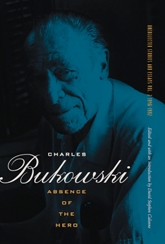

Charles Bukowski lived and wrote all over Los Angeles. He devoted a short piece, a June 1974 installment of his “Notes of a Dirty Old Man” column in the L.A. Free Press, to the hunt for home. He recalls his moves from the famed (and recently landmarked) DeLongre Avenue court, to a house with a girlfriend, to a “modern apartment,” and finally to Hollywood and Western, where he felt “in love with the world again.” Below, the newspaper column in full, pulled from a new collection featuring his unpublished or long unseen work, Charles Bukowski: Absence of the Hero, edited by David Stephen Calonne.

To find the proper place to write, that’s most important; the rent should be reasonable, the walls thick, the landlord indifferent, and the tenants depraved, penurious, alcoholic, and lower middle-class. With the advent of the high-rise apartments, small courts, with their own private entranceways, have more and more vanished, and the wonderful characters that once infested these places have vanished along with them.

I lived for eight years on a front court on DeLongpre Avenue, and the poetry and the stories flourished. I’d sit at the front window typing, peering through excessive brush onto the street; I’d be surrounded by beer bottles and listening to classical music on the radio, sitting in my shorts, barefooted, my fat beer belly dangling. I was surrounded by rays and shadows and sounds, and I made sounds.

My landlord was a drunk, my landlady was a drunk, they’d come down and get me at night…. “Stop that silly typing, you son of a bitch, come on down and get drunk.” And I’d go. The beer was free, the cigarettes were free, they fed me; they liked me, we talked until 3 or 4 in the morning. The next day they’d knock on the door and leave a bag of something: tomatoes or pears or apples or oranges, mostly it was tomatoes. Or often she’d come with a warm meal – beef stew with biscuits and green onions; fried chicken with gravy and mashed potatoes, and bean salad with cornbread. They’d knock, listen for my voice, then run off. He was 60, she was 58. I put out their garbage cans every Wednesday, eight or 10 cans gathered from the courts and the apartments in back. The alcoholic next to me fell out of bed at 4 each morning; there was an ATD case in one of the apartments in back; 14 Puerto Ricans lived in one of the center courts, men, women, and children, they never made a sound and slept on the rug next to each other.

My landlord was a drunk, my landlady was a drunk, they’d come down and get me at night…. “Stop that silly typing, you son of a bitch, come on down and get drunk.” And I’d go. The beer was free, the cigarettes were free, they fed me; they liked me, we talked until 3 or 4 in the morning. The next day they’d knock on the door and leave a bag of something: tomatoes or pears or apples or oranges, mostly it was tomatoes. Or often she’d come with a warm meal – beef stew with biscuits and green onions; fried chicken with gravy and mashed potatoes, and bean salad with cornbread. They’d knock, listen for my voice, then run off. He was 60, she was 58. I put out their garbage cans every Wednesday, eight or 10 cans gathered from the courts and the apartments in back. The alcoholic next to me fell out of bed at 4 each morning; there was an ATD case in one of the apartments in back; 14 Puerto Ricans lived in one of the center courts, men, women, and children, they never made a sound and slept on the rug next to each other.

Mad people came to visit me – Nazis, anarchists, painters, musicians, fools, geniuses, and bad writers. They all imparted their ideas to me thinking that I would understand. Some nights I would look around and there would be from eight to 14 people sitting about the rug, and I only knew two or three of them. Sometimes I would go into a rage and throw them all out; other times I just forgot it all. Nobody ever stole from me except one who professed to be my friend and was always fingering my bookcase, slipping first editions and rare items under his shirt. The police raided continually but only took me in once or twice, yes, it was twice. Once they came bearing a shotgun, but I told them I was a writer and they left. Yes, it was a good place to live and to write.

Then love came and I moved out and into this house with this lady. She was good to me and it worked well, I liked her two children; there was space and shadow, a crazy dog, and a large backyard, a jungle of a backyard with bamboo and squirrels and walnut trees, wild rosebushes, fig trees, lush plants. I wrote well there – many love poems and love stories; I had not written too many of those. I walked about and it felt as if the sun was inside of me; I was finally warm, and things seemed humorous, gleeful, easy; I felt no guilt about my feelings. Yet, that finally went bad as those things do go bad. One or both begin to build resentments; things that once seemed so marvelous no longer seem that way. Each blames the other – it’s you….you did this, you said that, you shouldn’t have acted that way, you….

I had to move quickly. I searched the streets for a plausible place, somewhere a man might possibly get off a short poem. The afternoons and mornings mingled: First and last month’s rent, $200 security, $75 cleaning, references. None of the places even seemed livable, and the landlords and managers gave off the worst of vibes: greedy, suspicious, dead-meat creatures. One of them wouldn’t even look at me; he just kept staring at his TV set and tolling off the charges. I began to feel dirtied, like an imbecile, a man without a right to hot and cold water and a toilet to rent as his own. There was actually no place to be found. In weariness I simply paid somebody and began moving in.

It was a modern apartment, a place in the back, up one flight, apartment 24. There was a garden in the center and two managers, man and wife, who lived downstairs and they never left the premises; one of them was always there, especially the lady, who dressed in white and walked around with a little brown bag and often caught the leaves as they fell from the bushes; she got them before they hit the ground. She was immaculate, face heavy with white powder; she wore much lipstick and had a rasping voice, a voice that always gave the sound of somebody lying. Her husband had the booming voice, and he boomed about the Dodgers and about God and about the prices in the supermarket. My first night there the phone rang and he told me that my radio was on too loud; they could hear me all over the court. “We can hear you all over the court, Hank,” he said. He insisted that we call each other by our first names. My radio had not been on loud. I turned it off. Then somebody started playing an accordion. “Oh, that’s beautiful!” I heard a voice. The guy ran through all the Lawrence Welk tunes.

She was always there, ubiquitous, most ubiquitous, and I’d have a hangover, be coming down the stairs, listening, thinking, she’s not around, I’ve gotten by her this time. And I’d have my bag of empties full of ashes and crap, the bottom wet and wanting to rip open, myself feeling like vomiting, I’d get down on the ground and then go through an opening in the back garage in between the cars, trying to get to the trash container, and out she’d pop with her broom: “It’s a nice day, isn’t it?” “Oh yes,” I’d say, “it’s a nice day.”

And she was always at the mailboxes when the mail came, she was out there with her broom; you couldn’t get your mail. Or if somebody unknown came to the court she’d ask: “What do you want?” On warm days she placed herself in one of the deck chairs and reclined, and it seemed as if all the days I lived there were warm. And others came out and joined her and one was allowed to listen to their voices and their ideas.

The modern apartment-dwellers are all the same; they spend much time scrubbing and waxing and dusting and vacuuming; everything glistens – stoves, refrigerators, tables; the dishes are washed immediately after eating; the water in the toilet is blue; towels are used only once; doors are left open, blinds parted, and under the lamps you can see them sitting quietly reading a safe paperback or watching a laugh-track family-affair comedy on a huge TV screen. They buy knickknacks and ferns, things to hang about, fill the spaces; a Sunday afternoon at Akron is their Nirvana. They have no children, no pets, and they get intoxicated twice a year, at Christmas and at New Year’s.

There were two small couches in my place about a foot and a half wide. Upon one of these I was supposed to sleep. It was impossible to make love to a woman on either one of them. I discovered 18 roaches behind the refrigerator, and whenever I typed the woman below me beat up on her ceiling with a broom handle. And there was always somebody knocking on my door saying that I was disturbing them. Then one day all the tenants were given forms saying that there would be an automatic $5-a-month boost for each apartment. The roach spray I used almost cost me that. The writing had dwindled, almost stopped. My editor phoned me and assured me that every writer had his slumps. He said that I had five years left; that I needn’t write anything for five years and that I still could make it. I thanked him….

And I lucked it. I found this court just off of Hollywood and Western; I found it by getting the inside that somebody was moving out before that somebody moved out. It is my kind of neighborhood – massage parlors and love parlors are everywhere; taco stands, pizza parlors, sandwich shops; cut-rate drugstores full of wigs and old combs, rotting soap, hair pins, and lotions; whores night and day; black pimps in broad hats with their razor-sharp noses; plainclothes cops shaking down people at high noon, checking their arms for needle marks; dirty bookstores, murder, shakedowns, dope. I walk up Western Avenue toward Hollywood Boulevard and the sun shines inside of me again. I almost feel in love again, My people, my time, the taste of it….

I’ve only been here a week and just last night I looked around, beer bottles were everywhere, the radio was on, and in my place there were some people who live in this court: a guy who runs one of the love parlors, two guys who work in a dirty bookstore, and a dancer from one of the bars. We talked about dildoes, shakedowns, some of the ladies of the boulevard and the avenue; we talked about the freaks and the good people and the hard-hearted; we talked all through the night, the smoke curling, the laughter O.K. We ran out of beer and the delivery boy came in high and screwed-up and stayed an hour. We sent out for chicken and potatoes and cole slaw and buns. The night rolled easy. Finally I called an end: I’d been drinking beer since 11 a.m. They left in good form. I went to the bathroom, pissed, and then went to bed. Hemingway couldn’t ask for better. The light was coming through; I was in love with the world again. Ah.

Copyright 2010 by the Estate of Charles Bukowski. Reprinted from the new collection Absence of the Hero: Uncollected Stories and Essays Vol. 2 1946-1992, Edited and with an introduction by David Calonne, by permission of City Lights Books.

*Photo courtesy revrev Homepage photo courtesy Roger Jones.

Send A Letter To the Editors