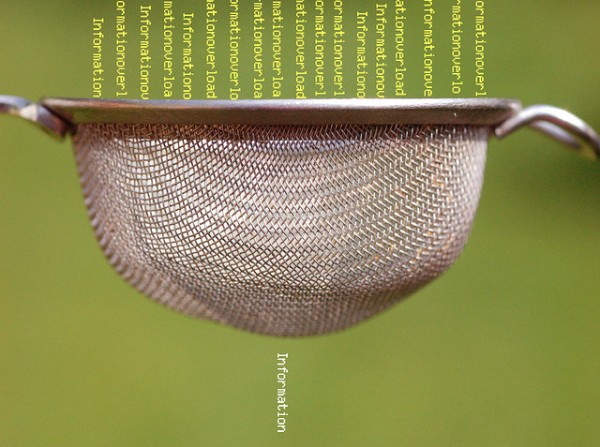

Information rules all of our lives. In fact, DNA, the building block of our bodies, is “the quintessential information molecule,” writes journalist James Gleick in his new book, The Information: A Theory, a History, a Flood. Yet all this information can be overwhelming and difficult to use effectively. In advance of Gleick’s appearance at Zócalo on March 15, we asked experts whether more information is always a good thing.

More is More: You Can’t Have TMI

Everything we know and will ever know is based on information. The amount of information created within our known physical world every second far exceeds our ability to collect and process it all. From all of these bits, words, thoughts and behavioral traces we recreate and interpret our histories. Some hope to predict our futures.

If anything there is too little information.

Everyone has an opinion, and opinions are a type of raw and dirty information–they are malleable ideas formed and packaged by the circumstances of our experiences. If you spend time on opinion forum websites such as Reddit.com you can find a virtual sea of opinions ranked and rated by others, forming an emergent hierarchy of insight, wit, poignancy, humor and absurdity (but certainly not in that order).

Focusing this information into something “meaningful” in a given context is very difficult. I believe that the problem of “too much information” is largely eclipsed by the problem of making sense of the information we have. In the time that I spent typing up this paragraph, millions upon millions of opinions were formed and shared with others around the world. A sizable number of these opinions were uploaded to the Internet in the form of emails, blogs, forum posts, tweets and status updates on social networking websites. For social scientists such as me, it is never enough information.

When we turn our attention to very precise problems, the dearth of information becomes clear. Like many of us, I was awestruck and deeply saddened by the devastation caused by the earthquake and tsunami in Japan on March 11. One interesting bright spot amid the human tragedy was that more information was captured about this earthquake than any other major earthquake of this size and scope in history. Those raw numbers and calculations about depth, shake, and tectonic movement are invaluable pieces of information for seismologists and geologists–and yet, still, it is never enough. If they just had a little more information about “where, what, when and why” they could address so many important scientific questions.

Is there really too much information? I would strongly argue no, but the complexity of this question is often wrapped in the equally challenging questions that it implies. Retrieving, storing, organizing, and processing information into usable knowledge are they key hurdles for addressing the big questions in life and in science.

Cheshire Coye is an Assistant Professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Information.

—————————————————————————————————————

All This Information is Great: Let’s Catch Up To It

“Can there be too much information?” Too much for what? For any one task? Sure, but, we should remember how hard it was fifteen years ago to get a simple question answered.

The real story–the one historians will tell–is that over a mere fifteen years, the world has collaborated to make openly available a trillion linked pages and the tools for navigating them, bringing about epochal changes in the nature of knowledge.

Back when paper was the primary medium of knowledge, we managed the fact that our skulls are way too small to know the world by filtering out most of what was submitted for publication and then filtering out of the libraries most of the books that were accepted. We thus had an illusory sense that there was a manageable amount of information.

With a new primary medium of knowledge–the Internet–we filter forward, not out. That is, we curate collections by posting links that bring sites within one click, but all the other sites are still there and visible. We not only are aware of their abundance; we also learn that we are never ever going to all agree about anything. Thus, knowledge is no longer made up the set authority-approved works that together build a consistent, universally-accepted picture of the world. Knowledge is more like a market in which truths are constantly negotiated.

There are dangers, of course. But the old reductive strategies for dealing with a world that is too big to know had their own drawbacks. Skulls don’t scale. Paper and libraries don’t scale. Networks scale. Knowledge now has a chance to catch up.

David Weinberger is senior researcher at Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society and is the author of several books on technology and ideas, including the forthcoming Too Big to Know.

—————————————————————————————————————

Sure, There’s Too Much Information. Look Around.

Yes, there’s definitely such a thing as too much information. In a study back in 1997, we found that users performed 58 percent better when a website cut its word count in half. Writing less means that people get more from your content. What matters is not the number of words you produce, but how much impact they have.

What can we do about the profusion of info on the Web? Two things:

• Fight information pollution. Just because you can write something doesn’t give you the right to pollute cyberspace with ever-more information. Cut the words. Edit. (Bulleted lists and highlighted keywords are always good). Learn strategies for managing information overload. From now on, there will always be too much info, so you have to develop coping strategies. Unfortunately, very few people currently have the skills to navigate the Web in a masterful way: In one of our recent studies, users only changed search strategies one percent of the time. People fall prey to whatever is put into the top few positions by the search engine–a phenomenon I call Google Gullibility.

• Change the the way we teach computer skills in school. We must emphasize deeper skills that will make students masters of the information world instead of victims. Sadly, our studies of how children use websites show that the next generation has weak research skills and little true mastery of the online domain. Long-term change must start in the schools and must equip users with the ability to survive ever-wilder information tsunamis.

Jakob Nielsen is principal of Nielsen Norman Group, a research company studying how people use computers and the Internet. His latest book is Eyetracking Web Usability.

—————————————————————————————————————

Nope. TMI Isn’t a Problem. Just Organize It Better.

I’ll give you the short answer first: no. Then I’ll explain.

To begin with, we cannot wish information away. Once you start adding, taking away is difficult. In Everything is miscellaneous, David Weinberger wrote that this is in the nature of things: while objects in the physical world have limitations due to their weight, mass, size, we can have as much information we want attached to anything living in information space. Size does not matter.

And it’s getting worse, as information bleeds out of computers and into all kinds of connected devices. Because this is the second point: not only digital information can be stored very efficiently, but to make it more valuable it can be connected. And if the Web has taught us any lesson, it’s that once you start connecting, complexity emerges, and things happen we did not foresee.

An example: since we have photos on Flickr, someone came up with the idea that we could use them to build 3-D photo-realistic reconstructions of places. Good. But these reconstructions are new information artifacts themselves, and call in for more information, either system- or user-generated, to be used efficiently. Information is not going away easily.

For me the issue then becomes one of understanding how these dynamic information spaces, what we call pervasive information architectures, can still be of any use, how we can avoid what R. S. Wurman calls information anxiety. I think the solution is quality over quantity.

Let me try to explain with another example. There’s this short by Pixar, Lifted. Some presumably young alien in a spaceship hovering outside a house is going through training: he (she?) has to abduct a sleeping man from his bed. The problem? She (hrmpf) keeps banging the poor guy all over the room: the control dashboard sports a thousand switches, and they are all the same.

And here’s the problem: not information overload per se, but any unnecessary overload. Contextual, meaningful, necessary information is never the issue. Why do all the switches have to be there and look the same? Why do we have to go through a thousand similar choices? It’s an overall issue of quality in the way we information architects and user experience designers organize, visualize, and present information. The solution is simply better design.

Andrea Resmini is a researcher at the University of Borås, Sweden, and an information architect with FatDUX, a UX firm with headquarters in Copenhagen. An ICT professional since 1989 and a practicing information architect since 1999, Andrea holds a PhD in Legal Informatics and a MA in Architecture and Industrial Design. He co-founded the Journal of Information Architecture and currently acts as President of the Information Architecture Institute. His book Pervasive Information Architecture (written with Luca Rosati) is due April 2011.

—————————————————————————————————————

Sure, There’s Too Much Information. But Edward Gibbon Had the Same Complaint.

When it comes to assessing the matter of “Too Much Information,” I’ll ignore examples such as breeches of privacy, because I lack that specific expertise. Instead, I’ll look at whether one can have too much information of the kind that its producers mean to share openly. Clearly there are frustrations and costs associated with the accumulation of information–including the resources expended to store and manage information, to find what you’re looking for, or the opportunities missed when the good stuff is swamped by the useless or the bad. But these problems are hardly new.

Articulations of the feeling of overload can be found in antiquity and the middle ages and became especially common once printing made it possible for more people to have access to more books than any one person could actually read. In the 18th century some thinkers felt so strongly about the problem that they fantasized about a radical solution–destroying books: Edward Gibbon for example recommended destroying “the ponderous mass of Arian and Monophysite [theological] controversy” and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert what he called “useless historical works.” At the same time professionals of information management in the early modern period, such as authors of reference books, were also conscious that what one person considered useless another might value highly.

As a historian I am especially mindful of the utility to historians of the refuse of another era and I worry about digital technologies hampering our ability to look back at materials that have not been kept current and are preserved only in obsolete hardware and software. But as digital information continues to escalate, we will also clearly need continuously to devote resources and ingenuity to devising methods of management (of filtering and searching, to use Gleick’s terms) to find our way to what we seek, each for our own purposes, and keeping in mind that we will have purposes in the future that we are not yet aware of.

Ann Blair is the Henry Charles Lea Professor of History at Harvard University and author of the forthcoming Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age.

*Photo courtesy of verbeeldingskr8.