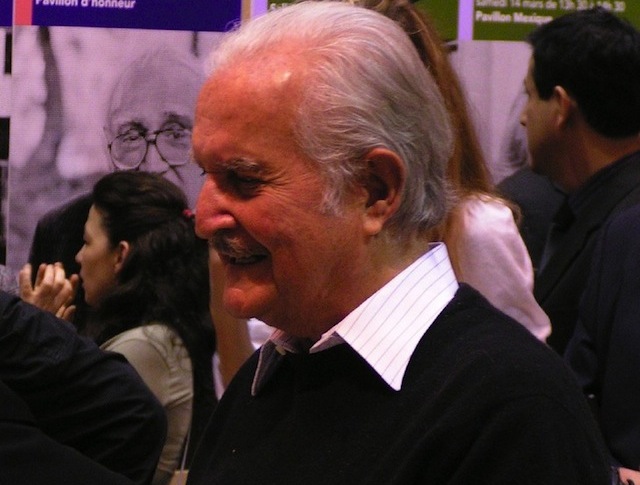

When the Mexican novelist and essayist Carlos Fuentes, who died May 15, visited Zócalo for an interview with Andrés Martinez in the fall of 2007, he talked about place, and places.

Los Angeles, he said, was a “confusing and beautiful” city that left him disoriented, puzzled, and still “very much at home.” He spoke of his life in London, and his appreciation both for its literary history (Dickens was his favorite) and for its “cold” and “miserable” present; the lack of warm people and good food made it an easy place to get writing done without distraction. And he discussed the difficult but improving relationship between Mexico and the U.S.–whose government had barred him from the country in the early 1960s because of his ideas.

“Now that’s over,” Fuentes said. “You’ve become civilized.”

Fuentes’ books–which included the novels The Death of Artemio Cruz, Terra Nostra, and The Old Gringo (the first book by a Mexican to become a U.S. bestseller)–were, at their best, an argument for a civilization that didn’t exclude anyone. Fuentes discussed his work, his life, and Latin America with Martinez in the Japanese Pavilion at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

AM: What kind of a relationship do you have with the city of Los Angeles? What does L.A. mean to you?

CF: It’s a beautiful and confusing–or confusing and beautiful–relationship, depending on the orders of the factors, because it’s a very difficult city to understand. It doesn’t let itself be grasped easily. It’s not easily understood. I’m disoriented a lot of the time, but in certain barrios I feel very much at home. I’m immensely interested in the people, in what’s going on in the shops, the restaurants, the movies–in everything that is going on in this beehive of a city.

AM: You spend about half your time in London. That’s an interesting choice for a Latin American novelist. Is this self-imposed exile?

CF: No, no it’s not exile at all, because I feel very comfortable in London. They leave me alone. I can write all day long. I don’t have to go out. The weather’s bad. The people are cold. The food is miserable. I read and write as much as I want to there, and in Mexico that’s impossible.

AM: Can you talk a little bit about the period of time during which you were actually barred from entering the United States?

CF: It was very curious. In 1962, I was invited by NBC to a discussion with [then-Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs] Richard Goodwin. When I asked for the visa I was barred, and I was then put in the “undesirable aliens” column from which not even God could escape. You’re in migratory hell, and you’re there forever. [But in 1967] I got an exemption from the Senate–from Senator J. William Fulbright. Now that’s over. You’ve become civilized.

AM: That partly reflects your speaking out a lot on political matters. I’d be curious as to whether, in addition to being a great novelist, you assumed the role of a social political commentator by choice? Or is this something that was forced upon you given your role as public intellectual?

CF: No, not forced upon at all. It’s by choice, and it comes from the fact that I grew up in a very politically active time, which was the New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt and the Mexican revolution of Lázaro Cárdenas. So I’ve had this political mind since then, and then there’s been a tradition in Latin America of speaking up for those who have no voice. That’s less and less true, because you have more and more people speaking today through agrarian co-ops, unions, the parliament, parties … When we had tremendous dictatorship in Latin America, the voice of the writer was much more important than it is now.

AM: So is the next generation of Mexican novelists going to be less political because they’re not forced into that space?

CF: Yes–they are less politically involved.

AM: Are there are books out there that you wish you had written?

CF: Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, William Saroyan’s The Human Comedy, and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment.

AM: If you had to pick one?

CF: I think with time the novelist I love the most is Charles Dickens. I would have loved to have written one of his books because it’s so much out of my possibility. I could have written a Dostoevsky novel, but not a Dickens novel, because there is this element of innocence in Dickens, an astonishment, which has left the modern world forever. And you have little Dora and David Copperfield. They’re a bit sentimental, but they’re so absolutely pure in their vision of the world that you wish you could recapture that. It’s like being in paradise for once.

AM: In the 1990s, we saw a lot of optimism about the transition in Latin America away from the age of military dictatorship to more democracy, and a sense that the capitalist model might actually render benefits for the majority of the population. Today, that seems to have stalled a bit. Do you feel optimistic about Latin America’s political future?

CF: As a whole I am optimistic. I think we’ve made gigantic strides in the democratic path. But people say, “Hooray for free elections, Congress, freedom of the press, freedom of opinion, everything you want! … And when do we eat?” The fact that social progress is not in the same rhythm as the political process makes many people impatient in Latin America. The democratic process has to move at a much brisker pace toward the fulfillment of people’s needs for work and health and education.

AM: When you travel through Latin America a lot of times you hear people complain that the U.S. does not pay sufficient attention to the region–

CF: –Thank God! It’s better that you not have too much attention. And that we diversify our relationships with Europe and with Asia. I think we should look more toward the Pacific, more toward Europe, and less toward the United States.

*Photo courtesy of ceronne.

Send A Letter To the Editors