johnson proclaimed that male readers do not understand the female experience as universal.

Today, female writers are still underrepresented in major general interest magazines, Daum said, and in judging and receiving literary awards, meaning that even though women buy the books, men rate them. Women’s magazines, the panelists agreed, tend to want pieces that are “sappy and reductive and simple,” as Robinson put it, in response to a question from a female writer in the audience. And no matter what their subject and style, many female writers find their works packaged as chick lit.

“I’ve seen too many really complicated novels with complex thoughts and really thought-out themes and dark humor placed into this category because the author … is young, the author is a middle-class white woman,” Daum said. “People go out and buy the book and they say this isn’t what I signed up for. There are digressions in here!”

Meanwhile, the panelists noted, male writers discussing chick-lit-like subjects aren’t dismissed the way women are. Zigman called the lauded novelist Bret Easton Ellis

Meanwhile, the panelists noted, male writers discussing chick-lit-like subjects aren’t dismissed the way women are. Zigman called the lauded novelist Bret Easton Ellis “the original shopper,” because of his penchant for dropping brand names. Ian McEwan’s prize-winning Atonement

had a young girl at its center. Benjamin Kunkel’s Indecision

– proclaimed to be the male equivalent of chick lit – was taken more seriously by critics, Robinson noted, than a similar book by a woman might. Men have more freedom to be funny, too, the panelists said. (Unless, Zigman half-joked, the woman is British, in which case humor is allowed.)

“When a man writes a book, he’s just writing a book,” Zigman said. “It’s a book. It’s about something. It’s good or bad. It sells or it doesn’t sell.” With women, she added, “There’s an enormous Talmudic discussion about what it is.”

Our Books, Our Fault

But women – as evidenced from the audience and the panel itself – are part of that discussion, and may be part of the problem, the panelists acknowledged.

“Women are not as supportive of each other as they are of men,” Robinson said. “They still want men’s approval, and this has something to do with the awards business….the male reading community.”

Zigman posited that women have an “innate insecurity about themselves,” not only while writing, but more broadly with working versus raising a family. The way women’s writing is received won’t change, Zigman said, “until women get away from that self-loathing.”

Daum responded, to a round of laughter and applause from the crowd, “But then there would be no need for women’s magazines.”

Watch the video here.

See more photos here.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors