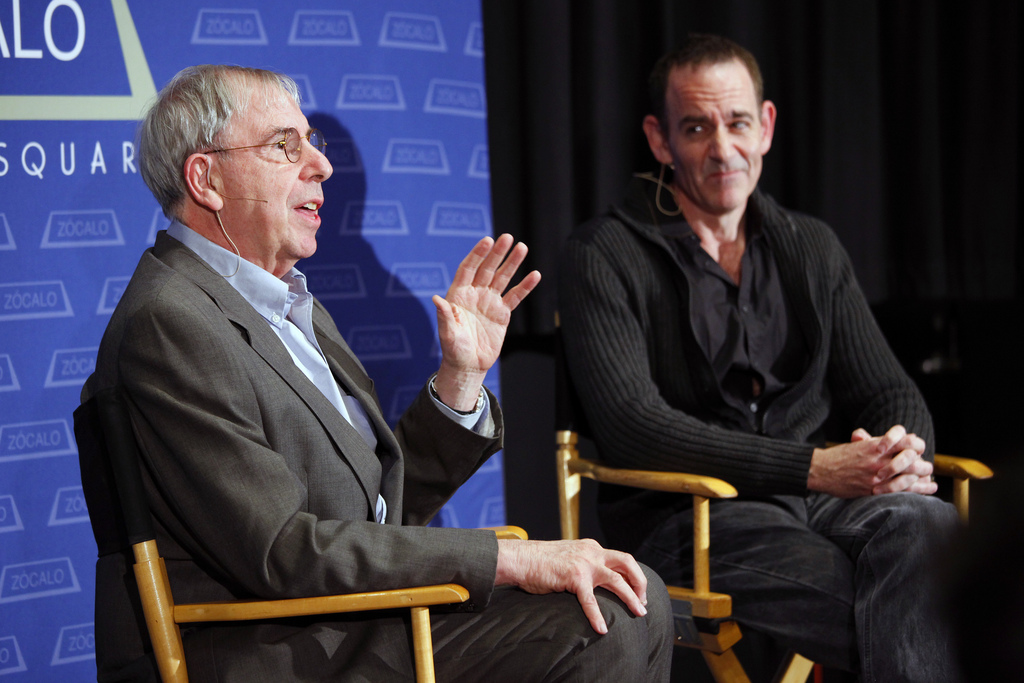

Even a century after Richard Nixon’s birth, his life and political career are still almost always considered in light of his demons and dark side. But former New Yorker editor Jeffrey Frank, author of Ike and Dick: Portrait of a Strange Political Marriage, chose to dissect Nixon in an entirely different context—that of his relationship to his boss and eventual in-law, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, for whom Nixon was a two-term vice president.

“It’s amazing how mean” Eisenhower was to Nixon, former Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum director Tim Naftali, the evening’s moderator, told the crowd at the Goethe-Institut Los Angeles.

“I don’t think Eisenhower was aware of it,” said Frank. The general-turned-president tended to see all of his colleagues as staff. And, although Eisenhower wasn’t a kind boss, he “was almost oblivious in some ways of his effect on people.”

The moment that set the tenor for their relationship came in the fall of 1952, during Eisenhower’s first campaign for president. Eisenhower knew very little about the man sharing his ticket; Nixon essentially had been selected by Eisenhower’s advisers. But after Nixon was accused of being funded by a secret group of millionaires, Eisenhower wanted him off the ticket. Nixon’s famous “Checkers speech,” a reference to a dog he received as a gift, saved his candidacy.

“From that moment on, in some ways things were never the same,” said Frank. Every year, Nixon remembered March 23 as the anniversary of the Checkers speech that had resurrected him. But the fund crisis and speech also ensured that Nixon could never let his guard down when it came to Eisenhower.

How, Naftali asked Frank, did the Republican party of Nixon and Eisenhower differ from the party today?

In the 1950s, said Frank, the Republican party was still the civil rights party, and the party of Lincoln. Until 1960, even Martin Luther King Jr. was a Nixon supporter.

Some historians believe that we can see hints of the darker side of Richard Nixon—the side we’re familiar with thanks to the Nixon White House tapes—in the 1950s. But others think that this side emerged because of later traumas. Which camp, Naftali asked Frank, are you in?

Frank said that he thinks there was a change in Nixon, and that “it probably dates from the very beginning of his relationship with Eisenhower.” From the moment he got on the vice presidential ticket, and even after the 1956 election, Nixon was under constant strain and pressure. He never knew that his job was secure. Back then, vice presidents weren’t considered the automatic heirs to the presidency, so Nixon still needed Eisenhower’s support during their second term in office together.

Naftali said that he’s noticed a contradiction between the private Nixon—the one we hear on the tapes—and the public Nixon. In Nixon’s State of the Union address, for example, he declares pride in the Environmental Protection Act. But on the tapes, over and over again, he identifies environmentalism with liberalism and calls this legislation a mistake. Was he at war with himself as early as the 1950s?

Frank said that he’d been similarly fascinated by the thread of Nixon and civil rights. Nixon was in touch with Martin Luther King Jr. regularly after meeting him in Africa in 1957. And Nixon expressed empathy and support for Fred Morrow, the only black man in the Eisenhower White House. But some of the things Nixon said in the later White House tapes were deeply racist. What to make of it? “Presidents vent,” said Frank. “The job is horrible.” A lot of presidents didn’t sound so great privately—Harry Truman used slurs to refer to blacks and Jews—but it’s what they do that counts, he said.

Could Nixon have avoided his self-destruction had he been elected in 1960? What, asked Naftali, would have happened?

“Would we have had Vietnam?” asked Frank. We wouldn’t have had a Kennedy assassination, he said. And had Nixon become president even earlier—if, say, Eisenhower hadn’t recovered from 1957 stroke—he would have been a younger, less traumatized president.

Instead, John F. Kennedy’s assassination became what Frank called “the worst thing that happened to Richard Nixon.” By 1963, the Nixons had moved to New York City, and the former vice president, who had just lost a race for governor of California, seemed to be on his way to elder statesman status. His family was happy in New York, and his Wall Street law firm job was a good one.

“It sounds like a Frank Capra movie!” said Naftali.

But a week after Kennedy was shot, Nixon was in meetings with the GOP about running in 1964.

What effect, asked Naftali, did the post-assassination 1960s—the counterculture, the Vietnam War, and the anti-war demonstrations—have on Nixon?

From the moment he was inaugurated, he felt under siege, said Frank; neither Nixon nor his family had had much contact with the counterculture, and suddenly people were throwing smoke bombs and tomatoes. On top of this came the leaking of the Pentagon Papers, which Nixon felt threatened by. All this “hit him like a stun gun,” said Frank.

Nixon had always had very few friends, but once he became president he was friendless and lonely. Together the enormous power of the office and his own enormous insecurity became “a really deadly combination,” Frank said. That’s what brought Nixon down, he added.

“He was always evolving,” Frank concluded. “Not always in a good way, but he was always evolving.”

Send A Letter To the Editors