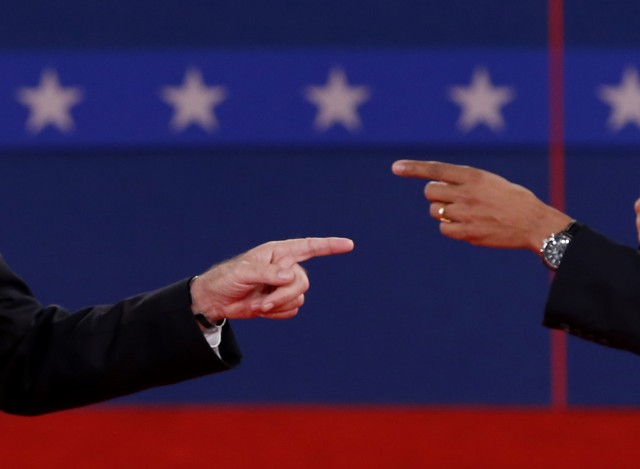

While Republicans and Democrats engage in their scorched-earth, zero-sum version of political warfare, a majority of Americans with moderate views and a desire to see their representatives come together to solve problems look on in disgust. In advance of a Zócalo event in Scottsdale “Are Political Parties Hurting our Democracy?” featuring former Republican congressman Mickey Edwards, we ask a number of experts whether a third party could be part of the solution.

A third or multiple parties would likely have a number of benefits, raising additional issues at the national level and providing voters with added channels of political awareness and influence, but adding more parties wouldn’t directly alter the partisanship and dysfunction of contemporary politics. For that, reform would have to focus on the root causes of that dysfunction, rather than simply the number of participating players. The challenge of today’s party system, and efforts at a multiparty system, is to balance the representation of the interests of like-minded partisans with the need to cooperate and compromise with those not in one’s party. The polarization—the dysfunction—we see today in part is related to the desire of these like-minded partisans to see their way as the only way to move forward, without ever desiring to reach out to the other side. Though Republicans have been masterful at this over the last four years, Democrats have also shown little inclination to compromise. And so the public good gets lost in the ideological absolutism of the two sides. In the 1960s and 1970s, the liberal Republican and conservative Democrat played the role of go-between for the two parties and pulled partisans from their side and ideologues from the other side together to overcome political gridlock. Today, those go-betweens have been vilified by members of their parties and are disappearing from the political stage. While a multiparty system provides a greater opportunity for bringing more voices to the table, it does not necessarily mean that the dysfunction or partisanship will erode. Democrats and Republicans are not simply going to agree more with one another or the third or fourth party.

DeWayne Lucas is professor of political science at Hobart and William Smith Colleges and chair of the American Studies Program. His research and teaching interests include political parties and legislative behavior.

We need a systematic, fundamental change to our political system. Many of the challenges we face—legislative gridlock and partisanship amongst others—would be significantly reduced by the introduction of third parties and independent candidates. Americans are entitled to a government and political system that works, one driven by shared purpose and common sense. This cannot be achieved with only two parties dominating the political landscape. We need to open up the process. For years I have been a strong advocate of movements that develop political alternatives to the two major parties. Open primaries would go a long way to break down the hold of partisanship on the democratic process. We should more broadly open up ballot access for state, local, and national office as part of the overall political reform process. We are currently investing independent expenditures for Angus King, independent candidate for a Senate seat in Maine and the former governor, through Americans Elect, an organization set up to recruit independents to run for President this year. Though it did not succeed in finding a candidate for president, it has now turned its focus to electing independents at the state and local level. I hope that there will be a broad movement in 2016 to encourage independent candidates to enter the fray. We need new ideas and new approaches to jumpstart a sclerotic political process. Infusing the system with fresh thinking on this issue is our strongest weapon against partisanship and political dysfunction. We need more voices in the system, not less. We need reconciliation, bi-partisanship and cooperation. We have no hope of achieving solutions to our trenchant fiscal, economic, social, and international problems without a fundamental change to how politics is done in the U.S. Third party alternatives and independent candidates offer the best hope of creating viable and long lasting solutions to these crises. And while there’s no panacea in opening up the system, one thing is for sure: if we don’t encourage more voices and more people to come into the political process, we all lose.

Douglas E. Schoen is a Democratic pollster, strategist and consultant. He has worked on numerous campaigns, including those of Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, Michael Bloomberg, Evan Bayh, Tony Blair, and Ed Koch. His most recent book is American Casino: The Rigged Game That’s Killing Democracy.

At the elite level, more parties would be a welcome development. Politicians would be much more likely to reach across the aisle—or aisles. When no single party commands a majority, representatives must compromise across party lines to pass legislation. Broader coalitions—and more potential coalitions—allow a greater number of issues to reach the bargaining table. Partisan bickering or stonewalling become more costly. And, traditional left-right issues are transformed to be more nuanced and less partisan. One potential downside: it’s harder to hold parties accountable when they work together. When a coalition’s policies fail, who should the public vote out of office? Of course, for voters, more parties mean more choice, and thus closer personal connections to parties’ platforms and their candidates. What’s more, an individual’s vote may make more of a difference when there are multiple parties competing to win elections. Yet, partisanship may take a new shape. Instead of choosing one’s lesser of two evils, voters may identify with parties that squarely represent their interests on a number of issues. One potential downside: choosing among multiple parties requires greater information and political sophistication, creating a wider gap between those who are politically educated and those who are not. Of course, none of this will occur without a change in our electoral system. Single member plurality districts (i.e. “winner take all” or “first past the post” systems) are known for having enduring two parties. A switch to proportional representation—as in most of continental Europe or Latin America—could encourage greater voter participation and elite cooperation. Short of that—especially with a president rather than a prime minister—we should expect the Democrats and Republicans to remain our only two choices for a long time.

Georgia Kernell is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and a Faculty Fellow at the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University.