Carlos Moreno has held many titles city attorney; municipal, superior, and district court judge; and today, Associate Justice of the California Supreme Court. But foremost, he is an Angeleno.

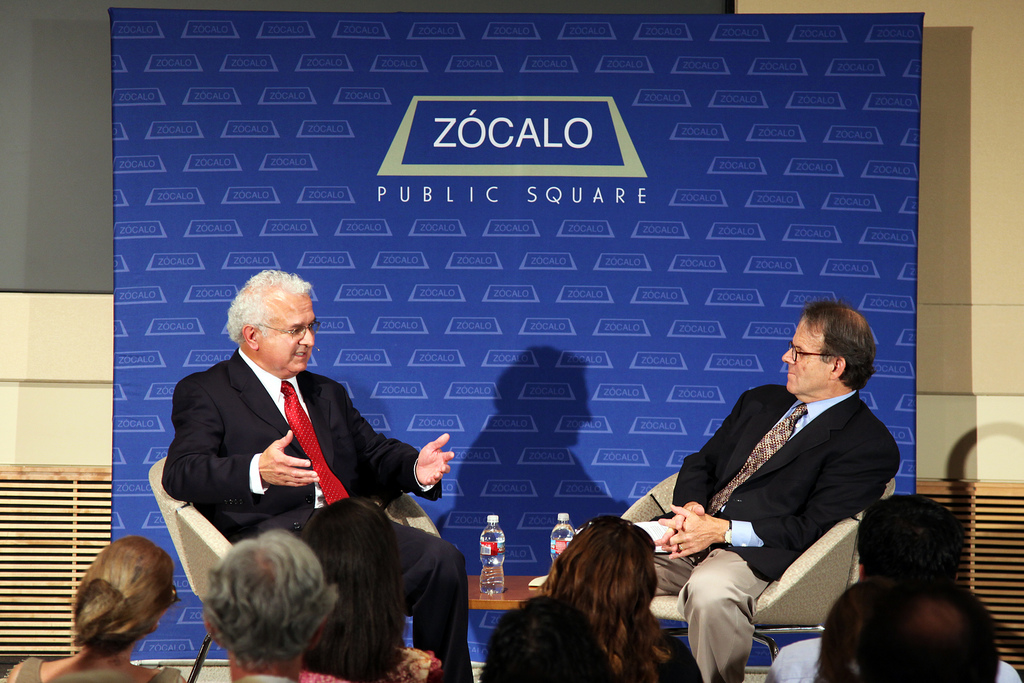

As University of California, Irvine law professor Henry Weinstein said to the packed audience at the California Endowment, Moreno grew up near downtown Los Angeles, the son of Mexican immigrants, attended its public schools and, between and after stints at Yale and Stanford, always returned to his home city. “He is clearly a man who feels very rooted in Los Angeles,” Weinstein said. And as Weinstein noted to applause, Moreno attended the very first game ever played at Dodger Stadium, in 1962.

Moreno, well-known now for his dissent in the recent Proposition 8 case and for being on President Barack Obama’s short list for the Supreme Court, appreciated the gracious introduction. “It’s not going to get much better than this,” he joked, “so can I leave now?” Moreno stuck around to talk about his recent landmark decision, his long career, and the nature of being a judge on one of the country’s most followed courts.

Proposition 8

In late May, the California Supreme Court upheld Proposition 8, which banned same-sex marriage. Moreno dissented, arguing that it violated the equal protection clause, which, he said, has long conferred “protection on classes of disfavored people…. To chip away at the concept of equal protection when analyzing human relations, and intimate human relations – it’s something you can’t do.” A limited exception to equal protection – as the majority of the court claimed it was making – means “you no longer have equal protection.”

In late May, the California Supreme Court upheld Proposition 8, which banned same-sex marriage. Moreno dissented, arguing that it violated the equal protection clause, which, he said, has long conferred “protection on classes of disfavored people…. To chip away at the concept of equal protection when analyzing human relations, and intimate human relations – it’s something you can’t do.” A limited exception to equal protection – as the majority of the court claimed it was making – means “you no longer have equal protection.”

The basis of offering gays and lesbians equal protection came in some part from the California Supreme Court’s ruling in 2008, in which, Moreno said, the court found gays and lesbians to be what’s called a suspect class – a limited set of groups, defined by race, ethnicity, or nationality, conferred special status and special protection under law. The U.S. Supreme Court does not grant that status to groups by gender, Moreno noted. The California court erred in conferring that status on sexual orientation and then claiming an equal protection exception, Moreno said.

Bookends

The gay marriage case, had it ended differently, might have been something of a “bookend” to Moreno’s career. He was born in 1948, the year the California Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling allowing interracial marriage, preceding the U.S. Supreme Court by nearly two decades. “Sixty years later,” Moreno said, “our court made its landmark ruling on sexual orientation, and I see that as a bookend in terms of my life experience. I thought it would be a firm bookend, but it didn’t turn out to be so.”

The gay marriage case, had it ended differently, might have been something of a “bookend” to Moreno’s career. He was born in 1948, the year the California Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling allowing interracial marriage, preceding the U.S. Supreme Court by nearly two decades. “Sixty years later,” Moreno said, “our court made its landmark ruling on sexual orientation, and I see that as a bookend in terms of my life experience. I thought it would be a firm bookend, but it didn’t turn out to be so.”

Noting the time it took for the country to adopt California’s attitude toward interracial marriage, he speculated that the outlook for gay marriage wasn’t so promising. Though a handful of states have legalized it, a consensus among states and society, Moreno said, was unlikely to occur in his lifetime. Even as the U.S. Supreme Court okayed interracial marriage, popular opinion was likely against it, Moreno noted. “Whether society will change first or the law will change is a close guess,” he said. “But I hope the law will take the lead as it did with respect to interracial marriage.”

Diversity on Bench

Though Moreno said during Q&A that his Prop. 8 decision absolutely did not impact his chances for a future Supreme Court seat, and he didn’t imagine the public would take out its frustrations on the court, he and Weinstein discussed the nature of the appointment process, and the importance of diversity on the bench. Though the process appointees to the California Supreme Court undergo is an exhaustive one, Moreno noted, the appointment process for the Supreme Court has become increasingly politicized since Robert Bork’s rancorous nomination and rejection nearly 20 years ago. “That’s when the whole process became so intensely political. People would come out of the woodwork to comment on your qualifications or disqualifications for the position,” Moreno said. “Senators increasingly took positions not so much to discredit the candidate, but really to expound their political views and ideologies.” Judge Sonia Sotomayor, he said, is enduring the same, given that, Moreno said, her jurisprudence is fairly “mainstream,” and she is well-qualified.

Obama’s push to nominate a woman of color, though, is one that Moreno seemed to appreciate. Diversity on the court, he said, is “extremely important…if only for the sake of the appearance of justice.” Both the California and national benches, Moreno noted, were once “very, very segregated.” Not only does diversity on the bench encourage citizens to “buy into the justice system,” Moreno said, but it also helps for a court to have a multiplicity of views, from judges of varying racial, economic, and social backgrounds. But, Moreno joked, he didn’t quite want to say diversity makes courts “better”, because “that got Sonia Sotomayor in trouble.” Still, empathy is key on the bench – Moreno has been credited for having empathetic decisions – because judges, Moreno noted, “insert a human element,” going beyond the way Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. characterized the role, as “an umpire calling balls and strikes.” As Moreno joked, “judges also determine the strike zone.”

Obama’s push to nominate a woman of color, though, is one that Moreno seemed to appreciate. Diversity on the court, he said, is “extremely important…if only for the sake of the appearance of justice.” Both the California and national benches, Moreno noted, were once “very, very segregated.” Not only does diversity on the bench encourage citizens to “buy into the justice system,” Moreno said, but it also helps for a court to have a multiplicity of views, from judges of varying racial, economic, and social backgrounds. But, Moreno joked, he didn’t quite want to say diversity makes courts “better”, because “that got Sonia Sotomayor in trouble.” Still, empathy is key on the bench – Moreno has been credited for having empathetic decisions – because judges, Moreno noted, “insert a human element,” going beyond the way Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. characterized the role, as “an umpire calling balls and strikes.” As Moreno joked, “judges also determine the strike zone.”

Health and Death in California

Moreno commented on two other major challenges for the California courts: the death penalty and social services. Weinstein and Moreno agreed that when it comes to the death penalty, the California system is “schizophrenic,” legalizing the death penalty but poorly enforcing it. Death penalty cases take up a quarter of the Supreme Court’s workload, Moreno said, and 20 years often elapse between a judgment and an execution, when it occurs at all. The state has had only about a dozen executions in the last two decades, Moreno noted, and the leading causes of death on death row are old age and suicide, rather than execution. Holding the 680 inmates on death row, Moreno estimated, likely costs more than giving them life without parole.

Moreno commented on two other major challenges for the California courts: the death penalty and social services. Weinstein and Moreno agreed that when it comes to the death penalty, the California system is “schizophrenic,” legalizing the death penalty but poorly enforcing it. Death penalty cases take up a quarter of the Supreme Court’s workload, Moreno said, and 20 years often elapse between a judgment and an execution, when it occurs at all. The state has had only about a dozen executions in the last two decades, Moreno noted, and the leading causes of death on death row are old age and suicide, rather than execution. Holding the 680 inmates on death row, Moreno estimated, likely costs more than giving them life without parole.

Moreno also has firsthand experience with California’s social service system, as the adopted parent of a developmentally disabled daughter. “On a good day, I know a little bit about the law,” Moreno said to a laugh from the crowd. “But to be able to obtain…the whole panoply of services that a young girl would need in her condition was very difficult for even someone like me, who knows something about the law, who is able to take time off, who has a fax machine, who has a secretary.” Moreno works to support legal service providers, and chairs committees on foster care in the state. He called the latest cuts in foster care – denying funding for about 900 social workers statewide – “disastrous.” While he didn’t propose how best to improve care, and to simplify the system beyond making it more user-friendly, he said, “It’s just unfortunate that when the cuts are made, they’re made against the most vulnerable.”

A Day in the Life

Though he acknowledged California’s problems with its healthcare, Moreno said during Q&A that he didn’t have a particular opinion on whether the state needed a constitutional convention. He admitted that the judiciary would benefit from better funding to strengthen its impartiality. But, he noted, “I actually think we have a pretty good system in California.” He also appreciated that trial judges are put up for election every dozen years. “There are some concerns there that an interest group can challenge a judge not with a candidate, but with an issue,” he said during Q&A. “By and large, I think people respect the work that we do as judges, and that’s not the case in so many other states.”

Though he acknowledged California’s problems with its healthcare, Moreno said during Q&A that he didn’t have a particular opinion on whether the state needed a constitutional convention. He admitted that the judiciary would benefit from better funding to strengthen its impartiality. But, he noted, “I actually think we have a pretty good system in California.” He also appreciated that trial judges are put up for election every dozen years. “There are some concerns there that an interest group can challenge a judge not with a candidate, but with an issue,” he said during Q&A. “By and large, I think people respect the work that we do as judges, and that’s not the case in so many other states.”

The California Supreme Court remains one of the most followed courts in the state, Moreno noted, and its justices maintain an emphasis on reaching consensus. Though Moreno said that it’s harder to persuade three justices to agree with you that it is to persuade one (on the Circuit Court of Appeals), or to make solo rulings as a trial judge, he appreciated the California bench’s method, by which the justices confer before and after oral arguments and try to reach consensus. The decisions that result “may be more narrow,” Moreno admitted, “but generally I’m of the belief that the law should develop incrementally. We can’t take off the big bite, we take off the small bite, and there will always be another case coming down the road.”

Watch the video here.

See more photos here.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors