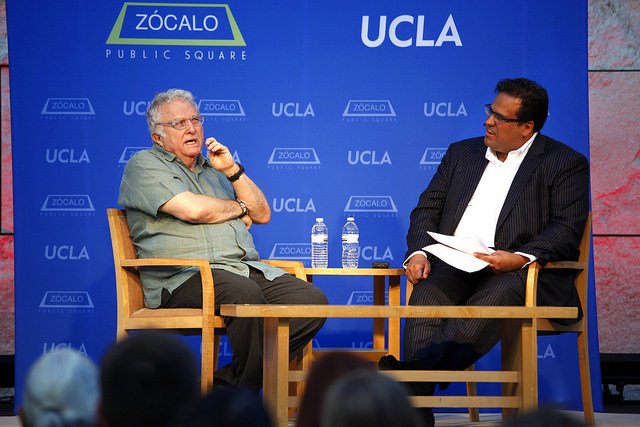

Randy Newman once told Playboy that although he’s not a confessional artist, he thinks people can still tell what he’s like from his work—despite the multitude of subjects he tackles and voices he takes on. But who is Randy Newman as a man? What’s in his head? And is he a product of Los Angeles? In a wide-ranging “Thinking L.A.” event with Newman that was co-presented by UCLA, Zócalo publisher and founder Gregory Rodriguez asked the songwriter to talk about his L.A. childhood, how he creates his characters, and the role of place in his work.

Newman told the standing-room-only crowd at the Getty Museum that Los Angeles has influenced him in a number of ways both obvious—film music is part of his family, and “the sound of the orchestra was in my head at an early age”—and less so: I like the “aggressive ignorance, the sort of proud ignorance of the city,” he said. “There’s a little bit of it in ‘I Love L.A.’” The streets he chose for the song all run east-west: “They’re not garden streets,” he said—but driving down Imperial Highway with a blonde is still pretty good. “I like it here,” he added. “I could go to another place, but I wouldn’t know where.”

Newman is a longtime Westsider. He attended Paul Revere Junior High School in Brentwood, and said that he’s “going to die 400 yards from where I was 5 years old.” The Los Angeles of his childhood “was dusty. They had incinerators in the backyard. The air was worse.” But it was also “wide open.” A friend of his mother’s was in the avocado business briefly, and Newman worked on the harvest a few times, holding out a bag to catch the fruit. “It was the only job other than music I ever had: avocado farmer,” he said.

Newman went on to UCLA, where, he recalled, “It was really hard to find a parking place. And I was disorganized.” He didn’t graduate.

Do you, asked Rodriguez, consider yourself an L.A. artist?

“No,” he said.

But when pressed, Newman admitted that the freedom of L.A. might have had something to do with the way he’s chosen to work and the career he’s had. “New York could have been stultifying,” he said. “There’s all the weight of the European tradition.”

The South also has played a role—and even been a character—in Newman’s music. “You once referred to yourself as half-Southern,” said Rodriguez.

The South is “another country—and getting more so, really,” said Newman, whose mother was from New Orleans. As a child, he spent his summers there, and he still has family in Louisiana.

He noted that he has affection for the South, but not for its racism and ideology. The song “Rednecks”, for instance, is in part about how the North doesn’t have the right to assume superiority over the South.

Newman’s characters are often bad or twisted people.

“Everybody’s human. Everybody,” he said. “There’s no monsters. There’s bad people all right. But they’re human.” Newman said that he thinks the audience can recognize that the characters he writes are wrong-headed. Take “Short People” who, he famously sang, “got no reason to live.” “There’s no cabal against short people,” said Newman.

What, asked Rodriguez, is your fascination with this country?

“It’s big,” said Newman, which you notice when you see other places. He recounted reading an almanac as a kid, thinking about what Iowa was like—“a big, flat thing with corn on it.” He said that when he travels he notices how different places are—how Kansas City is different, how every East Coast city is different.

In 1995, Newman wrote a musical based on the classic story of Faust. Why Faust, asked Rodriguez.

“Christianity is the greatest,” said Newman. “It’s got confession in it. And love. It’s a brilliant thing.” I’ve done some good songs about God, he said. Even if Newman himself is not a believer, he said there’s something to the “comfort of thinking you can go somewhere after here. You know, even Monrovia. It’s pretty final, the end.”

But his songs don’t always offer solace. Take “Old Man,” about a son visiting his dying father, which Newman called “the coldest thing I wrote” before reciting a few of the lyrics: “You don’t need anybody, nobody needs you / Don’t cry, old man, don’t cry, everybody dies.”

Newman said that he wanted to write a song where a father raises a son cold—and wants something more than that back, but doesn’t get it in the end. Newman said that his own father asked if it might be about him, but it wasn’t.

Newman said that people often wonder if his songs are about his family, but they’re not only about people he knows. Sometimes his characters are people he hears about—he recounted a story of a family with two drunks, a depressing story, but that’s what he’s interested in.

“You talk about such dark things in such wonderful ways,” said Rodriguez. “You make it accessible to us.”

In the question-and-answer session, audience members asked Newman to talk a bit more about his inspiration.

How do you make these dark stories hopeful—and how do you continue to tackle these difficult characters?

“You have to avoid the maudlin with some fairly rough stuff,” said Newman. “It’s nice if you let the characters speak for themselves.” He said he’s surprised that more songwriters don’t write like short story writers—like John Cheever and John Updike, who take on the voices of others. Fiction writers “are not necessarily in their stories,” Newman said. Songwriting is a more immediate medium. “People want ‘I love you, you love me.’ It just took me a long time to figure that out,” he said.

Send A Letter To the Editors