Water has always been a contentious issue in local communities. But now we’re on the cusp of a global water crisis. What can be done around California and the world—by individuals, by governments, and by markets—to encourage us to consume less, conserve more, and avert shortages and other disasters? That’s what scientists, journalists, and water managers came together to discuss at a Zócalo/Occidental College conference at the Pacific Design Center.

When Water Kills

“So here’s my question,” said Occidental College historian Thaddeus Russell, launching into “When Water Kills,” the first panel of the day. “Was Malthus correct?”

Russell pointed out that Englishman Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) predicted that with an exponentially growing number of human beings, insufficient food supply would eventually lead to famine and war. With roughly 2 billion human beings lacking regular access to a clean drinking supply, could one not say that the time of Malthus has arrived, except with water?

“Not yet,” said panelist Robert Lempert, a senior scientist with the RAND Corporation, although he admitted that water “demand is growing way faster than supply.” But there are peaceful solutions to our water problems, Lempert said. Curtailing the birth rate does not have to be the place to start.

Taking a grimmer view was James S. Famiglietti, director of the UC Center for Hydrologic Modeling. “I think Malthus was correct,” said Famiglietti. “I think we’re already at that point.”

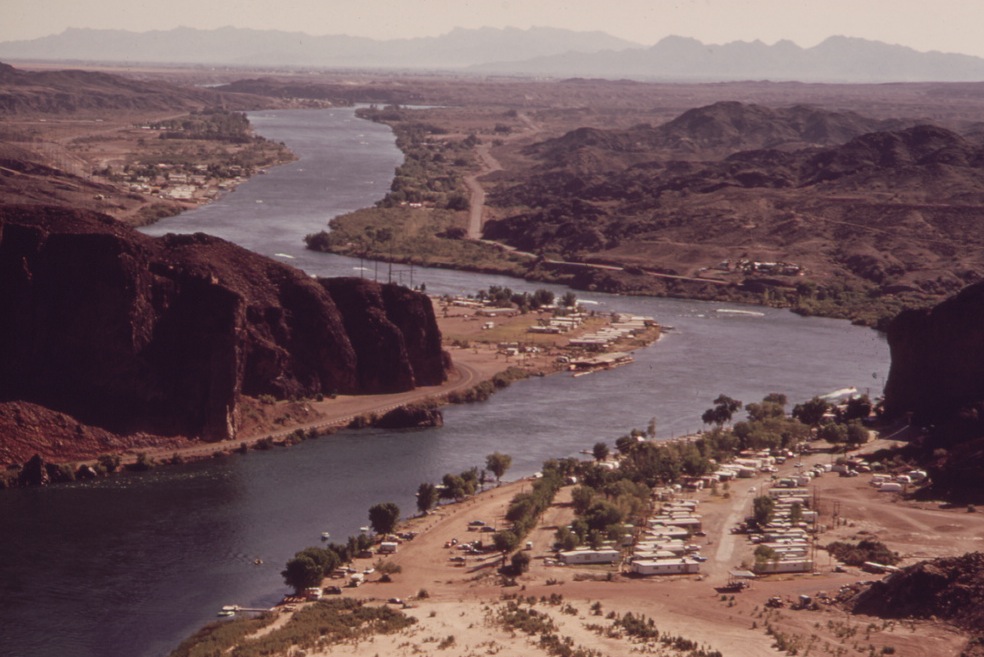

Regionally, water is scarce; some places in Texas are already totally out of water. In Southern California, about a third of the water is local, from aquifers, and the rest comes from outside sources: the Colorado River Aqueduct, the Los Angeles Aqueduct, and the State Water Project. When people look to new local sources, they often talk up desalinization, but that is expensive and energy-consuming. “The first step has to be conservation and efficiencies,” said Famiglietti.

Climate change, which causes the drier places to get drier and the wetter places to get wetter, is complicating the search for solutions everywhere, including Southern California. Snowfall has been in decline. Making matter worse, people are drilling wells and using up groundwater.

Panelist Gretchen North, an Occidental College biologist, noted that a shortage of water has spillover effects. “The Rim Fire”—the quarter-million-acre fire that broke out this August in Yosemite—“would not have been so bad had the forest had a normal moisture content,” North said, noting that our housing construction has not gotten sufficiently prudent in response. “We see people building lovely homes right up against vegetation that is quite flammable.”

Russell observed that water prompts a lot of moralizing, with people made to feel guilty for having lawns or taking long showers. But, given that about 70 percent of water use is devoted to agriculture, what about focusing on larger institutions?

Lempert said that larger institutions are important, too, but “consumers need to be part of the equation.”

North agreed. “I think education can work,” she said. “I would have a push toward eliminating lawns.”

Lempert pointed out that a lot of our problems would probably go away if people were made to pay for their water according to what it really costs. But voters won’t stand for it. He referred to a question posed to him by one politician: “Once we are panicked enough to rationalize the system, will we have enough time do it?”

Russell concluded by asking the panelists to play God and set water policy. (No panelist, it should be noted, took advantage of God status simply to create a lot more freshwater for humans.)

Famiglietti said that one of the most important areas on which to focus is conservation of groundwater, which is currently like a bank account that’s being drawn down without anyone noticing or replenishing it.

Regardless of the solutions they offered, the panelists were in basic, if wary, agreement on one point: To fix our water struggles, more government regulation and centralization of water policy is required at both at the state and national levels.

How Much Should Water Cost?

To open up a panel on the cost of water, moderator Joe Mathews, California editor of Zócalo Public Square, quoted Adam Smith, author of The Wealth of Nations, on the water-diamond problem: Water is indispensable—but really cheap. Diamonds, by contrast, are mostly useless—but very expensive. The fundamental question at a time of scarcity: What should water cost?

“Water—for the first time—is really, truly scarce, and the price is going up,” said panelist Steven Solomon, author of Water: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power, and Civilization.

Mathews asked Jason Peltier, chief deputy manager of the Westlands Water District, which provides water for 600,000 acres on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley, about the impact of water reductions on growers and farmers in California. The water supply has been disrupted by 40-60 percent, said Peltier, and environmental laws like the Endangered Species Act have had a tremendous impact on farmers.

“Water is much more expensive than it ever was,” said Peltier. In the past, water cost Westlands growers $25 per acre-foot; now it costs anywhere from $150 to $800 per acre-foot.

With the 100th anniversary of the Los Angeles Aqueduct fast approaching, Mathews asked Emily Green, publisher of the website Chance of Rain, about the costs to L.A. ratepayers. A major complaint of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, noted Green, is that the huge amount of water used to suppress dust pollution in the Owens Valley results in a 15-percent increase in the average bill paid by Angelenos. “I look at that and say that’s not actually that high,” she said.

Peter Culp, an environmental attorney based in Arizona, explained that water scarcity is also severe in the Colorado River. “The river is a great indicator of the fact that we’ve transitioned from an era of surplus to scarcity,” said Culp. The Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study, completed last year, found that in 50 years “we’ll be short 20 percent” in terms of what the river can deliver in relation to demand—“maybe more, depending on climate change.”

This has major implications for California, which uses 30 percent of the Colorado River’s total supply.

As for next steps, Green suggested that an important element of managing the local water supply involves maintaining a “water ethic” so that people know where their water comes from.

In closing the discussion, Solomon noted one major improvement. From 1900 to 1975, Americans have increased their water use three times faster than population growth. Since then, our per capita water use held steady as our population has increased by 30 percent. We’re drawing less water than we did in 1975. Some of that has to do with regulation, and some of that has to do with cost.

Learning to Live With (Less) Water

The final panel of the day asked what Californians, and the institutions that govern us, can do to decrease our consumption and usage of water.

Reason science correspondent Ronald Bailey said that our water crisis “is a crisis of governance.” The solution, he said, is twofold: to eliminate all water subsidies and all farmer subsidies, and to allocate water rights to individuals rather than governments. “There’s no reason to subsidize any crops at all,” he said. “We have plenty of food.” And when it comes to any natural resource, when it’s left in the hands of the government—or the people, in the case of California—it gets abused and polluted. “You need granular owners who own the water that goes through their land, and they’re able to control it,” he said.

But, said moderator Bettina Boxall, water and environmental reporter for the Los Angeles Times, most Californians live far from the source of their water. They rely on elaborate state-run systems of conveyance to get that water from one place to another. So how independent can Southern Californians really be?

We’re much less dependent on imported water today than we were a few decades ago, said panelist Richard W. Atwater, currently executive director of the Southern California Water Committee. The city of Los Angeles has added 1.5 million people since 1990, but we still use the same amount of water. However, it’s not possible to eliminate Colorado River and Northern California water supplies. It would be “horrendously expensive” to pump desalinated seawater inland from the coast. The desalination facility being built off of Carlsbad is supposed to cost $1 billion, and it meets only 1 percent of the water needs of the people it’s serving, he said.

Panelist Chris Austin, publisher of the policy website Maven’s Notebook, added that our infrastructure also makes it difficult to bring water from the Pacific Ocean inland because it’s built to push water from the inland to the coast. Reversing the way our pipes are built would be incredibly expensive.

The vast majority of human water use in California, and around the world, is for agriculture. Yet, said Boxall, a lot of our conservation efforts focus on urban individual use. What’s the best way for state regulators to reduce the amount of water used by agriculture?

Bailey pointed again to eliminating subsidies. But Atwater said that subsidies are well established, and Austin said that for farming communities, changing from one crop to another is difficult. A rice paddy in the Northern Sacramento Valley, for instance, isn’t suitable for growing something else. And that rice, like most crops in California, is subsidized, Austin said.

“You subsidize the water and you subsidize the crop?” countered Bailey. “That’s very smart!”

Boxall asked the panel what water use in California is going to look like 100 years from now.

Atwater predicted, based on looking at the past 30 years in trends, that we will continue to become more efficient and that our per capita consumption will be about half of what it is today.

Austin concurred, saying that outdoor landscaping is where she thinks we’re going to make the biggest strides. You shouldn’t feel guilty if you have and use grass and are willing to pay to water it, she said. But there’s tons of grass that we don’t use—in our front yards, next to housing development entrances, alongside busy streets, and in highway medians—that could and should be eliminated.

Bailey thinks there’s going to be a lot less agriculture in California and around the world; researchers at Rockefeller University have argued that we’ve already achieved peak farmland, and the amount of land we farm is going to drop, especially as farming becomes more efficient.

Ultimately, asked Boxall, isn’t escalating water costs the best way to get people to change their habits?

Yes, said all three panelists.

Send A Letter To the Editors