In Squaring Off, Zócalo invites authors into the public square to answer five questions about the essence of their books. For this round, we pose questions to Robert W. Bennett, a constitutional law professor at Northwestern University and author of Taming the Electoral College.

Bennett has written extensively on perilous aspects of the Electoral College, a system created by the Founding Fathers over 200 years ago. America’s presidential election process is one of the most complicated in the world, and it can create odd situations where the winner of the presidency doesn’t have a majority of the popular vote, electors change their minds about whom to vote for, and candidates devote campaigns to a handful of swing states.

-

The framers of the Constitution created the Electoral College to serve as a buffer between the people and the presidency during a very different time in America. Do you think it’s an antiquated system that needs to be thrown out, or should certain aspects remain?

If it could be done smoothly I would readily substitute a nationwide popular vote for the Electoral College, but doing it smoothly would not be easy. One reason is that the right to vote varies from state to state. Perhaps most important are differences in things like photo ID laws, early voting, and voting day registration. As a result there would be no integrated nationwide vote. That isn’t to say there are no problems with the Electoral College as is—chief among them the possibility that an election result might be turned around by “faithless electors” who do not vote for the candidate(s) of the parties that nominated them as electors. -

Speaking of these “faithless electors,” they could become an issue in this election, as poll watchers and political pundits say a tie—Romney and Obama each getting 269 electors—is a possibility. How common is it for an elector not to vote for the candidate he or she has pledged to vote for, and do any states have laws against it?

The number of faithless electoral votes over the years depends in part on what counts as “faithlessness,” like refusing to vote for someone who has died. But clear-cut cases in presidential elections do occur. There was a “faithless” abstention in 2000 and a faithless vote for John Edwards for president in 2004. But faithless votes have never changed a presidential outcome, and for that reason many remain unconcerned about the possibility. Still, more than half the states do have laws that forbid or discourage the practice, but they do so in various ways. Some extract pledges of faithfulness; some say voting faithlessly constitutes resignation from the office of elector; some forbid faithlessness outright but without mention of penalty. In part because of the variation, the Uniform Laws Commission has formulated a Uniform Faithful Presidential Electors Act (an effort I am involved in) and will be pushing for state-by-state adoption after the upcoming election. -

The most popular argument against the Electoral College is that it can allow someone to become president despite failing to win the popular vote, which has happened four times: 1824, 1876, 1888, and 2000. Should that be tolerated?

With an election this close, it is entirely possible that there will be a winner of the electoral vote who “loses” the popular vote count across the nation. The quotation marks around “loses” are important, however, because the rules of the game—well known to both major candidates—are that the electoral vote winner wins. Had the popular vote been what matters, the campaigns would have been waged differently, spending lots of time, for instance, in California. So we don’t really know who might have won the popular vote under different rules in the years you mention. Still, there is no doubt that the rules contemplate the possibility of our electing a president who might not be able to carry a majority of ballots cast nationwide. As with the apportionment of the United States Senate, this is a reminder that we are designed to be a union of states, not individuals. -

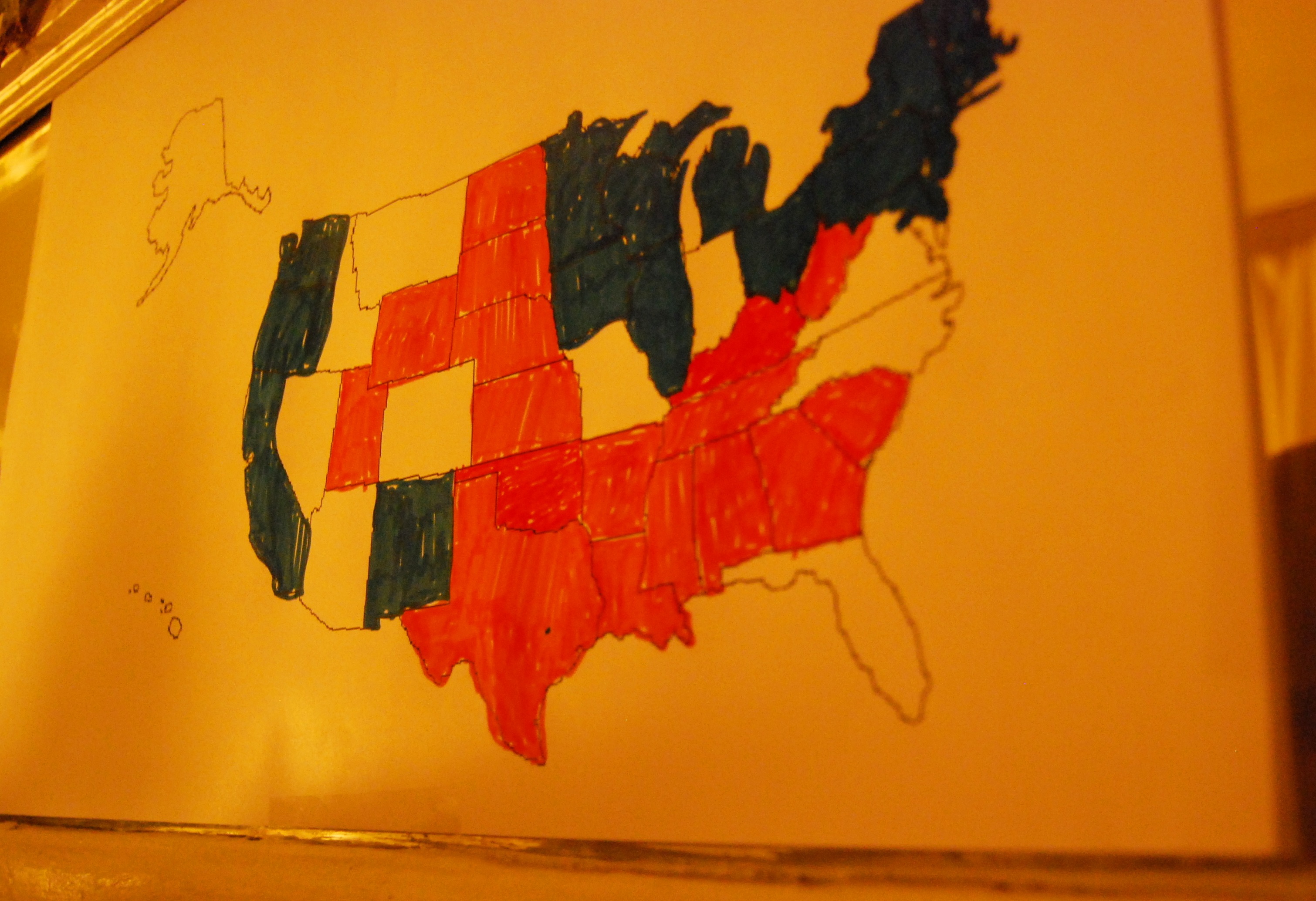

As a result, the electoral college creates an environment where candidates spend an exorbitant amount of time and money in swing states like Ohio and Florida but pay little attention to most of the country. Is it fair for an election to come down to a handful of states?

That is the worst consequence of the Electoral College mechanism. But, to be fair, a nationwide popular vote would also cause candidates to concentrate on some voters to the neglect of others. Candidates would go where they could “harvest” votes most efficiently, likely the most populous states. -

Past attempts at changing the Electoral College have inevitably failed. How likely is it, really, that changes—either by constitutional amendment or state-by-state laws—will be realized in the near future?

The optimal scenario conducive to moving to a nationwide popular vote would likely be an Electoral College victory for Obama combined with Romney capturing a clear majority of the nationwide popular vote. That would mean that each party had been “burned” by the present system within four elections. Short of that, I hope we’ll see widespread adoption of the proposed Uniform Faithful Presidential Electors Act. That effort, too, would be advanced by a close electoral college count in the coming election and either some actual faithlessness or evidence of efforts to court it.