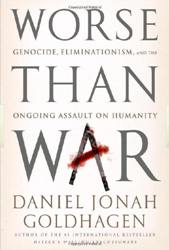

Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity

by Daniel Jonah Goldhagen

–Reviewed by Adam Fleisher

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen made quite a splash when he blamed ordinary Germans for the Holocaust in Hitler’s Willing Executioners. His newest effort isn’t quite as controversial, though it aspires to be equally dramatic. “Hundreds of millions of people are at risk of becoming the victims of genocide and related violence,” warns the first sentence of Worse Than War. But if we can make sense of these mass killings, Goldhagen argues, and build upon that understanding to develop an effective response, we “will save countless lives and also lift the lethal threat under which so many people live.”

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen made quite a splash when he blamed ordinary Germans for the Holocaust in Hitler’s Willing Executioners. His newest effort isn’t quite as controversial, though it aspires to be equally dramatic. “Hundreds of millions of people are at risk of becoming the victims of genocide and related violence,” warns the first sentence of Worse Than War. But if we can make sense of these mass killings, Goldhagen argues, and build upon that understanding to develop an effective response, we “will save countless lives and also lift the lethal threat under which so many people live.”

To that end, Worse Than War begins expanding genocide to the concept of “eliminationism.” The core of Goldhagen’s argument is that the “the desire to eliminate peoples or groups should be understood to be the overarching category and the core act.” To the perpetrators, the means – repression, expulsion, prevention of reproduction, and extermination – are more or less functional equivalents. In the course of a review of the horrors of the 20th century, Worse Than War makes the argument that eliminationist assaults, like wars, are ultimately political acts. Political leaders – and genocides always have leaders – perpetrate genocide for the same reason they go to war: to achieve a political outcome. Just as we can create disincentives for instigating war, and fight defensive and protective wars, so to can we meet genocide head on. In Goldhagen’s words, “Mass elimination is always preventable and always results from a conscious political choice.”

Goldhagen’s passion is admirable. But the take-no-prisoners tone of Worse Than War can be a bit overwhelming. The word “must” appears with striking frequency; Goldhagen’s moral outrage seems to have translated into a moral certainty that can come across as bullying. Larger messages get lost in the condemnatory language the book frequently uses. For instance, he argues that the Genocide Convention, ratified in 1948, has “severe and ridiculous” definitional problems, suffers from an “even more problematic” failure to define genocide, and has not only an “even more crippling aspect” and “another grave problem,” but also another “colossal problem.” Even though it was an “immense failure,” it was also “immensely important” because it is the only formal convention empowering military intervention against genocide. In other words, the convention was a seminal moment in the history of efforts to end genocide – something that can be developed, in spite of its flaws. Goldhagen is analytically perceptive, and his research is precise and detailed, but he tends to shed perspective in the face of righteousness.

The last section of Worse Than War, titled “Changing the Future,” starts with modest suggestions like hounding the media into better covering genocides. The resulting awareness will create a “new, more accurate, more powerful anti-eliminationist and pro-human discourse about mass murder and eliminations.” But what Worse than War is really about is more war. Genocide must be met head on, “with a single-minded effort and full force…. Humanity must engage a war against humanity with all possible military means to safeguard itself.” Goldhagen argues that the current international system, based on sovereignty and therefore inhospitable to nondefensive war, “effectively and as a practical matter sanctions mass murder.”

Scrapping the existing international system in order to turn nondemocratic regimes out of power before they can commit genocide is certainly an ambitious project, to say the least. Like his previous works, Goldhagen’s Worse Than War will certainly stimulate debate about how genocide can be prevented, and about how far we should go to prevent it. But the author’s dream solution will, sadly, probably remain just that.

Excerpt: “Mass murder is a political act. It is not a frenzied outburst of crazed individuals. It is not the lashing out of a psychically or materially wounded collectivity. It is not a suprahuman or historically determined occurrence caused by prior acts of people long dead or continents away. It is not the mere expression of modernity’s conditions or bureaucracies, or the explosive result of social psychological pressures. It is not driven by the darker, barbaric self supposedly within us all…. Because mass murders and eliminations are political acts, to understand and account for them, we must reinsert them into our understanding of politics and fundamentally change or expand our conception of politics to include them.”

Further Reading: Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed and A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide

Adam Fleisher is a law student at the University of Virginia.

*Photo courtesy hamsterschreck.

Send A Letter To the Editors