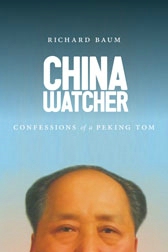

China Watcher: Confessions of a Peking Tom

by Richard Baum

–Reviewed by Angilee Shah

Looking back on China’s dramatic recent history, from the devastation of the Great Leap Forward to today’s exuberant “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” is a fascinating exercise. China Watcher offers the rare opportunity to learn this history as author Richard Baum did – from the front row.

Looking back on China’s dramatic recent history, from the devastation of the Great Leap Forward to today’s exuberant “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” is a fascinating exercise. China Watcher offers the rare opportunity to learn this history as author Richard Baum did – from the front row.

China Watcher is a memoir and a contemporary history rolled into one. A professor of political science at UCLA, Baum is a self-proclaimed China addict. “For more than forty years China has been my drug of choice,” he begins his narrative of “more than three dozen trips to China” to almost every province.

Baum began his academic career at a time when virulent anti-communism and the Free Speech Movement collided with leftist academic admiration for the Cultural Revolution, and when China was still closed to foreigners. Baum spent a year researching in Taiwan, where he recalls accidentally spending his first night abroad with his wife and infant son in a hotel frequented by prostitutes and their clients. Baum is forthcoming about his own cultural education, stumbling with language and bureaucracy – or, as he calls it, “China’s Great Wall of Inconvenience.” And he took the country’s tensions in stride, writing limericks about Mao’s notorious wife and the shortcomings of a colleague’s television appearance, and recognizing his own imperfections. “Over the years,” Baum explains,” I have generally prided myself on not taking myself – or my career – so seriously that I couldn’t laugh at my own foibles.”

Being a smart-aleck got him in trouble in academic circles at times, but it has served his memoir well. It is rare to find a serious scholar who is able to write about his life’s work with such levity. We witness not just his knowledge (and ours) about China grow, but also watch him coming of age. These are the strongest chapters, full of political missteps and scholarly achievement – sometimes both in one, as when he illegally copied a classified document outlining Mao’s socialist education program, which helped him analyze the Party’s secret directives.

The violent end of student and worker protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989 represent a turning point in history and in Baum’s narrative. The second half of China Watcher focuses more on China’s growth – its relationships with American universities and Baum’s own experience building exchanges included – and on the author’s cultural observations and political assessments, leaving behind the wonderfully vulnerable and personally revealing tone of earlier chapters. Baum believed that the Chinese Communist Party would have to do much to repair the wounds they inflicted in 1989, but “Reform and Opening” re-awakened a nationalism among Chinese students that he could not have predicted. By the late 1990s, alongside China’s growing economy and pride came rifts in U.S.-China relations and a spate of American books warning against China’s rise.

Baum does much to counteract China hysterics; he argues that China’s politics and society are becoming more open, along with its economy. He also holds that China’s leaders are insecure about the potential for uprisings: “The long, dark shadow of post-Tiananmen stress disorder lingers in China, casting a pall over the country’s political life,” he writes. His measured optimism for the country and its relations with the rest of the world are all the more convincing for his exciting narrative about a long career of China watching.

Excerpt: “Up close, the Chinese people seemed so…normal. With some surprise, I noted the ordinariness of their appearance, their clothes, and their mannerisms. What do they talk about at dinner? I wondered. How do they react when they see an American? Feeling conspicuous and self-conscious, I was oblique and indirect in my gaze, reluctant to initiate eye contact. The objects of my attention were not nearly so discreet, however. They stared right at me, boldly, without the slightest hint of shame or embarrassment.. On one occasion a passing bicyclist stared at me so intently he crashed into a light post. I found this combination of curiosity and brazenness off-putting at first, but endearing later on, as my Chinese friends and acquaintances exhibited no qualms whatever about grilling me as to the cost of my clothes, or the amount of my monthly income, or whether I had a Chinese girlfriend. I recalled from my Berkeley language training that the concept of privacy was not translatable into Chinese. One Chinese dictionary has defined it as ‘a Westerner’s liking for loneliness.’”

Further Reading: Red Star over China: The Classic Account of the Birth of Chinese Communism by Edgar R. Snow and Dilemmas of Victory: The Early Years of the People’s Republic of China edited by Jeremy Brown and Paul G. Pickowicz

Angilee Shah is a freelance journalist who writes about globalization and politics. You can read more of her work at www.angileeshah.com.

*Photo above courtesy yuan2003.

Send A Letter To the Editors