Before distance running entered the mainstream culture in the 1970s, before marathons and road races attracted thousands of runners, before Nike and Reebok, there was a distance running subculture in Southern California.

You wouldn’t have known it existed from the Los Angeles Times or local television and radio. But a vibrant distance running community emerged in the 1960s. This community was linked by a network of all-comers races, weekly road races and newly established marathons. Most importantly, new attitudes were emerging among these runners: about long distance running as a lifestyle, as well as about workout regimens, diet, lifelong training and the inclusion of women.

My older brother Jim, then a senior at Fairfax High, introduced me to long distance running in the summer of 1967, a few months before I was to start my freshman year. My first run was from our house in the Fairfax district to the top of Mt. Olympus in the Hollywood Hills. Though I ran only the first two miles and walked the rest, I was hooked.

Fairfax did not have a strong tradition of long distance and track athletes. According to Gabe Grosz’s history of Fairfax track, the school lost every track meet between 1962 and 1965. But all that changed in the fall of 1967 with the arrival of a new coach, John Kampmann.

Like other successful high school coaches, Kampmann brought a commitment and passion to the sport that was contagious. Running was not done part-time or occasionally; it was a daily, year-round regimen. Running was one part physical, and a larger part mental. Running was linked to diet, sleep and focus.

Long distance training under Coach Kampmann was a mix of approaches: speed-play techniques from Finland, repetitions on the track, and long slow distance (LSD). We ran in the Hollywood Hills, on the trails of Griffith Park, at the La Brea Tar Pits near Fairfax. We ran at the area’s golf courses, throughout Brentwood and UCLA, at the Santa Monica beach. On weekends, we ran through the canyons north of Sunset. We’d start at Burton Way and La Cienega and each week choose a different canyon: Franklin Canyon, Coldwater Canyon, Benedict Canyon, Beverly Glen Drive – 12, 14, 16 miles. Often on Sundays, we’d do a canyon run in the morning and come back at night with a three- or four-mile run at the Los Angeles Country Club.

By the next year, Fairfax was among the top cross country and track teams in the city. In the spring of 1968, Mike Wittlin set a city record with a two-mile time of 9:17. The following year, Dan Schechter won the city mile championship with a time of 4:16. In dual meets, the half-mile squad, led by Gary Shapiro, regularly ran in the 1:50s. Fairfax lost only one dual track meet in 1969. During the next two years, Fairfax won 14 straight dual meets.

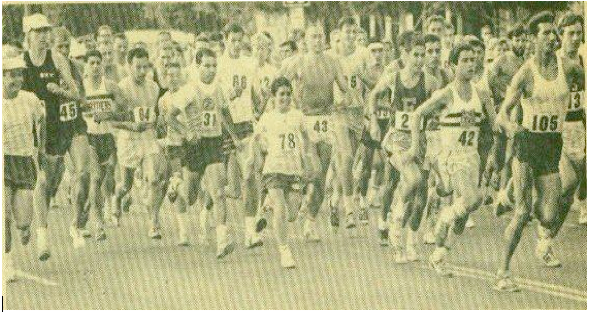

Beyond competing as a team, we were part of the region’s distance community. We traveled throughout the region on weekends to compete in road races in Montebello, Pacific Palisades, Diamond Bar, Toms Peak and the Los Angeles Police Academy. We ran the Culver City Marathon in 1967 and 1968, and the Palos Verdes Marathon in 1969 and 1970. We traveled in a van to San Diego to run the Mission Bay Marathon in January 1970. During the summer, we competed in the all-comers meets at Venice High, Pierce College and Los Angeles Community College.

The region’s distance community was not large. Each road race might have 100 runners, and even the marathon races rarely had more than 200 or 300. The runners, though, traveled to the same races, met at the same handful of stores that sold running shoes and read the same books and articles on running, particularly the running bible, Track and Field News. Through these interactions, the running subculture grew.

Mainstream athletic culture in 1960s Southern California focused on a few team sports, primarily baseball, football, and basketball, in which a small number of athletes actually competed. Most high school athletes and non-athletes did not continue active exercise after graduation. But in distance running, everyone trained and competed. A main part of the sport involved reaching “PRs” (personal records), pushing yourself to improve your own time. Coach Kampmann gave as much attention to each runner’s personal record, from the slowest to the fastest runner, as to the team score.

Running did not stop in high school. It is a lifelong pursuit. At the road races, you’d see runners of all ages, and from a wide range of occupations. Further, the groundwork was being laid for the establishment of women’s high school and college teams, and for the full participation of women in all distance races.

Most of us from that running era at Fairfax have continued to find value in the distance running culture and continue to run daily. My own running career would have its ups and downs over the years. On a Saturday morning in May 1970, I ran my second Palo Verdes Marathon, finishing in 2 hours, 42 minutes – among the top 20 high school marathon times in the United States that year. Later that year, I went east to Harvard, where I joined the cross-country and track teams. My participation, though, ended after two mediocre years. A few years later, I competed again as a graduate student at Oxford University in England (where graduate students could compete on university teams), but stopped after an undistinguished year. In both cases, running had lost its cultural ties: the sense of purpose, the broader lifestyle, the camaraderie.

Since returning to California in 1976, I’ve continued to train, almost exclusively long slow distance, increasing my weekly miles over the past 10 years. Today, I run twice a day, around 40- 50 miles per week. If you’re on the Presidio roads and trails in San Francisco, you’ll see me at 6 a.m. and 8 p.m., usually with a Nike hat and a hiker’s light, running at a nine-minute-mile pace, alone and in thought.

Similarly, if you look around the streets of Southern California, you’ll see others from the 1960s Fairfax teams who continue distance running: Gary Shapiro, Eli Kantor, Jeff Rothman, Bobby Sherman, Mike Wittlin, Irwin Merein, Roy Cohen, Tom Flesch, Dale Lowenstein, Sam Kiwas.

But the full legacy of those Fairfax years stretches far beyond our teams. Long-distance running has soared in popularity, and today attracts thousands of runners, both men and women, to major races. Thanks to the coaching and life philosophy of John Kampmann and other Southern California running advocates of the 1960s, for many of us reminiscing about high school sports isn’t an exercise in remembering things long gone, but rather reflecting on the birth of ongoing life-affirming habits.

Michael Bernick, an attorney in San Francisco, has served in several government positions in California, including director of the state labor department, the Employment Development Department, 1999-2004, and director of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART), 1988-1996.

*Main photo originally published in Track and Field News, May 1969

**Photos courtesy of Michael Bernick.

Send A Letter To the Editors