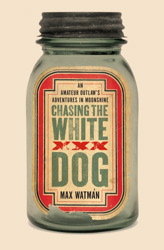

Chasing the White Dog: An Amateur Outlaw’s Adventures in Moonshine

-by Max Watman

Max Watman traces the popular stereotype of the moonshiner back to an 1877 issue of Harper’s Weekly, which sent an undoubtedly genteel New York writer on assignment to Kentucky to observe the strange specimen: “Clad in garments of butternut, sometimes yellow, oft-times brown, and occasionally blue jeans, and always homespun, with hands in pockets …the moonshiner on arriving in Louisville, where all of his kind are brought after their capture, waddles awkwardly through the streets, with an expression upon his features, if not of awe, most certainly astonishment of the deepest dye.”

Max Watman traces the popular stereotype of the moonshiner back to an 1877 issue of Harper’s Weekly, which sent an undoubtedly genteel New York writer on assignment to Kentucky to observe the strange specimen: “Clad in garments of butternut, sometimes yellow, oft-times brown, and occasionally blue jeans, and always homespun, with hands in pockets …the moonshiner on arriving in Louisville, where all of his kind are brought after their capture, waddles awkwardly through the streets, with an expression upon his features, if not of awe, most certainly astonishment of the deepest dye.”

But in Chasing the White Dog, Watman finds quite different kinds of moonshine men – starting with the earliest American colonists – and toys with becoming one himself, detailing thoroughly his often failed experiments. Some of Watman’s moonshiners seem straight out of lore – living and dying like cinematic outlaws, bearing names like Jaybird Philpott and Popcorn Sutton and Johnny McDonald. Some are present-day con artists who lace liquor with bleach and sell it to down-and-out customers of illegal bars. But most are devoted connoisseurs in it for the art or the science or simply the old American tradition of making booze, legally or illegally.

In early America, making alcohol was legal and untaxed, and “distilling a harvest of grain was simply good farming,” Watman notes. Finns, Germans, and Scots-Irish were devoted practitioners. But Alexander Hamilton’s proposed Whiskey Tax ended that era. Poor protesters of the tax, “drunk and armed,” ran off with their stills rather than face off against George Washington’s 13,000 troops. They started the split, Watman writes, between the legal distilling industry and black-market makers – not to mention solidified the one between Federalists and Jeffersonians, and between regulators and free-enterprisers.

When Jefferson repealed the tax, whiskey boomed – there were 14,000 distilleries in 1810, compared to about 20 major and 150 small ones today. Bourbon was born, thanks to land grants for corn growers. “You can’t eat 60 acres of corn,” Watman writes. “You’ve got to drink it.” But the tax came back during the Civil War, and increased tenfold. The moonshine man was “midwife by the stroke of Lincoln’s pen.” The biggest outfit, run in cahoots with the Ulysses Grant administration, made $2 billion a year in today’s dollars.

Prohibition marked the next great government move to control the alcohol market, and to make it a primarily legal, well-regulated, and more centralized business. As Watman sees it, “Since that result is so in line with the historical goals of the federal government, it seems barely a stretch at all to suggest that perhaps that was the real ambition of Prohibition.”

Watman spends a lot of time in the thick of today’s moonshining world. Though the scale of such activity is hard to pin down, Watman knows it’s still a booming business – the alcohol is more expensive than your average liquor store handle – and that most of it is sold in Philadelphia, far from imagined moonshine country. He lurks around stores and suppliers, trying to buy the goods for his own distilling activities without blowing his cover, and manages to make some decent booze after dangerous early experiments. He drinks something like “experimental kerosene-powered mouthwash” from a “nip joint,” or illegal bar. He shoots the breeze with law enforcement, and he attends a trial and finds himself siding with the defense. But the real future of distilling Watman finds at the first-ever distillers’ conference, where he meets makers of small local brews who are changing or working within laws, “little guys” making good products for little to no profit, the sort of devotee lost to taxes and regulation somewhere along the way.

Excerpt: “…farmhouse stills were common, and they were an integral part of the cultures the early settlers brought with them to America. This country was founded by distillers. The bedrock of America’s idealized notion of itself, the buffalo shooters, the deer-skin-clad men who battled and befriended nature and the Cherokee to survive, held kin and autonomy paramount, and they held whiskey a close third. The first Finns to hit these shores, the so-called ‘axe-wielders,’ were slash-and-burn farmers who threw their improvised hunting shanties together from felled trees and torched the rest of the timber so they could plant rye in the ashes….”

Further Reading: Driving with the Devil: Southern Moonshine, Detroit Wheels, and the Birth of NASCAR and Race Day: A Spot on the Rail

*Photo courtesy yvescosentino.

Send A Letter To the Editors