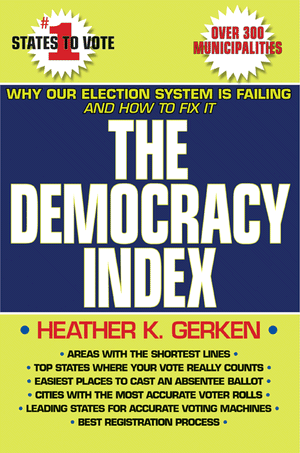

The Democracy Index: Why Our Election System Is Failing and How to Fix It

by Heather K. Gerken

About a year ago, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 to uphold an Indiana law requiring voters to present photo ID at the polls. Supporters praised the ruling for helping to fight voter fraud; detractors pointed out that there were no documented cases of such fraud. Both sides had something in common, however: an almost complete lack of evidence to support their claims.

The American election system suffers from an absence of statistics on how the system works and how it doesn’t, argues Heather Gerken. The Supreme Court, even, could only cite one historical example and one commission report to support its ruling (said commission report had little empirical evidence, too). Some of the statistics we do have are galling: in 2000, millions of votes were lost because of the registration process or other causes; in 2004, hundreds of thousands of poll workers were missing; 43% of election officials reported a voting system malfunction for the 2004 election, and 21% said poll workers didn’t understand their jobs.

Merely providing more detailed information of this kind would improve our chances of making every vote count, says Gerken, a Yale Law School professor and veteran of Barack Obama’s election-day “boiler room,” where staffers tried to make sure votes were cast and counted.

In her straightforward and brief book, Gerken advocates compiling this information into what she calls a “Democracy Index.” The index would reflect information about the “lived experience of the average voter” – whether everyone who wants to register and cast a vote can, and whether every ballot is counted correctly. The results, culled from samples of voters, would be weighted and transformed into an index divvied by state or even locality, spurring competition among election administrators, cracking through the partisan impasse around this issue, and taking advantage of our decentralized election regime. (Nearly every other developed democracy relies on national bureaucracies, not localities, to do the task.) It would bring the sort of statistical rigor common in the private sector – Wal-Mart, as Gerken notes, has a precise enough evidence-gathering system to know that sales of Pop-Tarts rise during hurricanes; the company ups its inventory accordingly.

Gerken is right to note that there’s something about indexes that make us pay attention, even for an issue as arcane and only occasionally headline-making (Florida in 2000, Ohio in 2004) as election reform. From the U.S. News and World Report college rankings to the Environmental Protection Index, they’re simple to understand but represent a broad compilation of data, and they put pressure on those at the bottom. Dan Etsy, the founder of the latter, reports to Gerken that countries immediately began competing after the release of his index, including at the top of the bracket.

Gerken is honest about the index’s potential shortcomings, most notably, perhaps, getting everyone to start compiling data (Gerken exhorts Congress to think in terms of open-source collection software). She suggests starting slow – acknowledging that the index will become more precise and expansive with time – and offers ways to prevent states from cheating. But Gerken’s bottom line is that more information is good in a system which even a major crisis – the 2000 recount – couldn’t change.

Excerpt: “…if it’s a mistake to conclude that the system is about to fall apart based on what occurred in Florida, it’s also a mistake to conclude that things are working well in the many places where a crisis has not occurred. When elections are competitive – when lots of new voters want to register, when turnout is high, when elections are decided by a small margin – we put more pressure on our creaky system than it can bear. It is precisely when we care most about an election’s outcome – when voters are energized and the race is hard fought – that we will be least confident about the results.”

Further Reading: The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States and The History and Politics of Voting Technology: In Quest of Integrity and Public Confidence

Send A Letter To the Editors