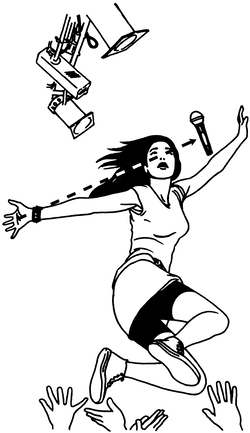

In high school, instead of calling the study of motion and energy “Basic Physics,” I propose we call it “Advanced Tactics for Rock Stars and Secret Agents.” To kick off the course, the teacher could, with the students clumped together to catch her, perform a gorgeous stage dive with a midair twist and microphone toss-and-catch from her desk. She would demonstrate that gravity treats all masses equally by showing that the velocities of her body and the microphone will be perfectly matched during the fall, each accelerating 9.8 meters per second every second. The students would then be graded on their own stage-dive-and-microphone-toss combinations. They could earn extra credit for a pre-jump slide across the desk after estimating the coefficient of friction between their shoes and the top of the desk.

Lessons could follow on how to tame feedback from a microphone set next to a speaker, which occurs because the speaker is endlessly amplifying the height of the sound waves without changing the space between them. The aspiring secret agents in the class could memorize and test a few simple steps to use Newton’s laws of motion to win fistfights on moving trains (after signing a waiver, of course): Face the front of the train. When the train turns left, kick your opponent to your right. Since his body wants to continue in a straight line, he only needs a nudge to tumble off the train.

Lessons could follow on how to tame feedback from a microphone set next to a speaker, which occurs because the speaker is endlessly amplifying the height of the sound waves without changing the space between them. The aspiring secret agents in the class could memorize and test a few simple steps to use Newton’s laws of motion to win fistfights on moving trains (after signing a waiver, of course): Face the front of the train. When the train turns left, kick your opponent to your right. Since his body wants to continue in a straight line, he only needs a nudge to tumble off the train.

Physics is sexy. Understanding it puts you firmly in charge. And what teenager isn’t hankering for this kind of appeal and control? Apparently, plenty of teenagers—at least when it comes to understanding physics. Maybe we adults are not communicating the benefits of physics well enough to American teens. Fifteen-year-olds in the U.S. are 21st in science test scores among 34 developed nations, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s 2012 Program for International Student Assessment. To find the U.S. on the results, you need to scan down past Canada, Ireland, Italy, and Vietnam. We need only to look at the history of food production, disease control, power generation, and defense to understand that if we continue to be a nation of fashion majors we could be in serious trouble. We need more high school students to take physics and fall in love with it so they might study biomedical engineering and alternative fuel production in college.

I am a mechanical engineer now, but as an eighth grader in Anchorage, Alaska, I was determined to be a cool kid rather than a smart kid. I worked very hard to get bad grades and smoke non-filtered Camels without heaving. When my stepfather noticed that his cigarettes were missing and that I’d dropped out of the accelerated math class, he had a talk with me. He told me that being smart was my ticket to a better income and more freedom than he had as a mechanic. As he pulled metal slivers from his diesel-stained hands after dinner one night, he laid it out for me clearly: He and my mom would only help with college if I majored in something practical that would get me a job right away. He said that not going to college meant I would likely work for someone not as smart as me, making coffee or filling out long reports that no one would read. I didn’t want that. I didn’t want to be anyone’s assistant. I wanted to be a big deal. I wanted to make my own decisions. I also wanted to have a motorcycle, several guitars, and learn to cliff dive. Between my stepfather’s nudging and a high school physics teacher who created story problems with puppy-saving helicopter rescues and space-exploring time travelers, I decided I would be an engineer.

In college I studied chemistry, physics, thermodynamics, fluids, vibrations, and materials. Those subjects sound dry, but they weren’t. I found a beautiful order in energy, gravity, and even entropy. I was learning how to read every atomic twitch of the universe. I was deep into her diary, and it was as thrilling as any cliff dive.

Even more surprising, I found the laws of physics applied to my personal life. Covalent and ionic bonding helped me understand that different atoms, like people, have their own particular ways of bonding. Sometimes they share their outer shell of electrons; sometimes they are stuck together only by magnetic attraction.

I applied physics to my personal decisions. I learned how to think through problems, how to accept reality, and work with the facts. The laws of motion clearly implied that changing direction wasn’t easy once you had some momentum. In college I played bass in a local band, but I was careful to point my vectors toward finishing my engineering degree. I didn’t want to start anything I would have to quit later—smoking, drinking, a whirlwind romance with the much older guy running the sound system for our band. I avoided any momentum in those directions.

I learned not just how to take risks, but how to take calculated risks. A stage dive or jumping your car over a separating drawbridge might look dangerous, but if I’ve done the math and practiced the technique, I can execute each with confidence. The laws of motion and energy will never change, so I will never be surprised.

My stepfather was right: Engineering gave me the exciting life I wanted. I manage design and construction of huge commercial projects filled with colorful characters and high drama. And I am a local rock star—playing bass in the Portland band Swan Sovereign.

Perhaps if an ultimate fighting champion came to class to demonstrate an effective cobra clutch, and the teacher asked students to create free body diagrams showing how force and torque can stress a body, one of them might become the biomedical engineer who helps people with spinal injuries get out of their wheelchairs and walk. Maybe if we explained in class how to escape a sinking car without losing a favorite pair of shoes, a student would be inspired to harness fluid pressure and create the next generation of turbines and update our power grid.

No matter what these students become, this kind of learning would provide them with the chance to fall in love with the universe as I did. And if they do, they will find that the laws of physics are steady but constantly surprising, like any true love or great rock song.

Send A Letter To the Editors