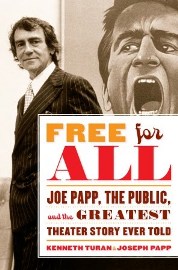

Kenneth Turan, film critic for the Los Angeles Times, started to collect the material for Free for All: Joe Papp, The Public, and the Greatest Theater Story Ever Told over two decades ago. He shared with Zócalo the story behind the story and why Joe Papp transformed theater.

Q. Tell me the story behind the book. Why did it take so long to get to print?

A. I signed the contract for this book in 1986. It was to be an oral history of the New York Shakespeare Festival, put together in collaboration with Joe Papp, who founded and ran the festival and the Public Theater. I worked on it for close to two years. I interviewed about 160 people, and I amassed somewhere around 10,000 pages of transcript. I turned that into a first draft that was 1,100 or 1,200 pages, really too big to be published, but that was the first draft. Joe read it and decided that he wasn’t going to go further, that he didn’t want the book. That was very disturbing.

A. I signed the contract for this book in 1986. It was to be an oral history of the New York Shakespeare Festival, put together in collaboration with Joe Papp, who founded and ran the festival and the Public Theater. I worked on it for close to two years. I interviewed about 160 people, and I amassed somewhere around 10,000 pages of transcript. I turned that into a first draft that was 1,100 or 1,200 pages, really too big to be published, but that was the first draft. Joe read it and decided that he wasn’t going to go further, that he didn’t want the book. That was very disturbing.

My feeling at this point, looking back on it, was that he read my first draft at a point of real crisis in his life. He had just found that that he had the cancer that would kill him within three years. He had found out that one of his sons had AIDS that would kill him within three years. The first draft of books like this need to involve a back-and-forth, and he wasn’t in the frame of mind to do it.

Q. How did you move past that?

A. Mostly I went into shock. This was a lot of work over two years, and I thought it was some of the best work I’d ever done. To just have it be stopped like that was really shocking. There was a number of years – I can’t remember how many, but at least a dozen – that the manuscript of my first draft just sat in a box. I couldn’t even bear to look at it, and I didn’t want to talk about it. I didn’t even want anyone to commiserate with me. It was too awful to deal with. The book wouldn’t leave me alone, though. I couldn’t really move on or give up on it. Obviously I moved on in some ways – I took a job at the Los Angeles Times and a lot of things happened, but I couldn’t let the book go. I wrote a letter to Gail Merrifield Papp, who was the director of play development at the Public, and Joe’s widow. I basically said this book is too important to die, and is there any way we can resurrect it? She thought that there was. Because I had this job at the L.A. Times, working on it took longer than it might have otherwise. By the time everything came together and a new draft was finished and sent to be published, lo and behold it had been 23 years.

Q. When was the first time you encountered the Shakespeare Festival?

A. I was exposed to it in high school. My sister took me, and I thought it was tremendously exciting. It was free, and you could just go and sit in the theater and see the plays. Like most people in the early days of Shakespeare in the Park I was a newcomer to Shakespeare – I didn’t have a history of seeing his work performed. I’d studied him, but it was very exciting to see his plays performed. That was Joe’s whole notion of what Shakespeare in the Park should be. When he started, he took a portable theater to the toughest neighborhoods in New York. He parked his truck and constructed a stage and put on Shakespeare for people, and they liked it.

Q. Why did he pick Shakespeare to take to the public for free?

A. The main reason is, I think, that when he grew up, he was a very, very poor kid. He hated even to talk about how poor he’d been. It was the kind of poor that his family would move in the middle of the night because they couldn’t pay the rent. It was next-door-to-homelessness poor. In high school he was exposed to Shakespeare. He had one of those charismatic teachers who make such a difference in people’s lives. He went for it – it spoke to him. It focused his life. And he felt that what had worked for him could work for other people. For his entire life he loved Shakespeare and directed the plays himself. He had an endless passion for the work.

Q. How did his work change the New York theater scene? Was it seen as much more elitist before he established the Public?

A. There is a quote from David Hare in the book, who is one of the top British playwrights. He said, “Joe’s genius, if you like, was for understanding that if you want to set up an institution to fight the crappiness of values, the crappiness of the failure-success syndrome, it can’t be on the fringe. He understood that you had to fight with an institution which was as large and as powerful as the commercial institutions.” That’s where Joe was different. There had always been free or inexpensive plays and small theaters, but to have an institution with the values of small theaters that was big and powerful and attracting everyone – that was something different. That was an audacious idea. Joe was always going in and battling with mayors and people who would say, “We have no money, we have to pay for schools, we can’t afford theater.” He wouldn’t hear it. He would say, “Theater is just as important.” He would not be denied. He would yell at donors if they hadn’t given enough money – which of course usually people don’t do. He said to one donor – I forget who it was – “You’re lucky you have a place like mine to give your money to. You’re fortunate to have a place like the Public Theater.” He was the opposite of a supplicant. He was a true believer. Before he joined World War II he had been very politically active, he had been a socialist and a communist, which got him into trouble during the McCarthy years. But that belief in art for the masses was something really was a constant throughout his entire life. He really believed it. It wasn’t a cover for ambition or something else. Whatever people said about Joe – and people said all kinds of things about him – nobody ever said this guy was insincere.

Q. How did Shakespeare in the Park become such a phenomenon around the country?

A. In terms of Shakespeare in the Park and free and outdoor plays, Joe’s efforts were widely emulated. In terms of building an institution of the size of the Public, I don’t know that anyone has been able to do that. Gordon Davidson came the closest here, but it has not been done a lot.

Q. How is theater faring today? Does it still have an elitist and distant image?

A. We always need more Joe Papps. When I did the research for this book, and did the interviews in 1986 and 1987, everyone knew that Joe was not the easiest person to deal with. He made his share of enemies. One of my favorite stories is when he ran into a playwright shortly after they had had a huge, screaming fight. Joe comes over and starts to chat amiably with the playwright, who says, “Why are you talking to me? We had this big fight.” And Joe said something like, if I didn’t talk to the people I had fights with I wouldn’t have anyone to talk to.

When he was alive, people who were not happy with him would say yes, he’s accomplished a lot, but if he didn’t do it, someone else would. But the reality is, since his death in 1991, no one has done what he did. In New York, he made theater central in a way no one else has managed. You had to pay attention to the Public if you were a culturally involved New Yorker. That has been hard to duplicate.

*Photo courtesy wallyg.

Send A Letter To the Editors