In the late 1970s, Iranians emigrated by the hundreds of thousands, and a sizeable proportion of them found their way to Los Angeles. Today, Los Angeles County is home to over half a million Iranian Americans. They have changed their new home, and their new home has changed them. In advance of the Zócalo event “What Would a Persian Spring Mean For L.A.?” we asked several Iranian Americans to answer the following question: How have Iranian-Americans shaped Los Angeles, and how might they shape the future of Iran?”

Iranian Americans have shaped L.A. greatly–and now they’re also feeling accepted

The maitre d’ approached us with a broad mustachioed smile, cherry-red menus tucked under his arm. “Befarmah,” he said, a Persian phrase that, in this context, meant “welcome and please follow me.” We followed, past a chipped, gurgling fountain of blue tile, the walls lined with images of Persepolis–the once glorious seat of Persian power sacked by Alexander the Great–and spiraling turquoise spires of Isfahan.

The maitre d’ approached us with a broad mustachioed smile, cherry-red menus tucked under his arm. “Befarmah,” he said, a Persian phrase that, in this context, meant “welcome and please follow me.” We followed, past a chipped, gurgling fountain of blue tile, the walls lined with images of Persepolis–the once glorious seat of Persian power sacked by Alexander the Great–and spiraling turquoise spires of Isfahan.

The maitre d’ wore a crisply pressed though ill-fitting burgundy waistcoat, a clean white shirt, and black bowtie. He bowed ever so slightly, one hand on his chest in the Persian way, as we sat down. “Khosh Amadeed,” he said. Welcome. He glided away, pointing the finger at a busboy who dutifully poured us water and brought forth the requisite plate of feta cheese, radishes, mint, and parsley, accompanied by a bowl of cucumber yogurt and the flat bread known as sangak.

The maitre d’ continued his command of the restaurant in that manner–light and welcoming to guests, firm and brusque with staff (particularly with the mostly Mexican busboys). I detected an accent in his Persian, but I could not place it. The “khosh amadeed” gave him away. The “Kh” sound–imagine a snore, or someone faking a snore–was the bane of non-Persian native speakers. It came out as a “K” as in “Komeini,” or an “H” as in, well, “Homeini.”

Back then, I was a journalist with the journalist’s license (or presumption) to ask questions, so I discreetly asked our waiter–a native Persian speaker–about the maitre d’. The waiter laughed: “Yes, he is Mexican, but here in Tehrangeles, even the Mexicans speak Farsi.” The waiter called him over. The maitre d’ smiled, his mustache widening across his face, and came over. He likely knew what was coming: a table full of Iranians and Iranian-Americans–both bemused and beaming–as the Mexican performed his tricks of Persian.

He put on a good show, amusing the table with his earnest efforts to speak a language known in the Middle East for its poetic flourishes, expressing his love of Persian cuisine, and even remarking on the beauty of Iranian women, noting with a wink that he was single. (That last part brought some wide smiles from the ladies and some playful tsk, tsk “they are a handful” and “don’t be so hasty” jokes from the men.)

What he likely did not know was this: for many at the table, a collection of recently arrived immigrants, others who have lived in the U.S. for decades, and visitors from Iran, listening to a Mexican speak Persian and praise the refinement of Persian cuisine and the beauty of Iranian women meant something deep and profound: it meant, at least at this moment, in this restaurant in Westwood, Iran was not equated with terrorism or revolutions or Ayatollah Khomeini or hostage-taking. It was the Iran they knew, the one they loved, the one they brought with them to Los Angeles, one that has carried on in the imported nostalgia of young Iranian-Americans for a country they never knew, and in the older generation, simultaneously adapting to their new lives, but still living in their memory in an idealized past.

Yes, the statistics will show that Iranian-Americans have made a tremendous impact on Los Angeles and the wider the United States. They create jobs, they build companies, they heal the sick, they teach our young. They are among the most highly educated and affluent ethnic groups. They are accomplished doctors, engineers, bankers, real estate developers, professors. But as I reflect on Iranian-Americans in Los Angeles, I cannot help but think of the Mexican maitre d’, an enterprising fellow who rose through the ranks as dishwasher, bartender, and eventually head waiter, his well-thumbed Persian phrasebook in his waist coast pocket, who brought a sense of relief and hope to a table full of Iranian-Americans in a kabob house in Tehrangeles one autumn afternoon.

Afshin Molavi is a senior research fellow at the New America Foundation, a former Tehran-based journalist for The Washington Post, the author of The Soul of Iran, and an Iranian-American. He wishes he could spend more time in Tehrangeles.

————————————-

Iranians have bonded with their new home–while staying involved with their old one

The first large wave of Iranians to migrate to Los Angeles in the 1980s were pioneers in multiple respects. Not only did they work to establish new communities as immigrants; they also were among the first to harness the possibilities of ethnic media and satellite television to address co-ethnics on an international scale. Some broadcasters hoped for political change back home, while others saw entrepreneurial opportunities in reaching Iranians far and wide. What they had in common, of course, was the use of satellite media as a method for maintaining connections to home and their fellow Iranians, many of whom were now living transnational lives. These connections were important for the sharing of both news and cultural forms that contributed to a continued sense of shared identity in the face of assimilation pressures, ongoing political hostilities, and at times an unwelcoming host society.

The first large wave of Iranians to migrate to Los Angeles in the 1980s were pioneers in multiple respects. Not only did they work to establish new communities as immigrants; they also were among the first to harness the possibilities of ethnic media and satellite television to address co-ethnics on an international scale. Some broadcasters hoped for political change back home, while others saw entrepreneurial opportunities in reaching Iranians far and wide. What they had in common, of course, was the use of satellite media as a method for maintaining connections to home and their fellow Iranians, many of whom were now living transnational lives. These connections were important for the sharing of both news and cultural forms that contributed to a continued sense of shared identity in the face of assimilation pressures, ongoing political hostilities, and at times an unwelcoming host society.

As Iranians gradually recognized their move to Los Angeles was a permanent one, they also recognized the need to invest culturally, politically, and economically in their new home. After establishing an ethnic enclave in Westwood (a.k.a. Tehrangeles), over the last 15 years Iranian American individuals and organizations have become more active in promoting Iranian culture and civic participation in greater Los Angeles.

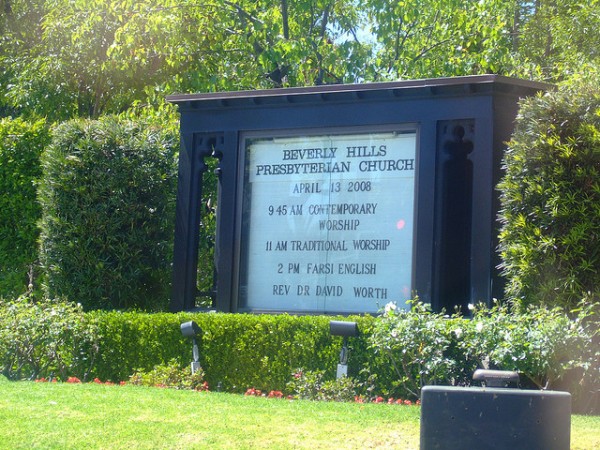

Today, among L.A.’s more prominent citizens are Iranian-American real estate moguls, fashion designers, and plastic surgeons who have changed the literal and figurative face of Los Angeles. Iranians now celebrate Norooz (the New Year) in several of the city’s most important institutions and public spaces, including City Hall and LACMA, and trumpet the coming of spring on billboards and banners along the busiest streets of the city. Iranian Americans increasingly run for public office and serve as officers in the LAPD, as judges in L.A.’s immigration courts, and as educators in LAUSD schools. In doing so, they bring cultural diversity to public service while increasing public support for and awareness of Iranian communities.

At the same time, it would be a mistake to assume that, by virtue of their more focused engagement in American life, Iranian Angelenos are therefore disengaged from Iran and Iranians abroad. On the contrary, many L.A. Iranians continue to live transnational lives and to use various forms of media to create and maintain social, cultural, and political connections to Iran. The continuing influence of L.A.-based Iranian media producers suggests just one of many possible roles that Iranian Americans in Los Angeles can play in the future of Iran.

Amy Malek is a PhD Candidate in Anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles and serves on the board of Iranian Alliances Across Borders (IAAB), a non-profit organization seeking to strengthen the Iranian diaspora community through leadership and educational programming.

————————————-

Iranians have brought scholarship and know-how to Los Angeles–and they seek to bring the same to Iran

Iran is an old nation that has existed for thousands of years. Iranians have made a countless number of great contributions to humanity and civilization. The Iranian culture is deep and rich. Therefore, anytime the people of such a nation emigrate to another land, they take with them a piece of their history, traditions, culture, and other virtues and achievements. At the same time, Iran is far from the United States and Los Angeles. It is not easy for an Iranian to move here. The vast majority of the Iranians that have moved to the United States, and in particular, to southern California, belong to one or both of two groups: the highly educated or the highly business-savvy (or both).

Iran is an old nation that has existed for thousands of years. Iranians have made a countless number of great contributions to humanity and civilization. The Iranian culture is deep and rich. Therefore, anytime the people of such a nation emigrate to another land, they take with them a piece of their history, traditions, culture, and other virtues and achievements. At the same time, Iran is far from the United States and Los Angeles. It is not easy for an Iranian to move here. The vast majority of the Iranians that have moved to the United States, and in particular, to southern California, belong to one or both of two groups: the highly educated or the highly business-savvy (or both).

From the streets of Beverly Hills, Blair, and Santa Monica, to Westwood, Los Angeles, the Valley area, and Pasadena, one can easily see the imprints that the Iranians have left. We see Iranians deeply involved in some of the most sophisticated and future-looking scientific and technological projects–a trip by astronauts to the planet Mars, carrying out cutting-edge research at USC, UCLA, and Caltech. We see them running some of the most essential services of the city as engineers in such organizations as the Department of Water and Power. We see Iranians involved in charity. We even see them getting into Hollywood in ever-increasing numbers.

But that is not all. We also see the contributions of Iranians to passionate political debates about what is going on in Los Angeles, California, and the nation as a whole, as well as what is going on around the world. And it is here that the Iranians living in this area may contribute to a better future Iran with a more representative government. Iranians and Iranian-Americans deeply care about their native land. They are proud of their heritage, and they wish to help preserve the old land and its glories for future generations of Iranians. They would love to contribute to the development of Iran and build a bridge of friendship between their native land and their adopted country, the United States. But, for that to happen, a democratic political system must first emerge in Iran that is based on the rule of law, respect for the fundamental rights of all the citizens, regardless of their gender, religion, and ethnic background, and free and fair elections that allow the citizens to elect their leaders.

That is why Iranian Americans have over a dozen satellite television stations broadcasting into Iran. Iranians publish newspapers, magazines, and books, and prepare and publicize reports about what is happening within Iran, acting as the voice of those Iranians who cannot be heard. They are involved with advocacy groups at the national level, trying to influence the policy of the United States toward Iran in one way or another.

The views espoused by the activists differ widely, but most of them have one goal in mind: to contribute to a better Iran of the future, which in turn will help re-establish friendly relations between two of the greatest nations on earth, the United States of America and Iran.

Muhammad Sahimi is professor of Chemical Engineering & Materials Science and the NIOC Chair in Petroleum Engineering at the University of Southern California.

*Photo courtesy of HeyRocker.