The Second Annual Zócalo Public Square Book Prize was made possible by the Southern California Gas Company with additional support from the Shepard Broad Foundation.

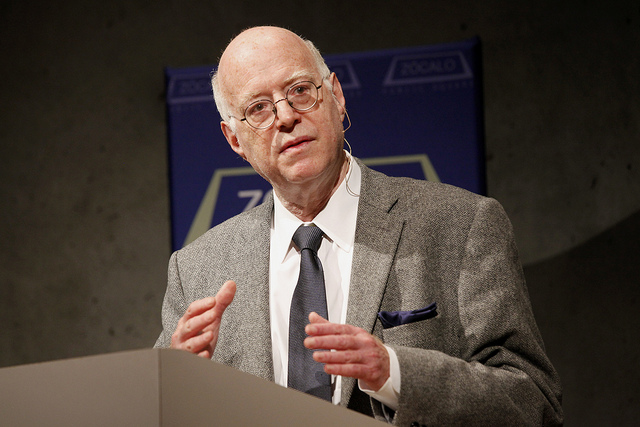

“Everybody in principle is for communal cooperation,” said sociologist Richard Sennett, winner of the 2012 Zócalo Book Prize for his book Together: The Rituals, Pleasures, and Politics of Cooperation. Yet cooperation in America today–in politics, in neighborhoods, in the workplace, and even in schools–is diminishing. Why is something we all agree on so difficult to accomplish? After accepting his award at MOCA Grand Avenue, Sennett, a professor at the London School of Economics, New York University, and the University of Cambridge, explored why people in our diverse society have so much difficulty working together–and how we might solve this pervasive problem.

Sennett has a long-standing interest in cooperation, which he defines as “working with other people to do what you can’t do for yourself.” As a young classical musician, he noted that one of the great traumas for “little hotshots” comes when they enter an orchestra or group setting for the first time. They think that if they can belt out their part individually, everything will be fine. “It brings them up short to have to play with other people and learn how to listen to them and cooperate,” he said. Almost all of us have the same experience in some walk of life, from team sports to the military, where “cooperation is a requisite for survival in the battlefield.” Cooperation is also a survival mechanism for infants, who begin to cooperate with their caretakers in the earliest moments of life.

In modern society, however, we don’t consider cooperation something needed; we look upon it as a “moral gift that we make to others”–and that’s where our problems begin.

A study by UNICEF of children in 22 developed countries found American students between the ages of 8 and 10 to be among the world’s least cooperative with their peers–and among the most consistent in practicing bullying behavior. “Our institutions early in life predispose people to withdraw from one another, to look at cooperation as a form of weakness, and to see aggression as a more durable way of relating to other kids,” said Sennett. Adults today are also less inclined to cooperate, thanks in part to modern technology. People have always tended to silo themselves, and e-mail has made it even easier not to share or communicate. Informal cooperation has diminished in the workplace as a result.

In our home life, Sennett has found that we trust our neighbors less than ever before. We don’t believe they would come to our assistance in the event of an emergency, and so we’re less likely to help them out in turn. This diminution of trust is toxic to cooperation. So how can we get people to trust–and cooperate with–not just their neighbors but also strangers, or even people they don’t like? In the past, when people lived in communities where everyone shared a background, they could draw on shared values, or the idea that “we’re all in this together.” But today, particularly in urban communities, people are mixed by race, class, ethnicity, and lifestyle. This diversity demands the most difficult form of cooperation, one that requires three skills: dialogical skill, the use of the subjunctive expression, and the practice of empathy.

Dialogical skill means good listening–trying to understand what someone is saying beneath their words. It’s different from dialectical expression, where people negotiate verbally–one person says “x,” the other person says “y,” and so on, until agreement is reached. And although dialogics doesn’t offer the same closure as dialectics, it is crucial to dealing with people who are different from us. Dialogical skill asks us to listen and try to understand where someone is coming from. “You can’t take things at face value, or else you won’t get very far in interaction,” said Sennett.

We also need to change the way we express ourselves if we want to cooperate better. We think of speaking in the declarative voice as a virtue: it’s how one makes a forceful argument with precision and clarity. But the subjunctive voice–which is more hesitant–opens up “a space of ambiguity” for conversation to continue. When I use the subjunctive, said Sennett, “I’m allowing room for us to interact.” Watching the news today, Sennett sees “not a conversation but a kind of opera in which one kind of person goes forward and does a solo, then the next one. There’s no exchange.” The subjunctive voice is also less aggressive and impassioned than the declarative, which means it can keep hostilities from flaring. As a labor arbitrator, Sennett found that when both sides were locked into clear positions, negotiations failed. But once the clarity on positions was muddied, a conversation could begin.

Our society places a premium on sympathy, said Sennett–whereby we feel someone else’s pain as our own and thus reach out to help. It’s a deep Judeo-Christian moral value as well–the notion that I’ve got to be able to feel what you’re feeling. Identification is at the root of sympathy. But “empathy is something a little cooler and a little tougher,” he said–and thus more useful in our society. It’s not about feeling someone else’s pain but being curious about what another person is going through–and then trying to figure out how best to help. “Empathy is a skill that we need when we’re dealing with people who we don’t understand, who are really different from ourselves,” he said.

Getting along today, and mobilizing a community, is no longer a question of solidarity but of cooperation. “We want to practice ways of cooperating across these barriers of difference rather than scrubbing them out in the name of solidarity,” said Sennett.

Early in the evening, Sennett noted that America “is a country whose political system has broken down by the inability of people to cooperate politically.” At the end of his talk, Sennett zeroed in on President Obama–whose strategies he called “an interesting case of one way not to practice cooperation.” In negotiations, Obama takes a dialectical rather than a dialogical approach. This restricts his ability to negotiate, as does his aloof personality. It’s not that Obama lacks conviction but that he is “too far removed from his enemies to find motives for diplomacy,” said Sennett. “Good negotiators don’t get themselves in the trap of thinking they can give and give until they reach agreement.”

Watch full video here.

See more photos here.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Amazon, Powell’s.

Read about what small-scale examples of human cooperation can teach us here.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors