Brooklyn earns a special place in the Jackie Robinson story. The borough’s robust mix of striving immigrants and progressive politics made for congenial fans when Jackie Robinson brought down the color bar in baseball (although, to be fair, within a few weeks Robinson was earning plaudits and admiration in the rest of the country too—even Philadelphia, where the racial harangues at the time were especially poisonous).

But UCLA deserves a chapter, too.

Jackie Robinson was born in the segregated South but was just a few months old in 1920 when his family arrived in Southern California. Pasadena, where the Robinsons settled, wasn’t Palmetto, Georgia, but there was still plenty of unofficially enshrined segregation (an unwritten law at local movie theaters put black families in the balcony and whites on the main floor). But Jackie Robinson wouldn’t be commanded to move to the back of the bus until serving as an officer in the U.S. Army at Fort Hood, Texas, in 1944. The same U.S. Army that so valiantly vaulted oceans to fight for freedom was segregated.

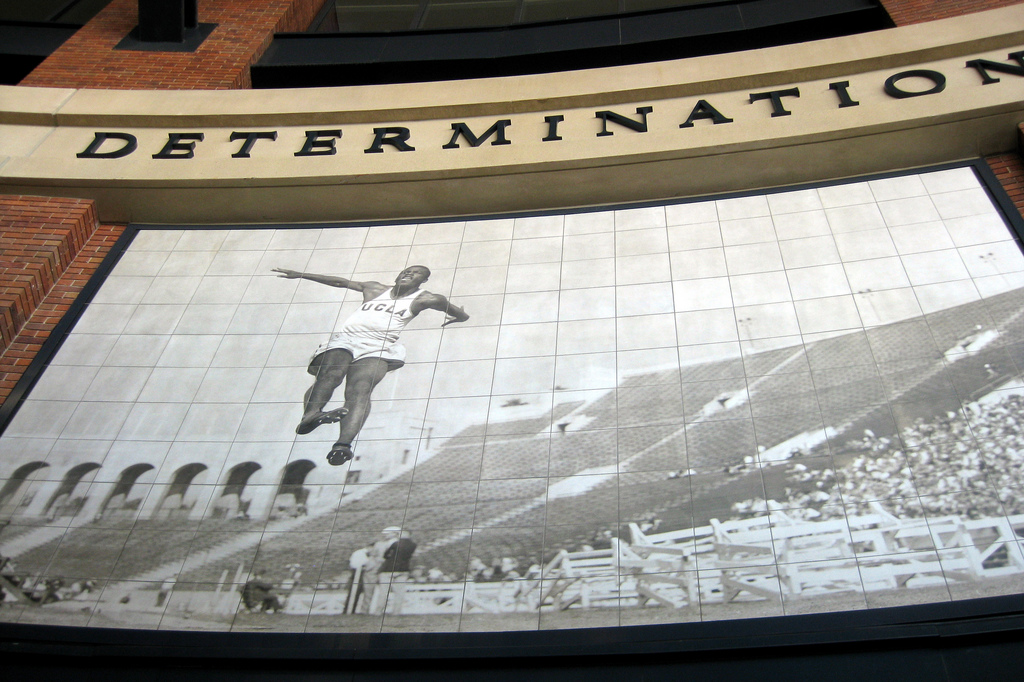

Jack Roosevelt Robinson was, by all accounts, the best all-around athlete at Pasadena’s John Muir High School. He played shortstop and catcher on the baseball team, quarterbacked the football team, played guard on the basketball team, and won both broad jump awards for the track team and the city-wide junior boys’ singles tennis championship. After similar athletic success at Pasadena Junior College, Jackie Robinson transferred to UCLA. And that’s where America first saw Jackie Robinson—on stadium fields wearing the university’s colors.

In 1940 and 1941, UCLA’s Jackie Robinson was probably the most versatile and accomplished college athlete in America. Baseball was actually his worst sport: He batted just .097 during the 1940 UCLA season, though reportedly a brilliant defensive shortstop (he’d have to be to stay in the game batting just .097). Jackie Robinson Stadium on the UCLA campus is probably named for the history-making major league baseball player that Jackie Robinson became, not the weak-hitting player he was in Westwood.

Playing Bruins baseball caused him to miss most of the 1940 track season, but he still managed to win a national collegiate long jump title with a leap of 24 feet, 10 and ¼ inches.

Jackie Robinson, Woody Strode, and Kenny Washington played in the backfield of the country’s most conspicuously integrated major college football team in 1940. Robinson led the nation in punt return average (21 yards) and led UCLA in rushing, passing, scoring, and total offense.

(For all their talent, the Bruins could do no better than a 0-0 tie against USC that year. After World War II, Washington and Strode would write their own integration story into history by breaking football’s unofficial color barrier in 1946 for the Los Angeles Rams—a year before Robinson took the field in Brooklyn.)

Robinson also excelled at basketball. He played forward while leading the Pacific Coast Conference Southern Division in scoring in 1940 and 1941. John Isaacs, who played for a trailblazing black barnstorming team called the New York Renaissance, saw Robinson lead a fast-break attack—different than the more studied and deliberate East Coast offenses—and recalled, “The first player I ever saw dunking as part of his game was Jackie Robinson.”

The Chicago Defender, perhaps the nation’s most prominent African-American newspaper of the time, reported, “Scoring is the least of the dusky marvel’s accomplishment.” (That’s how newspapers, black and white, spoke in the 1940s.) “A lightning dribbler and glue-fingered ball handler, his terrific speed makes it impossible for one man to hold him in check.”

So when Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey surrounded himself with scouting reports to choose the man he would suit up and send to break down the color bar in major league baseball, Jackie Robinson’s two years at UCLA conferred a lot of assets. Because of UCLA, he had played sports at the major college level and excelled. He had played alongside and won the admiration of white teammates and fans. He had learned how to cope with the questions and attentions of sportswriters. Integrating major league baseball would be an incomparable test of any man’s endurance and character. But Rickey knew that Robinson had already played—and superbly—under the glare of national attention.

For Robinson, UCLA held even deeper meaning that the professional and sporting preparation he did there. It was on the campus that Jackie Robinson, a senior and BMOC, had met Rachel Isum, a freshman who was studying for her BSN (Bachelor of Science in Nursing).

She was smart, funny, startlingly attractive, spirited and wise (and still is). Robinson started talking about marriage in their student days. She accepted his proposal in … well, a New York second. But she said she needed to finish school. He said he needed to be able to support her. Then World War II intervened, and then the minor leagues, and suddenly the engagement had lasted five years.

When Rickey first met Robinson in his office, he asked, “Do you have a girl, Jackie?”

“I think so,” was Robinson’s reply.

“The love of the right girl is so important,” Mr. Rickey told him, and told him truly.

They were married before Robinson went to that first spring training, and together confronted the insults and epithets. UCLA’s Rachel Robinson would give her husband strength, solace, and wisdom during their trials (and it really was their trials). She has embodied and enlarged Jackie Robinson’s legacy of courage and justice in the 65 years that have followed the path they so bravely forged.

Send A Letter To the Editors