Gamers who spend hundreds of hours online in virtual worlds might seem strange to many of us, but they are gaining a sense of meaning and fulfillment that’s all too lacking in the real world. Game designer Jane McGonigal, who visits Zócalo on February 9th, argues in the excerpt below that in the virtual games we play are the tools to make reality better.

Gamers have had enough of reality.

They are abandoning it in droves–a few hours here, an entire weekend there, sometimes every spare minute of every day for stretches at a time–in favor of simulated environments and online games. Maybe you are one of these gamers. If not, then you definitely know some of them.

Who are they? They are the nine-to-fivers who come home and apply all of the smarts and talents that are underutilized at work to plan and coordinate complex raids and quests in massively multiplayer online games like Final Fantasy XI and the Lineage worlds.

They’re the World of Warcraft fans who are so intent on mastering the challenges of their favorite game that, collectively, they’ve written a quarter of a million wiki articles on the WoWWiki-creating the single largest wiki after Wikipedia.

They’re the United States troops stationed overseas who dedicate so many hours a week to burnishing their Halo 3 in-game service record that earning virtual combat medals is widely known as the most popular activity for off-duty soldiers.

They’re the young adults in China who have spent so much play-money, or “QQ coins,” on magical swords and other powerful game objects that the People’s Bank of China intervened to prevent the devaluation of the Yuan, China’s real-world currency.

Most of all, they’re the kids and teenagers worldwide who would rather spend hours in front of just about any computer game or video game than do anything else.

These gamers aren’t rejecting reality entirely. They have jobs, goals, schoolwork, families, commitments, and real lives that they care about. But as they devote more and more of their free time to game worlds, the real world increasingly feels like it’s missing something.

Gamers want to know: Where, in the real world, is that gamer sense of being fully alive, focused, and engaged in every moment? Where is the gamer feeling of power, heroic purpose, and community? Where are the bursts of exhilarating and creative game accomplishment? Where is the heart-expanding thrill of success and team victory? While gamers may experience these pleasures occasionally in their real lives, they experience them almost constantly when they’re playing their favorite games.

The real world just doesn’t offer these things up as easily. Reality isn’t engineered to maximize our potential. Reality wasn’t designed from the bottom up to make us happy. And so, there is a growing perception in the gaming community: Reality, compared to games, is broken.

But what if we decided to use everything we know about game design to fix what’s wrong with reality? What if we started to live our real lives like gamers, lead our real businesses and communities like game designers, and think about solving real-world problems like computer and video game theorists?

I’ve been designing games professionally for the past decade. And I’ve come to believe that people who know how to make games need to start focusing on the task of making real life better for as many people as possible.

Back in 2001, I was a “starving” graduate student-earning a PhD in performance studies from the University of California at Berkeley. I was the first in my department to study computer and video games, and I was particularly interested in how games could change the way we think and act in everyday life-a question that, back then, few, if any, researchers were looking at.

Eventually, I published several academic papers (and a five-hundred-page dissertation) proposing how we could leverage the power of games to reinvent everything from government, health care, and education to traditional media, marketing, and entrepreneurship-even world peace. Increasingly, I found myself called on to help large companies and organizations adopt game design as an innovation strategy-from the World Bank, the American Heart Association, the National Academy of Sciences, and the U.S. Department of Defense to McDonald’s, Intel, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and the International Olympic Committee.

Some twenty-five hundred years ago, the Greek historian Herodotus saw the early games played by the Greeks as an explicit attempt to alleviate suffering. Today, I look forward and I see a future in which games are explicitly designed to improve quality of life, to prevent suffering, and to create real, widespread happiness. I see a future in which games continue to satisfy our hunger to be challenged and rewarded, to be creative and successful, to be social and part of something larger than ourselves.

If we take everything game developers have learned about optimizing human experience and organizing collaborative communities and apply it to real life, I foresee games that make us wake up in the morning and feel thrilled to start our day. I foresee games that reduce our stress at work and dramatically increase our career satisfaction. I foresee games that fix our educational systems. I foresee games that tackle global-scale problems like climate change and poverty. In short, I foresee games that augment our most essential human capabilities-to be happy, resilient, creative-and empower us to change the world in meaningful ways.

Let the games begin.

Excerpted from Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World, by Jane McGonigal. Copyright © 2011 by Jane McGonigal. Excerpted with permission by Penguin Press.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s, Amazon

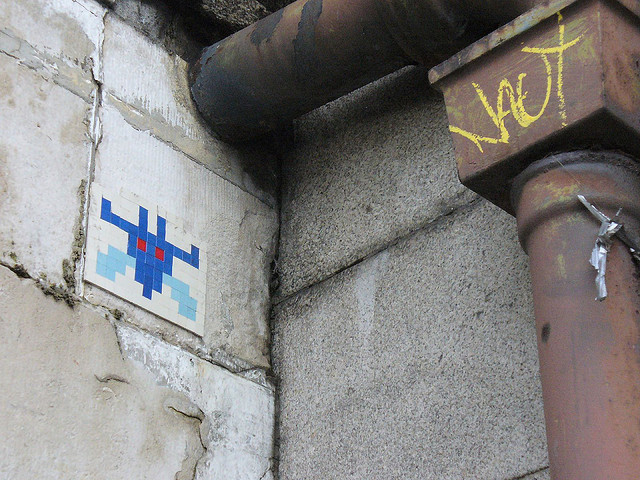

*Photo courtesy of brothermagneto.

Send A Letter To the Editors