There’s something about agriculture that grows the soul.

Fortunately, I could see the strawberry and lettuce fields of the Salinas Valley from the window of my eighth grade English class. There were colors, all types of bugs, machines, migrant workers, and the sun. The clouds above sang the softness of a city, and the mellow sound of the strawberry pickers’ work songs taught me how to pray. The songs seeped through the classroom, with moans and repetitive refrains mixed in. Even watched from indoors, the fields were both beautiful and interesting because they represented so much to so many people in Salinas—history, pain, and hope.

When I was young I lived the city’s divisions: the haves and the have-nots. The south side of Salinas housed the historical places like the National Steinbeck Center, City Hall, and Salinas High School. North Salinas, where I lived, was business central, and we walked the hallways of Northridge Mall and reveled in the crisp lettuce fields along the freeways. The east side, where it all went down, housed many migrant workers and became the home for gang violence.

“And the little screaming fact that sounds through all history: repression works only to strengthen and knit the repressed.” – John Steinbeck

As I came to understand that Salinas was known around the world for literature as much as for lettuce, my concept of self began to evolve. I saw John Steinbeck’s early life in Salinas as a call to action. Why couldn’t young people in Salinas continue the tradition of writing creatively? Why couldn’t I? The honesty within The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden sets Steinbeck apart. He wrote, rather radically, about the smell of sun-roasted garlic and artichokes, and about what was rotten in Salinas, too.

His books meshed with my own experiences and shaped my consciousness. My mother, Valerie, was the president of the local NAACP chapter, and her fight for civil rights was just as influential as Of Mice and Men. She marched the streets of Salinas, took companies to task that were guilty of discrimination, and promoted a sense of racial pride for community members. The work she did was coupled in my mind with my father’s dedication to the juvenile justice system. His 30 years of service to the Monterey County Probation Department gave community youths a fresh start and support for their families. While my parents organized brilliant community work, our family faced quite a bit of opposition.

“To be alive at all is to have scars.” – John Steinbeck

My parents’ activism made our family a target. There were threatening calls, stares when we were out in public, and there were times when access was limited because my parents were unwilling to back down from community issues. I have a word to describe these moments—scars. Steinbeck’s philosophy that scars are the threads that keep us living sat with me for quite a while growing up. The scars were just as deep in Salinas as the ditches beside the rows of lettuce.

But if you were to drive up into the back hills of Salinas today, you’d find my mom and dad looking over the city they cherished so much. My parents stayed in Salinas, hopefully, because they realized that the weather is perfect and the produce is unimaginably crisp – and because their 30-plus years of activism and mentoring charged them to stay.

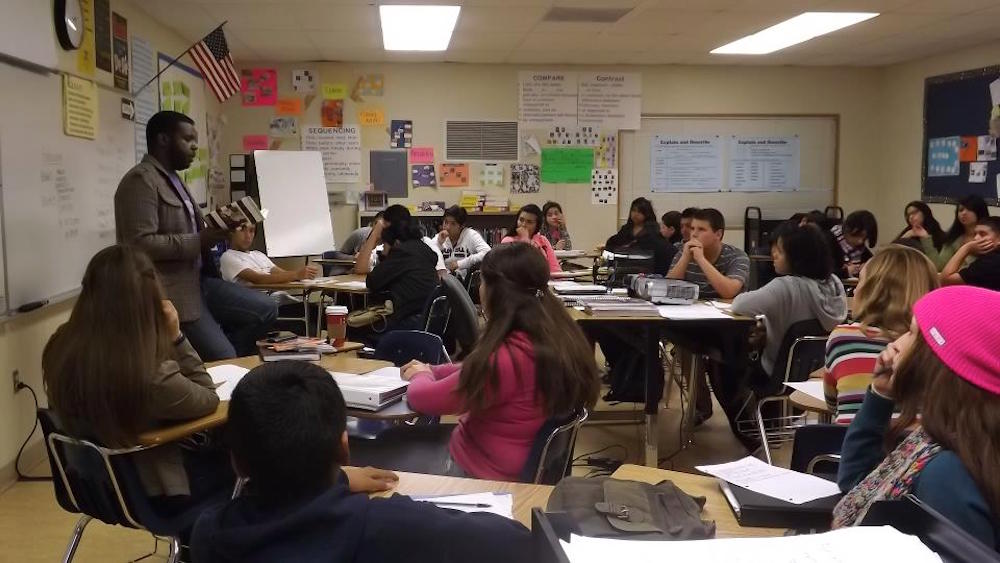

I started writing poetry as a high school senior in Elizabeth Birkeland’s AP English class mostly with them in mind. I thought about how my parents were so concerned about the state of the community, and how they took action where needed. This drove me to think about our larger communities. Poetry became my voice to the world. At first poems were opportunities to share the troubles of being a black man in America. But, after I became a bona-fide recognized poet, I knew I wanted to give back, which meant writing about Salinas.

It would be a weighty mistake for me to act as if the violence in Salinas hasn’t been a major community scar. I lost many comrades in high school to futile gang violence, and eventually went to work with former mayor Anna Caballero to alleviate gang tensions through her non-profit organization Partners For Peace. The work we did together fostered the idea that our scars could indeed heal. We were healing the hearts of our community members.

“A man without words is a man without thought.” – John Steinbeck

East of Eden, my favorite Steinbeck novel, was his ode to Salinas. He sought to display the sights and sounds of early Salinas. It did something else for me the first time I read it back in the eighth grade—it taught me to love a city with a difficult historical trajectory. Cathy’s character in the book went down to work in Salinas’ most famous brothel, and she helped Steinbeck to expound upon the dark side of the city. For me, the dark side was found in relation to the inequities, the racial profiling, and gang warfare on the east side.

But the good within the city always outshined the evil. Certainly, Salinas’ greatest contribution to the world has been lettuce. Steinbeck wrote extensively in East of Eden about lettuce and how it was shipped around the world—fresh, green, crisp things. For Salinas, lettuce is Hollywood, Disneyland, oil, and factories all in one. It is livelihood, but it is also a metaphor for the life within such an agricultural and artful place.

When I was offered the opportunity to serve as the inaugural poet laureate for Salinas I found the honor breathtakingly ironic. Even though I’d written four books of poetry, as a young black man, I felt that a city with such racial ambiguity would likely have chosen a poet who looked more like John Steinbeck. But part of Steinbeck’s legacy was showing that Salinas looks remarkably different for everyone. There were people who owned the fields, those who tended them, and those, like me, who were inspired by them.

This made John Steinbeck a revolutionary writer. He took the sights and sounds of the most beautiful countryside in the world, and placed them in books. Yet, he challenged writers who would follow him to tell the gospel truth, even if it was unpopular in literature. I learned on the touring circuit that these concepts weren’t as easily ingested by those outside of Salinas. His books were sounding boards for local issues, but because of the beautiful terrains that hypnotized readers over and again, the books didn’t connect people strongly enough to the dark side of Salinas. Despite that shortcoming, books like Tortilla Flat, Cannery Row, and Winter of Our Discontent inspired me to write the newest truths of Salinas, to talk about the emergence of a new collective of writers and thinkers, including budding poets Mikey Frias and Eduardo Velasquez.

When I sat down to pen my own ode, Wave to Salinas, the city’s official poem, I immediately thought about the light and dark of the place:

Diamond amid coal cinders,

little city with large expectations,

turns dreams the distance…

Warrior-Vikings plant strawberries

in the soiled sun, dirty

fingernail freedom badges,

tans darker than carbon…

There, the grapes of wrath are stored

in a wine cellar across from

Fresh Express—meeting-place of the

Chavez migrant movement…

At the lettuce cornrows growing in the dust,

have a wave to Salinas for me.

John Steinbeck taught me to write about what’s real. He wrote about his love and hate for Salinas, the city which grew him up like a head of iceberg. His roots are within every poem that I write, as the roots of the Grapes of Wrath are spread throughout the Salinas Valley. He also gave me hope that a young black man from a historically racially divided and class-trapped city, could one day become this city’s poet laureate.

Send A Letter To the Editors