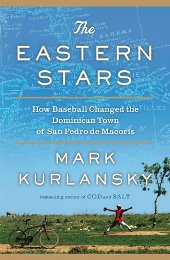

Mark Kurlansky, best-selling author of Cod and Salt

, spent several years covering the Caribbean for the Chicago Tribune in the 1980s, when he first came to the town to which he devotes his latest book, The Eastern Stars: How Baseball Changed the Dominican Town of San Pedro de Macoris

. “If you spend any time there, you know baseball is there. You see it everywhere,” he said. Below, he chats with Zócalo about how baseball arrived on the island along with sugar cane, how Dominicans came to love baseball, and how Dominican players in the U.S. affected American notions of race, immigration, identity and the game.

Q. How did baseball get to San Pedro?

A. It has to do with sugar cane. San Pedro was originally a fishing port, and I’m always drawn to fishing ports. Then it became a center for the sugar industry in the second half of the 19th century. There was a big sugar boom the sugar companies – about eight of them – established themselves in San Pedro. They were all run by either Americans or Cubans. This was in the 1870s and 1880s, a time when baseball was a real craze in both the U.S. and Cuba. Sugar mills only operate for about half the year, and that’s a good year. So you have this work force with nothing to do the rest of the time. There was always a labor shortage in the Dominican Republic. The soil is pretty rich, and most Dominicans would rather ply a little plot of their own than have an underpaying job at the sugar mill, so they could never get enough Dominicans to work these sugar operations. They brought in cane workers from what was then the British West Indies – sugar was failing in the British islands, and they had never adjusted to the end of slavery. These people came over and didn’t have work for much of the year, so they’d play cricket. And there were all of these sugar executives – Americans and Cubans – obsessed with baseball, and this idle workforce standing around swinging bats. So they gave them baseball bats. All the mills had teams, and they all played each other in the off-season for sugar. It was very high quality baseball.

A. It has to do with sugar cane. San Pedro was originally a fishing port, and I’m always drawn to fishing ports. Then it became a center for the sugar industry in the second half of the 19th century. There was a big sugar boom the sugar companies – about eight of them – established themselves in San Pedro. They were all run by either Americans or Cubans. This was in the 1870s and 1880s, a time when baseball was a real craze in both the U.S. and Cuba. Sugar mills only operate for about half the year, and that’s a good year. So you have this work force with nothing to do the rest of the time. There was always a labor shortage in the Dominican Republic. The soil is pretty rich, and most Dominicans would rather ply a little plot of their own than have an underpaying job at the sugar mill, so they could never get enough Dominicans to work these sugar operations. They brought in cane workers from what was then the British West Indies – sugar was failing in the British islands, and they had never adjusted to the end of slavery. These people came over and didn’t have work for much of the year, so they’d play cricket. And there were all of these sugar executives – Americans and Cubans – obsessed with baseball, and this idle workforce standing around swinging bats. So they gave them baseball bats. All the mills had teams, and they all played each other in the off-season for sugar. It was very high quality baseball.

Q. Was sugar a big industry elsewhere, and if so, did baseball follow?

A. No, except for La Romana, the next town over, where baseball did catch on. Sugar was centered in San Pedro, and it spread to La Romana. The other centers were baseball caught on were the two major cities, which weren’t sugar cane places but had Cubans and Americans for other reasons.

Q. Does baseball – as it does, or at least did, for the U.S. – shape the Dominican identity?

A. In San Pedro and in a lot of other places, all of the poor parts of the Dominican Republic, baseball is it. San Pedro is poor but there are poorer parts. The southwestern corner is desert – it’s really poor, and at least in San Pedro you can produce food easily, you can have your own garden. They’re starting to produce baseball players too in places like Barahona and Azua.

That’s what baseball is in the Dominican Republic – a way to be saved. If you have a son who can play baseball, if he can get a good signing bonus, $100,000 or so, that will change the life of an entire family. If he goes on to make it in the Major Leagues, the average salary is $3 million a year. Only about three percent of players who are signed get there, but it’s certainly worth the shot. So this is very serious stuff. When you watch kids playing in San Pedro, they don’t look like they’re playing. They’re very serious about it. I always found it funny that there are a lot of baseball players around in San Pedro, and they’re easy to recognize because they tend to be larger than other people. They’ve been American fed. They’re athletic and speak some English, usually. Now I’m a fairly large guy who speaks English, so people in San Pedro would ask me if I ever played baseball. When I would say, yes, I did, like all American kids, the next question is where did you sign, what team did you sign for? That’s why you play. It’s not to get together with your friends and have fun. It’s a serious commercial activity that you start on when you’re two or three years old. That’s why they produce so many good baseball players. They know the game the way Americans used to know the game, but don’t so much anymore. When I was a kid – I grew up in the 1950s – all the kids played baseball and it was the sport, and everything else was unimportant. San Pedro reminds me of that.

Q. What is the economy like today? Is sugar still a major part of it, and where does baseball fit in?

A. The sugar industry is just a shadow of itself. There are still a few mills – three, basically. There is much smaller production than there used to be. The industry in general is way down, people don’t eat as much sugar as they used to. When the boom came in the 19th century, the working class was discovering sugar. There was this tremendous demand. Now people are trying to eat less sugar, and the bad sugar, like Coca Cola, isn’t made from sugar cane anymore. And that’s how most kids get their sugar – from soft drinks, from corn syrup. It’s a very depressed industry.

The port in San Pedro, which used to be a major commercial port, has very little activity. What the city does have, that it didn’t used to have, is tourism. There are nice resorts outside of town on the beach, and there is a very large duty free zone, where companies can bring in components duty free, have them assembled there and shipped out, and pay very low salaries. There is a small amount of foreign investment. Cemex – a huge Mexican cement company – has a plant there, which pollutes the water and is killing the fishing industry. There are a few large chain stores. One of the big economic activities is actually motor scooters that serve as taxis – you get a few pesos to give somebody a ride on the back. There is a university there, with a medical school – a lot of Americans go there because it’s cheap and you can get in. but even though its cheap, it’s more money than most Dominican families have.

There aren’t a lot of good options. None of this earns very much money. And sometimes in the Caribbean it seems like no matter what you do, you end up losing. Baseball is far and away the best option, even if you only have a three percent chance of making it, it’s worth the shot. If you imagine living in a family that has very meager housing and a very poor diet, and can’t afford medicine, and there’s an occupation that pays an average of $3 million a year, wouldn’t you work on your swing?

Q. How are relations between the U.S. and the Dominican Republic, and how has baseball influenced them?

A. They’ve always been complicated. Most Americans don’t know this, but there was a movement in the Dominican Republic to try to get annexed when Ulysses Grant was president. Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner led the fight to stop the annexation, and is today kind of a hero in the Dominican Republic, but obviously wasn’t at the time. Relations between the U.S. and the Dominican Republic have been very strongly shaped by two invasions and occupations, one at the time of World War I and the other under Lyndon Johnson in the 1960s.

On the other hand, people have relatives in the U.S., and the U.S. is the source of baseball. It’s a complicated relationship. Dominican culture is very different from American culture. When San Pedro kids get to the U.S. to play baseball, they find it very difficult to adjust, and have all sorts of great stories about their struggles in America, especially some of the earlier players. They want to be Dominican, not American. It’s not really their dream to immigrate to the U.S. It is their dream to play baseball and come back very rich. But of course a lot who are released from their teams in the U.S. never go back to the Dominican Republic, even though they’re not legal in the U.S. if they come over to play baseball, they have legal status as a migrant worker. They lose the job, they have no status. But even as illegal aliens they feel they have more opportunities than they would in San Pedro. And nobody likes to come home a failure.

Q. Did Dominican players change the way Americans thought about race, whether in baseball or more broadly?

A. Originally, it’s a confusing thing for Dominicans. Their notion of black and our notion of black are completely different. Most of the Dominican population is not considered black in the Dominican Republic – the overwhelming majority are mixed, which is not black for them, but is black in the U.S. According to Americans, 85% of the Dominican population is black. The Dominican Republic is in some ways a very racist place, but it’s a different racism than American. It comes as quite a shock to a lot of these mixed, light-skinned Dominicans that they are treated as black in the U.S., especially in earlier years, when they were included in Jim Crow in the South. Dominicans were playing baseball for many years without the Major Leagues being available because they were considered black. A lot of the great players of the Negro League, which was Major League quality baseball, played in the Dominican Republic, like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, but they couldn’t play in the U.S. until after 1946.

The first Dominican to play in the Majors was a guy known as Ozzie Virgil. I went back and looked at the press clips from early in his career, and it was barely mentioned that he was Dominican, but it was constantly mentioned that he was black. There was a big fuss made of his race, but people barely noticed his nationality. This was very perplexing to Dominicans.

Q. How do Americans regard Dominican players today?

A. One of the things that surprised me in working on this book was some of the reactions I received. When I first started working on it, I did a cover story for Parade about San Pedro. It got over 100 letters, most of them denouncing Dominican players and saying that there are too many foreigners in baseball. It never occurred to me that there would be such a sentiment, though, America being what it is I might have predicted it. You run into it all the time, you see it in press coverage. There’s tremendous interest in steroid use among Dominican players, as if this were a particularly Dominican thing, when in fact they were just imitating what goes on in the U.S. At this point, Major League Baseball has sent a special investigator to monitor the steroid scandals. They’re under this scrutiny that American players aren’t under.

There’s also the age scandal, because quite a few Dominican players lie about their age, and scouts have encouraged them to do so. This is seen in the U.S. as an attempt to exploit child labor – you’re not supposed to sign until you’re 16-and-a-half. A great deal of this lying about age is in the reverse, though. Nineteen and 20-years-old are saying they’re 16-and-a-half, which makes them worth more at signing.

I see a lot of prejudice against Dominican players in the scrutiny over these scandals, particularly as opposed to Cuban players. Cuban players are forced to defect if they want to play baseball, and Americans like that story. If Cubans could do what Dominicans can do – come over and play and go back in the winter – they probably would, and then Americans would have the same attitude towards Cuban players.

*Photo courtesy williamhartz.

Send A Letter To the Editors