As the state of Arizona turns 100, it finds itself greater in population than its earliest inhabitants could have imagined. Water, land, social cohesion, governance, turf–all of these have been subject to pressures from growth and changing demography. But where, if we look back at historic moments, do we find the ones that affect the state most today? In advance of the Zócalo event, “Does Arizona History Matter?“, in Tucson, we asked several Arizonans to reflect on how Arizona’s past is shaping its future.

You like Phoenix? Thank the taming of the Salt River.

Arizona history has included many milestones: the rich mineral strikes, the arrival of the railroads, the technology brought on by WWII and affordable air conditioning. But the one with the greatest impact on this land of little rainfall was the taming of the Salt River in central Arizona.

Arizona history has included many milestones: the rich mineral strikes, the arrival of the railroads, the technology brought on by WWII and affordable air conditioning. But the one with the greatest impact on this land of little rainfall was the taming of the Salt River in central Arizona.

The Salt River Valley was blessed with a 13,000 square-mile watershed. All the runoff from the central mountains eventually flows into the Salt River, which runs through the heart of the Valley.

With the passage of the National Reclamation Act in 1902, the federal government chose this area for the nation’s first reclamation project. A decade-long drought in the 1890s had caused many farmers to abandon their farms and leave the area. Things looked bleak as Arizona was in the homestretch of its rocky road to statehood, but with the completion of Theodore Roosevelt Dam in 1911 Arizona’s bright future was assured.

Over the next few years, several other dams were completed on the river. In 1950, Phoenix was the 95th-largest city in the nation, with a population of just over 100,000. Fifty years later, it had grown to almost 1.5 million and was America’s fifth-largest city.

Arizona’s a great place to live, work and play. The state is blessed with a mild, healthy climate, open spaces, natural beauty an abundance of natural resources, great institutions of higher learning ,and minimum danger of physical hazards such as earthquake, fires, tornadoes, or floods.

Why do they come? In a word, lifestyle. But none of this would have been possible had the capricious Salt River not been harnessed.

Marshall Trimble is a native Arizonan. He’s authored more than twenty books on the state and has taught Arizona history at Scottsdale Community College for 40 years. In 1997, he was appointed official state historian.

————————————-

You like Southern Arizona? Thank the Gadsden Purchase.

Most of the current state of Arizona–along with the rest of the Southwest–became part of the United States as a result of the treaty that ended the Mexican War (1846-1848), but its boundaries took their final form when a once-popular project to build a southern transcontinental railroad resulted in the Gadsden Purchase (1853). It involved the area of the Mesilla Valley that comprises 30,000 square miles of southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. The latter acquisition paled in comparison to the 750,000 square miles of the prized territories of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas, but while the railroad venture never materialized, the people of the Mesilla Valley would shape the history of Arizona for the next one hundred and fifty years.

Most of the current state of Arizona–along with the rest of the Southwest–became part of the United States as a result of the treaty that ended the Mexican War (1846-1848), but its boundaries took their final form when a once-popular project to build a southern transcontinental railroad resulted in the Gadsden Purchase (1853). It involved the area of the Mesilla Valley that comprises 30,000 square miles of southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. The latter acquisition paled in comparison to the 750,000 square miles of the prized territories of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas, but while the railroad venture never materialized, the people of the Mesilla Valley would shape the history of Arizona for the next one hundred and fifty years.

Ethno-demographically speaking, during the American period, southern Arizona has always been Mexican Arizona. Such was the presence of the Mexican population in the territorial years that Tucson was the capital from 1867 to 1877. It was in southern Arizona where the first white immigrants settled and almost universally married Mexican women. It was there where, unfortunately, whites and Mexicans at times united to attack Indian residents and Chinese miners. It was also there that mining companies enticed even more Mexicans to immigrate.

From the beginning, the old Mexican pueblos defined what Americans perceived as Arizona. As the Mexican population increased, it was there that congressional voices found the justification for denying Arizona statehood for five decades: the presence of “too many Mexicans.” It is currently there where one undocumented crosser dies every thirty-six hours in his or her pursuit of happiness. It is there, of course, where supporters of the recent anti-immigrant legislation have focused. It is there, one might surmise, where an anti-immigrant consensus would originate, but such is not the case.

Now, as during the last 150 years, the Mexican population in southern Arizona has counterbalanced the anti-Mexican sentiments that originated from central Arizona and from mining towns. Editorials during the 1800s frequently engaged in vitriolic denunciations of so-called Mexican crime waves and called for the expulsion of Mexicans from Arizona and even for the invasion of Mexico. Yet, Mexican and white residents in places like Tucson not only refrained from such attacks but actually called on others to halt their unfounded claims. It is there in the 21st century, in the area of the Gadsden Purchase, where not just Americans of Mexican ancestry, but also empathetic voices from various groups, have expressed a different opinion in the ballot box.

Just like the landscape of Arizona would be difficult to conceptualize without the Grand Canyon in the north, the history of its people would make little sense without the Mexican population that already lived in the south and the even larger numbers that have continuously immigrated.

Sal Acosta, professor of history at Fordham University, specializes in Mexican American history.

————————————-

You like the mix of cultures in Arizona? Thank, once again, the Gadsden Purchase.

The signal event in Arizona history, constitutive geographically and politically adventurous, was the acquisition from Mexico of what is now about a third of the state, the region informally known as Baja Arizona stretching from the current international border to the Gila River. It’s known as the Gadsden Purchase of 1854.

The signal event in Arizona history, constitutive geographically and politically adventurous, was the acquisition from Mexico of what is now about a third of the state, the region informally known as Baja Arizona stretching from the current international border to the Gila River. It’s known as the Gadsden Purchase of 1854.

By annexing southern Arizona–and thereby completing the state we know today–Arizona changed itself forever. On a relatively minor level, it made explicit a connection between Tucson and Mesilla/Las Cruces, New Mexico that still resonates in the deep mindfulness of southern Arizonans. One recalls that the old Placita in downtown Tucson (pretty much destroyed in urban renewal in the late 1960s) was known as Plaza de Mesilla, the western endpoint of a corridor between the two places. Even today, it is easy to stand in the plaza in Mesilla and think of Tucson, to feel that one is almost home. On a more significant level, the annexation of southern Arizona incorporated nationalities into formal union with the American identity. By moving the international border south, the United States, with a stroke of the pen, brought large populations of Tohono and Akimel O’odham and Mexicans forcibly into the American polity. This, more than any other historical event, set the stage for both our richest heritage and the struggles we are all too familiar with in our current politics.

Some of us seek to embrace our regional diversity; others are fearful and closed. The great symbol of the enlarged Arizona, the Arizona we recognize and celebrate today, is Mission San Xavier del Bac. That living relic of the eighteenth century and the “Rim of Christendom,” an O’odham parish church, has inscribed in its very architecture and decorative iconography pluralistic influences stretching from Arab Damascus to Mudejar Spain, Catholic New Spain and Mexico. In this still contested region at the periphery of empire, we continue the struggle to construct a meaningful and just identity. It is that which marks us. It is our legacy and our challenge.

Joseph Wilder is director of the Southwest Center at the University of Arizona.

————————————-

You like the irrigation canals? Thank the Hohokam.

Around two thousand years ago, a remarkable group of indigenous people in the Southwestern region of North America created one of the wonders of the ancient world. The people known today as the Hohokam, using only stone and wooden tools and their intimate knowledge of their desert lands, created a massive and complex irrigation system that made the Valley of the Sun (where present day Phoenix is located), into a breadbasket–or, in the case of the Hohokam, a bean, corn and squash basket.

Around two thousand years ago, a remarkable group of indigenous people in the Southwestern region of North America created one of the wonders of the ancient world. The people known today as the Hohokam, using only stone and wooden tools and their intimate knowledge of their desert lands, created a massive and complex irrigation system that made the Valley of the Sun (where present day Phoenix is located), into a breadbasket–or, in the case of the Hohokam, a bean, corn and squash basket.

The Hohokam dug and maintained more than 1,000 miles of canals and an elaborate watering schedule that diverted the life-giving waters of the Gila and Salt rivers into their fields. This farming system yielded an abundance of foods to sustain more than 30,000 people who called the Valley home. The Hohokam also grew cotton, known today as Pima cotton, one of the highest quality cottons in the world.

Cities sprang up along the canals, providing shelter from the harsh desert climate for families, employment for farmers, artists and students of the heavens, and the traders who came to do business with the Hohokam. Turquoise from New Mexico, shell jewelry crafted by California tribes, and pottery in the shape of Central American parrots now provide mute evidence to the trading that once took place among the ball courts, homes and businesses of the Hohokam cities.

However, times changed for this ingenious people. Long drought periods followed by seasons of massive flooding and salt buildup in the soil all contributed to a decline in farming and relocation away from their cities. Two major groups emerged from this exodus: the Akimel O’odham, or River People, and the Tohono O’odham, or Desert People. The Akimel O’odham gathered in smaller communities along the rivers and continued in their farming traditions. Their desert cousins moved south to the washes and mountains west of Tucson,ranging down to current Northern Sonora. The Tohono O’odham split their time between winter homes down in the desert and summer homes high in the cool mountains.

These O’odham people now live in four Arizona tribal communities and continue to engage in their ancient traditions of farming, pottery, basketry and cultural pursuits. It’s interesting to note that the Gila River Indian Community recently undertook a project to reopen farmlands after they regained their water rights. When surveying to determine where to put their canals, the community discovered that their ancestors had already determined the best place to dig their system. The same occurred earlier: when canal systems that provide water to Phoenix were established, they followed the placement created by the sophisticated understandings of land and water use of the Hohokam.

Letitia Chambers is director of the Heard Museum.

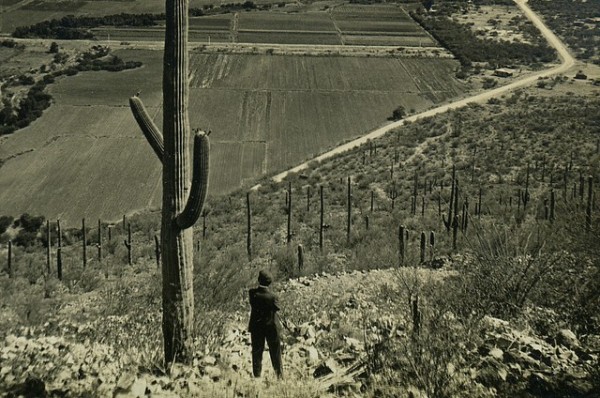

*Photo courtesy of waterarchives.