They may be the most easily recognizable four notes of music ever composed, but the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony confounds orchestras and conductors with its very notation: a rest that Boston Globe music critic Matthew Guerrieri, author of The First Four Notes: Beethoven’s Fifth and the Human Imagination, called “a little slice of nothing.”

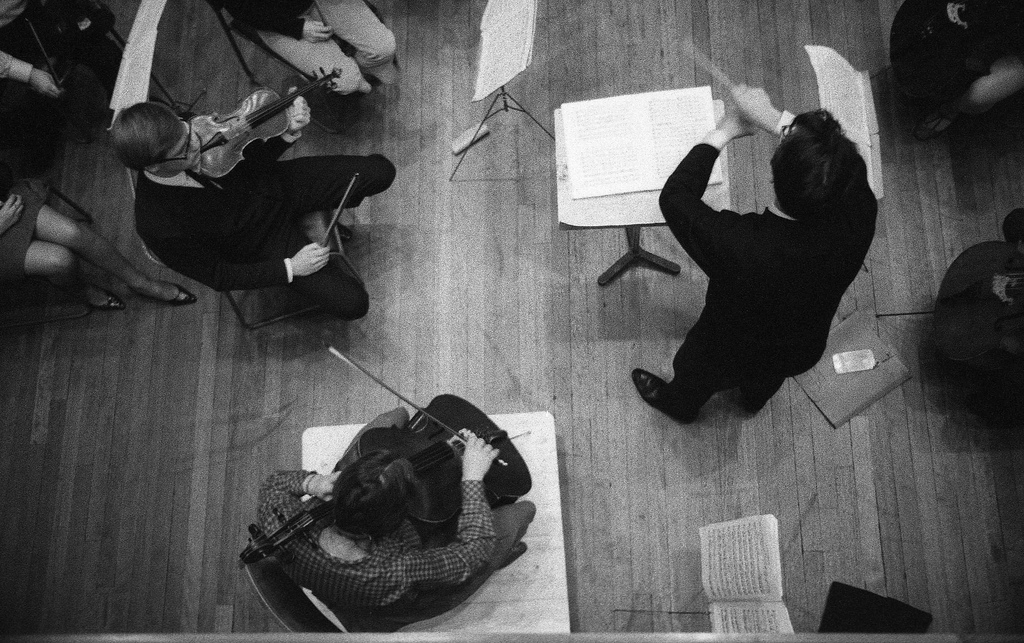

Zócalo editor T.A. Frank opened his conversation with Guerrieri by asking the crowd at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, at an event co-presented by the Arizona State University Center for Science and the Imagination, to guess the correct time signature of the piece. About half of the audience correctly identified it as 2/4. When Frank prodded Guerrieri to conduct the audience in singing those infamous first four notes in unison, again just about half of the group was successful.

Guerrieri explained that the easiest thing for a conductor to do in order to ensure a harmonious opening is to give the orchestra a beat before the rest. But that has other hazards: “It’s the sort of thing that other conductors will regard you as less of a conductor for doing,” he said “It’s become this odd sort of contest to see who can do the most grand gesture.”

So what, besides their familiarity and difficulty, makes these notes so special—what makes them genius?

Guerrieri explained that when Beethoven wrote the piece, there was a tradition of symphonies beginning with “slow, grand statements.” Beethoven, instead, starts the Fifth with a fast tempo, only to pull the rug out from underneath listeners’ feet by stopping immediately—then stopping and starting and stopping again before the piece starts up in earnest. It was shocking in Beethoven’s day, said Guerrieri, for its abruptness, for being “nakedly aggressive,” and for being “such a direct piece of music.”

But beyond shock value, asked Frank, what is it that makes Beethoven a genius?

Guerrieri said that it’s a combination of traits, the first being the almost athletic genius of playing the piano: “It’s muscles, it’s using your body, and it’s making your body do something on command,” he said. But it’s also about a “daisy chain of connections,” from physical talent with the instrument to translating that talent onto a page of written instructions to mastering that talent and taking it somewhere new. On top of all this, Beethoven had these skills at a young age, which set him apart from his contemporaries.

But he also had another form of brilliance: “the genius of making a career out of it.” Beethoven, said Guerrieri, “very consciously manipulated and leveraged his fame, which at the time was an unusual thing.” We take it for granted because we live in a celebrity-driven culture, but in Beethoven’s day, lasting celebrity—particularly for a composer—was something new.

Beethoven, like a lot of geniuses, was something of an outsider, said Frank—it’s a thread that seems to run through the stories of brilliant people.

Guerrieri said that this idea—of an artist or genius being apart from everyone else—is a Romantic one that in fact started with Beethoven. The German Romantics adopted him as their example of a genius with more privileged access to the sublime and to ideas beyond conventional human understanding. The Romantics were also the first to consider madness to be a symptom of genius—and you can see this start with Beethoven, who was so legendarily irascible and antisocial.

Beethoven was also celebrated because he was deaf—and thus perceived as being shut off from the world so he could receive divine inspiration without interference. This idea was reinforced when, in the 1860s, his body was transferred to a new tomb, and his skull was discovered to be unusually thick—which, wrote Richard Wagner, also helped him get inspiration from above without the rest of the world interrupting.

Today, said Frank, the study of creativity and genius is an interdisciplinary field, with neuroscientists and social scientists and music teachers offering studies and instructions on unleashing the genius within all of us. Yet we haven’t produced a Beethoven recently. What, he asked, is wrong with us?

Guerrieri said he didn’t know if the cultural world will ever produce a figure like Beethoven again. His incredible fame came in part because of the small circle he inhabited—he could “encompass the entire scope of the area in which he could become famous.” Today, there are so many more niches and styles and genres that the same level of cultural saturation is impossible. “There probably are geniuses of Beethoven’s level out there,” he said. “But they will not become the sort of overpowering, universal figure that Beethoven did.” It’s not losing something, he added—it’s our cultural life getting richer.

Frank quoted a 1970s Paul Masson advertisement proclaiming that the amount of time it took Beethoven to compose the Fifth Symphony—four years—is proof that “some things can’t be rushed: good music and good wine.” Is being slow or labored part of genius?

It can be, said Guerrieri, and it certainly was for Beethoven. But that plodding pace is about the homework and discipline that genius requires. If you look at geniuses, they put in the work, he said—they’re honing their craft all the time, whether they’re James Joyce or Beethoven or George Gershwin. The one great example of Beethoven’s genius, said Guerrieri, is that there’s no shortcuts to it.

In the question-and-answer session, an audience member asked how Beethoven would feel about tonight’s discussion: What would he think about being labeled a genius—and did he consider himself to be one?

“My guess is he would’ve scolded you for calling him a genius, but he would have agreed with you,” said Guerrieri. In a conversation late in life, Beethoven’s nephew told him he was famous for being deaf—and Beethoven “smacked him down a little.” Beethoven felt that he was a genius, but he also felt he worked hard for it. And he didn’t want to become a novelty act—the deaf composer. “I think,” Guerrieri concluded, “he knew how good he was.”

Send A Letter To the Editors