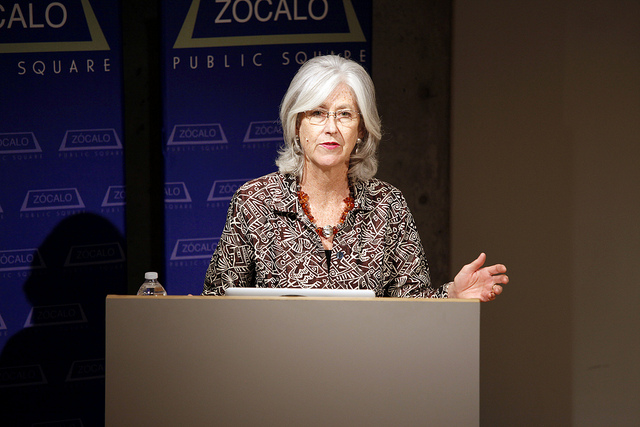

Shannon Brownlee, acting director of the New America Foundation Health Policy Program, began an event sponsored by the California HealthCare Foundation by taking a survey of the crowd at MOCA Grand Avenue. She asked audience members to raise their hands in order to let her know how they wanted to die. The crowd was nearly motionless as she went through her list: heart attack, stroke, cancer, Alzheimer’s, frailty. But when she asked who wanted to die in bed at age 90, after playing tennis, eating dinner, and making love, almost all hands shot up.

But the reality is that most of us are going to die after spending the last three to 10 years of our lives suffering from increasing frailty and dementia—and America is totally unprepared for the number of people who will go through this in the next few decades as the baby boomers age.

“We haven’t thought about the medical care we need, or the medical care that we prefer—which isn’t often the kind of care we receive,” said Brownlee. This is true for the nation broadly and also for individuals and families.

Take a patient Brownlee called “Helen T.” Helen was admitted to Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital emergency room with a broken hip; she was suffering from advanced Alzheimer’s and had an advance directive indicating that she didn’t want intubation or CPR. But her daughters were told by a surgeon that unless their mother was operated on, she would be in a lot of pain—and although the operation required intubation, the surgeon said that the advance directive could be reversed temporarily. Her daughters agreed to the surgery, beginning a two-month-long odyssey in which Helen was shuttled back and forth from her nursing home to the ICU to receive many different treatments beyond simply repairing her hip, including a catheterization, a cardiac stent, multiple intubations, treatment for pneumonia and a urinary tract infection, and a tracheostomy to insert breathing and feeding tubes.

Ultimately, a palliative care team was brought in, and Helen’s daughters agreed that her mother wouldn’t want any of this treatment; she died peacefully in hospice surrounded by her children and grandchildren.

“Every person involved in Helen’s care wanted what was best for her” and were aware of her advance directives, said Brownlee. But there were many points along the way where different decisions could have been made. Cases like these, she said, are about communication and denial.

Doctors present families and patients with choices that seem stark: death or treatment. But they aren’t upfront in letting people know when treatment won’t improve a patient’s quality of life. Nor do they normally present another option: to make the patient as comfortable as possible as he or she dies. The problem is compounded by various specialists who don’t see the patient as a whole person but instead see individual issues that can be resolved.

Nobody, said Brownlee, told Helen’s daughters, “‘We can make her comfortable without surgery’—nobody said that.”

“Why do people find themselves on this train that leads toward more and more and more [care], even if they sign an advance directive?” she said.

People think more is better when it comes to medicine—more drugs, more time in the hospital, more treatments. So part of it is patient preference. But a great deal depends on where you live, and what hospital you’re admitted to. Within California, there are huge differences between how patients are cared for at the end of their lives in the northern and southern parts of the state, Brownlee said.

According to Brownlee, in 2007 chronically ill patients at UCLA Medical Center spent an average of 14 days in the ICU in the last six months of their lives—more than three times longer than patients at UCSF Medical Center, and longer, too, than patients at Cedars-Sinai, who spend an average of 9.6 days in the ICU.

The use of palliative and hospice care has risen over the past decade, and fewer people are dying in hospitals, said Brownlee, but there remains a tremendous gap between the care patients want and the care they receive.

In 2003, 33.8 percent of patients in California died in the hospital. In 2007, that number dropped to 31 percent. But the average in the rest of the country is 28 percent. And in the Los Angeles area you are significantly more likely to die in the hospital or after spending time in the ICU than you are in other areas of the state.

It’s counterintuitive, but this regional variation is a result of greater availability of ICU beds and hospital beds. In areas where there are more beds per capita, more people are admitted to the hospital, and are thus more likely to die in the hospital. As a result of a post-World War II building boom, California (and Southern California in particular) has many small hospitals. Los Angeles has more doctors per capita than any other place in the country, said Brownlee.

And because of the economics of our healthcare system, hospitals, much like hotels, don’t make money with empty beds.

So how can we move toward a system that gives people the care they want, rather than the care determined by the region where they live or the number of beds in the nearest hospital?

“In my ideal world I imagine a health system in which patients no longer feel like widgets, and doctors no longer feel like factory workers,” said Brownlee. She wants to see “a world where doctors really talk to their patients,” where care shifts away from hospitals and into the home, and where primary care doctors have more time to treat their patients.

She also thinks we need more trust between doctors and patients. Doctors, she said, “see you as a walking lawsuit waiting to happen”—and you can’t trust someone you think wants to sue you.

Every time you go to the hospital or a doctor’s office, she advised the audience, you should think, “No decision about me without me.”

She also said that a fundamental shift is needed in how patients evaluate the care they receive; we tend to think that the doctor who gives the most tests and uses the most technology cares the most.

At stake isn’t just our health and comfort but also the economic future of the nation, said Brownlee—which is why we all need to start talking and thinking about death now, before it’s too late.

In the question-and-answer session, audience members shared their experiences with terminally ill and elderly family members and asked Brownlee where to go for more information on regional variations in end-of-life care.

Brownlee said that she is preparing reports for the California HealthCare Foundation on end-of-life care, cancer care, and variation rates of certain types of procedures all over the state; these will be available on the foundation’s website early next year.

Is there any financial incentive for hospitals not to offer palliative care? “Hospitals are paid for offering more care, not better care,” said Brownlee, adding that the Affordable Care Act will change that to some degree—but that patient demand is what will ultimately force hospitals to offer more palliative care.

Brownlee believes that change can come to America’s end-of-life healthcare. “It’s going to take a lot of patient voices, and a lot of leader physician voices,” she said.

Send A Letter To the Editors