In Squaring Off, Zócalo invites authors into the public square to answer five questions about the essence of their books. For this round, we pose questions to Ben Berger, author of Attention Deficit Democracy: The Paradox of Civic Engagement.

Since the birth of democracy, governments have struggled against the political apathy of their constituents. But Swarthmore political scientist Berger makes the case that it’s neither realistic nor helpful to expect citizens to devote more time and energy to politics.

1) Is it counter-intuitive for you to argue that citizens have a limited attention span for participating in democracy-but that we should foster not just “civic engagement” but three separate forms of engagement: political, moral, and social? Isn’t that a lot more time and work?

When I write about “engagement” I simply mean a combination of attention and energy-in other words, focus and follow-through. I suggest axing the term “civic engagement” because it’s become so popular that it means something different to everyone; we wind up talking past each other. Replace it with its constituent parts: social, moral, and political engagement. Those categories describe some of the ways in which we already invest our attention and energy: on social dynamics, on moral principles and problems, on political institutions and outcomes. Which kinds of engagement matter most for making democracy work, and how can they be encouraged?

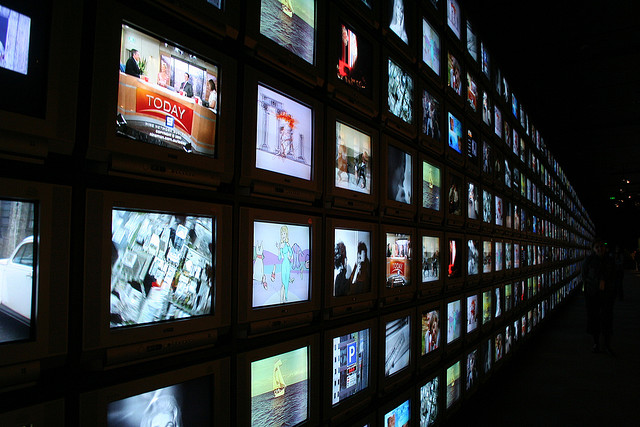

My book focuses on political engagement. I do argue that citizens have a limited attention span for politics, but only because we have a limited attention span for everything. It’s difficult to focus ourselves on one subject enduringly unless we love it. That’s why most people pay more attention to their hobbies, or their favorite television shows, than to politics. How worried should we be, and how can we do better?

Rather than trying to tax our already overburdened reserves of attention and energy, I suggest ways in which we can make more efficient use of those scarce resources toward the overall goal of improving American democracy.

2) When it comes to political engagement, you argue for quality over quantity-not that society invest more attention and energy, but that we better invest our existing attention and energy. But if it’s not simply numbers (i.e. voting rates), is it possible to objectively measure how politically engaged a society is?

You’re right to suggest that measurement is important; otherwise it would be hard to know whether we’re moving in the right direction or whether we’re even setting the right goals. But I wouldn’t characterize my argument as one of quality over quantity. In some cases the quantity of political engagement matters more than in others. Marginalized citizens, especially the poor and poorly educated, are the least likely to engage politically and the most likely to be represented poorly (by politicians and activists) when disengaged. If we care about democracy’s ideals of fairness and legitimacy we should work to increase political engagement among the marginalized.

To the extent that I de-emphasize the importance of quantity it’s to argue that if we were to reconfigure our political institutions we could achieve fairer, more inclusive and more satisfying democratic outcomes even if we didn’t invest much more attention and energy in politics. And because it costs a lot of money to increase political engagement, and might even require coercion-think of compulsory voting in countries such as Australia-we shouldn’t just assume that more political engagement is the answer to our problems. Democracy requires collective action to solve shared problems, but that collective action doesn’t have to be political.

3) You point out that democracy can thrive in countries with low levels of political engagement as long as moral and social engagement are high. Broadly, you’ve defined social engagement as “all manner of associational involvements … as well as informal socializing and personal friendships.” But what is moral engagement-and is it possible for a society to foster it?

This book focuses primarily on political engagement, but I’m working on a new book that examines moral engagement’s role in making democracy work.

Since engagement means a combination of attention and energy, moral engagement means attention to moral principles and then appropriate follow-through. It’s not truly moral engagement if you know the right principle but don’t act on it. It’s also not sufficient to do the right thing unthinkingly or by accident; that’s unreliable.

But moral engagement in general can’t guarantee morally desirable outcomes, either. Violent extremists tend to be morally engaged, although with illiberal and intolerant moral principles. My new book project tries to identify the kinds of moral engagement-engagement with liberal-democratic principles such as tolerance, law-abidingness, and trust-that liberal democracies can’t do without.

How can we foster the “right” kinds of moral engagement? The traditional answers apply: through our parenting relationships, our local communities, our religious and spiritual congregations, our schools and our laws. When I claim that a liberal democracy can flourish without extremely high levels of political engagement as long as it features high social and moral engagement, I’m describing a democracy with a strong civil society.

4) You argue that idealistic conceptions of participatory democracy don’t provide useful goals for political engagement. But if even the U.S. Constitution strives for “a more perfect union,” shouldn’t citizens aim higher?

Bill Galston once defined a public philosophy as a set of beliefs that “specify general directions for public policy within a basic understanding of how the world works.” I presented Attention Deficit Democracy as an accessible public philosophy: a diagnosis of the world that will actually resonate with most citizens, plus practical prescriptions that they’ll deem worthy and achievable.

I’m not down on idealism; I’m cautious about certain excessively idealistic theories of participatory democracy in particular, theories that make unsubstantiated diagnoses and unachievable prescriptions. It’s fine to lay some blame for our political inattention on capitalism, big government, and technology, as certain theories do, but democracy’s inattention goes back to ancient Greece and long predates the preceding influences. And it’s fine to love political engagement; enthusiastic participants can lead by example. But it’s downright undemocratic to assume that everyone else could or would share one’s tastes if only conditions were different. Some of us love political engagement, some hate it, and many want more meaningful political engagement than they have now but don’t want it all the time. Any theory that can’t address all three constituencies may be a philosophy, but it won’t be a public one.

5) What is in your view the most achievable, practical, and accessible prescription that can increase our society’s level of political engagement now?

I’ll give you one prescription for practical improvement now, one for the future, and one that won’t necessarily increase our quantitative engagement now or down the road but that should help us to economize on our limited attention and energy.

For immediate results, make politics more appealing. We pay attention to what we like; that includes entertainment. True, we don’t want to purchase popularity at the expense of tawdriness (OK, more tawdriness). But you asked about prescriptions that would increase political engagement right now. If you’re dismayed by the prospect of the American Presidency resembling American Idol, as I am, then encourage initiatives such as Rock the Vote that employ celebrities and popular music to grab people’s attention and turn it to political issues.

To promote greater long-term engagement we should encourage young people to develop more political tastes by revitalizing nonpartisan political education in our schools. Make it participatory and fun rather than traditional and boring. Once we’re out of school we get to make our own choices.

Finally, revitalize our political institutions-especially political parties. Parties used to be much more sociable, with local chapters comprised of neighbors who socialized continuously rather than once every four years. In other words, put the “party” back in political parties.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s, Amazon

*Photo courtesy of chelseajt.