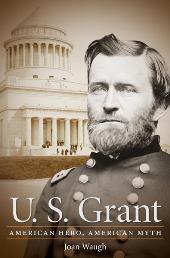

U. S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth (Civil War America)

by Joan Waugh

That Ulysses S. Grant’s most visible commemoration – his scowling and sad portrait on the fifty-dollar bill – came out on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash is cruelly fitting. Like the market, Grant’s reputation towered before it collapsed suddenly sometime in the early part of the 20th century.

That Ulysses S. Grant’s most visible commemoration – his scowling and sad portrait on the fifty-dollar bill – came out on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash is cruelly fitting. Like the market, Grant’s reputation towered before it collapsed suddenly sometime in the early part of the 20th century.

The difference is that Grant’s memory has mostly stayed sunk. A statue of the general astride his favorite horse, Cincinnati, is mostly disregarded in Washington, DC, now crowded with much bigger monuments. His official memorial – known by most as Grant’s Tomb and as the subject of a Groucho Marx riddle – makes no attempt to woo tourists with plaques or pamphlets detailing his presidency. Even if some lone traveler were persuaded to stay a while, he would have to head elsewhere to find a restroom. By the end of the last century, graffiti covered the mausoleum, skateboarders and addicts were the most likely visitors, and, when a renovation project was launched, John Tierney asked in The New York Times, “Are we going to let a corpse extort money from us?” In 2005, attempts were even made to shove him off the $50-note, in favor of Ronald Reagan.

Joan Waugh’s U.S. Grant asks why the man once credited with holding the Union together – first with force and then with federal power – has fallen so low in historical memory. Traversing the many existing accounts of Grant’s life and his own writings, Waugh leaves the presidency to a slim chapter and the gritty tactics of war to a few parts. She focuses instead on his rise to war hero and the White House, and later on his post-presidential world tour, his gasping rush to write his memoirs before succumbing to throat cancer, and his million-mourner-strong funeral. Waugh finds that the ground shifted under Grant after the 1920s. The South started to be seen not as defeated territory, but as noble lost cause; the Union went from precarious parts to indisputable whole, negating the need to remember all the men who held it together. Abraham Lincoln and Robert E. Lee – tragic and romantic figures – rose in estimation while complex Grant slumped into history.

Grant’s life see-sawed between achievement and disappointment. From his rural farmland hometown he won admission to West Point, where instead of schoolwork he preferred reading James Fenimore Cooper and painting landscapes with Robert Walker Weir. He served smartly as a lieutenant in the Mexican American War – promoted after he searched for ammunition in enemy streets, strapped against the side of his horse to avoid getting shot. But he came home to bad investment schemes and life in a log cabin he built and named “Hardscrabble.” His Civil War victories were legend, as was his etiquette, particularly at the final surrender, but some critics already had started to dismiss him as the leader of a bloody mob campaign.

Grant might have been the most reluctant winner of the presidency. As he wrote to his wife, “I am afraid I am elected.” His failures as a president are well-worn ground. Waugh highlights his victories – a peaceful Indian policy, the passage of the 15th Amendment, his development of a foreign policy for a fledgling global power on the cusp of urbanization, industrialization, and mass immigration. His second term was marred by economic busts and panics and torn apart by a Reconstruction policy that was a disappointment. Grant even apologized, with a combination of candidness and the now familiar presidential passive voice: “Mistakes have been made, as all can see and I admit.”

The most victorious and strangest moment of Grant’s post-presidency has, Waugh notes, been dismissed by historians as a fluke or a spectacle ill-suited to a former president. But Waugh recasts Grant’s world tour as his embodying and spreading the image of a powerful and prosperous America. He encountered throngs of foreign admirers and met King Leopold II, Georges Clemenceau, and Otto von Bismarck, whom he told, “I am more of a farmer than a soldier. I take little or no interest in military affairs.” But Grant’s life after the White House was marked, too, by financial woe so grave and embarrassing that it persuaded Congress to create pensions for former presidents.

Waugh devotes much study to Grant’s final turns on the stage – his memoirs and his funeral. The funeral’s religious, emotional, carnival atmosphere Waugh recreates meticulously, noting how crucial the “pageantry of woe” was in the decades after the bloddy Civil War, and how both halves of the country managed to honor Grant (even if, in some Southern cities, the only open mourners were former slaves).

It’s Grant’s memoirs that might have made his sound reputation stick. Even at one-thousand-plus pages, published posthumously, the brick of a book was a big seller, touted by Mark Twain, Edmund Wilson, and Gertrude Stein. Grant’s writing was simple and direct. He settled no scores, made no big confessions and offered only indirect self-defense and mild apologies. Despite the vagaries of his reputation since, Grant, always a wise observer and correspondent, won where many presidents have failed: to have if not the final then at least the best-written word.

Excerpt: [On Grant’s funeral] “More than a million and a half spectators jammed the streets, perching on window ledges, climbing on statues and up trees, sitting on the porches of empty houses, straddling the tops of lampposts and telephone poles, crowding dangerously onto rooftops. By early afternoon, people backed up along the bluffs above the Hudson River, where numerous sailboats bobbed on the sparkling water, and five men-of-war waited in line for the signal to fire their salutes…. Enterprising vendors sold three-legged wooden stools for twenty-five cents and souvenirs such as black silk mourning ribbons, busts, and pennants with “Grant” emblazoned across the front. Others sold lemonade, cider, and food, offering relief for the hungry and thirsty. Twenty miles of crowds, respectful and subdued (the New York City police had arrested all known pickpockets and troublemakers) watched….”

Further Reading: Ulysses S. Grant : Memoirs and Selected Letters : Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant / Selected Letters, 1839-1865 (Library of America) and The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture (Civil War America)

*Photo courtesy Jeff Kubina.

Send A Letter To the Editors