Not to pick on Sarah Palin, but it’s troubling for all Americans when there are rumors that a vice presidential candidate thinks Africa is a country, not a continent. Africa is a blurry image in the mind of many Americans—warring, impoverished, unfixable. But then there are the stories of Africa the West doesn’t hear about: urban farmers feeding their families on unclaimed plots of land, a nonprofit building mapping apps to combat election fraud and violence, the booming Nigerian “Nollywood” producing blockbuster movies. In advance of the Zócalo event “Can Homegrown Innovation Change Africa?”, we asked observers of Africa to tell us what they think Americans would be most surprised to know about the continent today.

My undergraduate students are always shocked to find out that the indie rock musician Dave Matthews was born and raised in South Africa. They have no idea that the ESPN reporter, Sal Masekela, is the son of famed South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela. While these students are media-savvy, tech-savvy, and by no means isolated, they, like much of America, are surprised to learn about the African roots of many American cultural phenomena.

Let’s take the case of J.R.R. Tolkien, born in Bloemfontein, South Africa. Some of the famous symbolism in The Lord of the Rings book and movie trilogy come straight out of South African history. Fans of the dwarves will know, for example, that the sun shone down through Moria onto Balin’s tomb—like the sun streams through the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria, South Africa, every December 16—onto a slab dedicated to the remembrance of the “day of the vow” when Afrikaners slaughtered Zulu fighters in 1838 at the Battle of Blood River. It’s a centerpiece of Afrikaner history.

In The Return of the King, signal beacons, calling for aid, are lit along the mountain tops between Rohan and Gondor—as “freedom fires” were also lit along the hilltops of the Orange Free State by Afrikaner adherents of the Ossewabrandwag, a fascist organization in the 1940s.

My students were raised on the Disney movie The Lion King as if it were mother’s milk. They have no idea that the “Wee-mo-way” song was written by a South African artist, Solomon Linda. They love to listen to a 1940s recording of the song on YouTube and compare it to the one they know so well. Linda’s family fought a long, hard struggle for royalties for the song.

African innovation is, and has been, all around us.

Teresa Barnes is an associate professor of history and gender/women’s studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

The past three decades have been marked by a remarkable surge in the popularity of Pentecostal Christianity across many parts of sub-Saharan Africa. This surge is part of a larger trend in which the majority of the world’s Christians now live in the global south. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life reports that, compared to the 9 million Christians in Africa in 1910, there were 516 million Christians by 2010, a 60-fold increase!

Today, there are more Anglicans in Nigeria than there are in England, and the United States is the only country with more Protestants than Nigeria. Historically, much of the evangelizing that took place in 19th and 20th century sub-Saharan Africa was conducted by countless, unknown Africans rather than their more famous European counterparts. And many Africans who encountered missionary Christianity sought to make it theirs by replacing European liturgy, language, and practice with African alternatives. Which brings us back to the ongoing Pentecostal wave in sub-Saharan Africa.

Africans’ interest in Pentecostalism was fueled by literature emanating from North America in the 1970s and ’80s. But, as one example of how they re-shaped Pentecostal theology to be more responsive to local practitioners’ material conditions, they presented a God who is deeply invested in believers’ fiscal and physical well-being in the present, not just the fate of their souls in the after-life. Amidst the swirling political and economic crises of the postcolonial state, this was an immensely attractive proposition.

Conceiving themselves as part of a global religious community, they began to export their brand of Christianity around the globe. As a result, we find that the largest single congregation in Europe, the 25,000-member Embassy of God, is a Pentecostal church founded by a Nigerian man. Today the largest African Pentecostal organizations are sending so-called “reverse-missionaries” to North America and Europe. One of those groups, the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), founded in Nigeria, has 15,000 parishes around the globe including at least one in every major North American city. (Google your city and RCCG). This shift inevitably demands a change in how we, in both secular and religious America, understand our relationship to African Christians and Christianity as a whole.

Adedamola Osinulu is an assistant professor of Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan and a postdoctoral scholar with the Michigan Society of Fellows. He holds a doctorate in culture and performance from the UCLA department of world arts and cultures.

When the British were booted out of Nigeria in 1960, they left behind a fat inheritance of social and psychological trauma. In the years that followed, my mother’s generation—the ambitious, the frustrated, the desperate—left Nigeria by the millions to work and to go to school in the West, believing that their own country and continent had nothing to offer, that the future in Africa was born dead, that the West had a patent on progress.

What’s so exciting about Africa’s homegrown innovation (and, honestly, what’s the alternative to cultivating homegrown African innovation—outside innovation?—500 years of data tell us that hasn’t really worked out well) is that it reveals a generation of young Africans who don’t see the West as a unique symbol of authority, power, and progress. This means something. If we limit the conversation about Africa’s development to governments and NGOs, we miss a bigger point: that a new generation of Africans is shrugging off the psychological humiliation of colonialism and leading the charge to positively change their own communities.

There’s a real connection between national psyche and national progress. Our national fairytale—the American Dream, the belief that anyone can be and do anything—fuels our drive to innovate. This country is home to millions of people who believe they can do something no one else has done, or that they can do the things others have done but do them better; this phenomena requires a confidence that is irrational, artificial, and national. The idea of the American Dream supplies that confidence.

What Americans need to understand is that colonialism systematically stole that kind of confidence from multiple generations of Africans. Today’s innovators show us that young Africans from all over the continent are reclaiming it.

Lanre Akinsiku is a Nigerian-American traveler and writer. He is currently pursuing a master’s in fine arts in fiction at Cornell University.

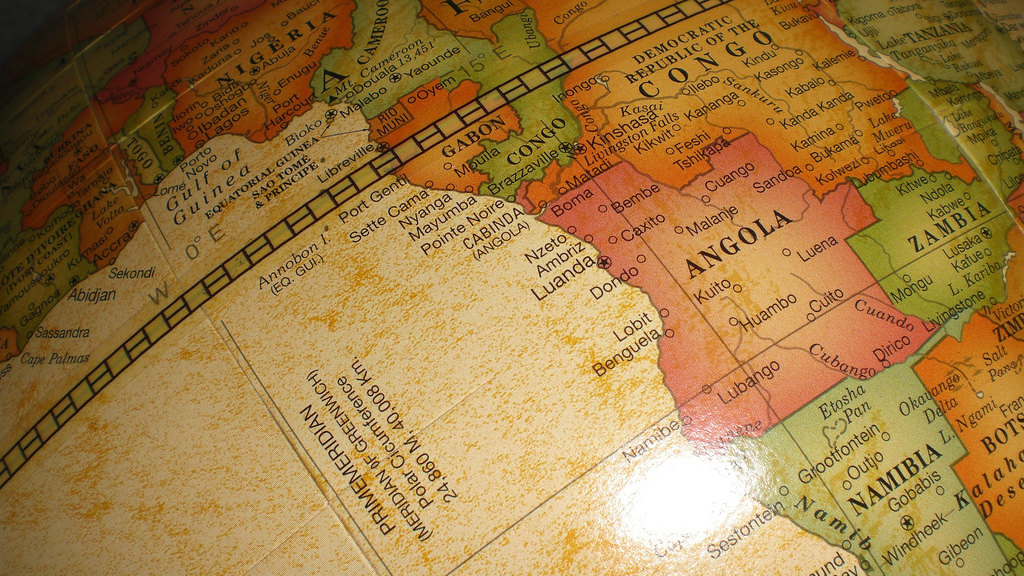

Americans often think Africans are always trying to catch up to the West. This couldn’t be further from the truth. When I went to do dissertation research in Luanda, Angola, in 1999 I bought my first cell phone there. Cell phones existed in the U.S., but I barely knew anyone who had one. In Luanda, cell phones were already commonly available and used among a broad sector of Angolan society.

Similar dynamics exist in music and fashion. Men and women living in Luanda and other cities in Angola in the 1930s and 1940s listened to music from Latin America—plenas, rumbas, merengues—what they referred to as “GVs” (because they came on record albums with each musical number printed and preceded by the letters “GV” from the British company HMV). People all over the world—in the neighboring Belgian Congo, in Senegal, in England, and in the U.S. (including my grandfather in the little town of Dundee, Illinois)—listened and danced to this music in those same decades.

In the 1970s when low-waisted bell bottoms hit the runways, and then the streets of the U.S. and Europe, they caught on elsewhere. Luandan musicians, keen to out-dress their frumpy colonial rulers, commissioned their tailors to copy these styles. Record albums from the period attest to their sartorial panache but the sounds on them deny any simple reading of this as mimicry of the West. Instead, they folded these styles into their own way of doing and being.

So it doesn’t surprise me to find videos of Pharell Williams’ “Happy” uploaded from Benin and Madagascar. And I am always shocked, though delighted, when I hear Angolan kuduro on my university’s radio station, because what young Angolans produce now, young Americans ought to listen to too.

Marissa Moorman is associate professor of African history at Indiana University and an affiliate in the School for Global and International Studies and the program for African studies. She is the author of Intonations: a Social History of Music and Nation in Late Colonial Luanda, Angola 1945-Recent Times. She blogs at Africasacountry.com, and tweets @mjmoorman.