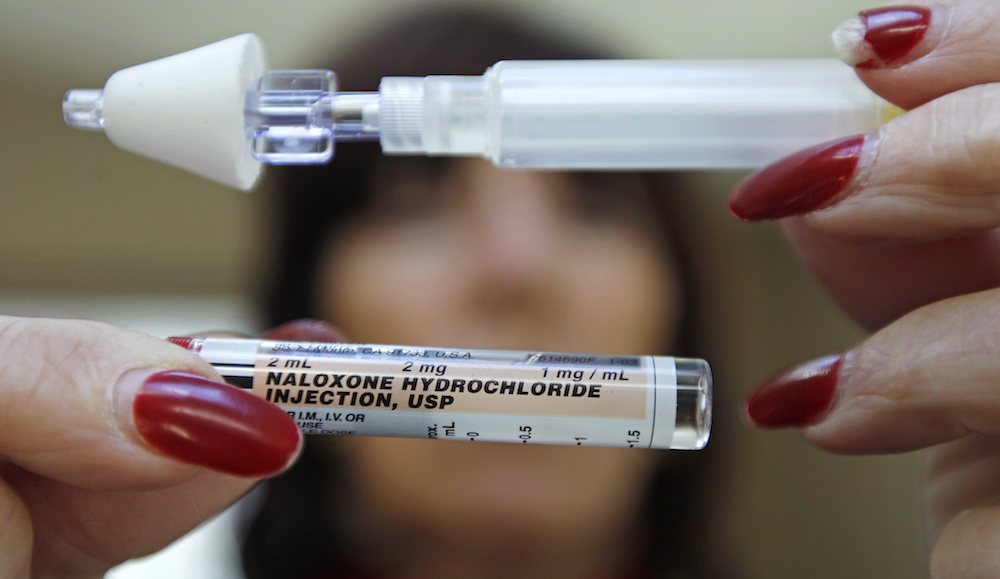

In this Tuesday Feb. 27, 2012 photo, Kathy Deady holds up a tube of Naloxone Hydrochloride, also known as Narcan, in her Quincy, Mass., home. Narcan is a nasal spray used as an antidote for opiate drug overdoses. Deady twice had to use the drug on her son, who was suffering from an overdose of heroin. The drug counteracts the effects of heroin, OxyContin and other powerful painkillers and has been routinely used by ambulance crews and emergency rooms in the U.S. and other countries for decades. But in the past few years, public health officials across the nation have been distributing it free to addicts and their loved ones, as well as to some police and firefighters. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

In August, she drove two miles, past a large hospital, to get her boyfriend to our soup kitchen, but not for the food. She knew someone here would have Narcan, a life-saving overdose-reversing drug that, until recently, was unavailable here in Maine to people at risk of overdosing.

Her boyfriend was bluish and slumped over the passenger side of the van when he arrived. Brittney, a caseworker, administered Narcan and he survived.

Sternal rubs. Rescue breathing. Intra-nasal application of Narcan. These are the lexicon of emergency personnel—people whose job it is to save lives during desperate times. Increasingly, and unexpectedly, these words have also become part of the unofficial job description for me and other social workers at the Preble Street Resource Center in downtown Portland, Maine.

With so many clients at risk of heroin and opiate addiction, we are the new first responders.

We are also the last responders: We’ve had so many clients die that we’ve gotten good at compassionate grief. We’ve become experts at the well-staged memorial service. Two hundred and fifty Mainers reportedly died of heroin and opiate overdoses in 2015, up from 176 in 2013. Over the past six months, we’ve responded to more than a dozen overdoses in our space, and held roughly the same number of memorial services for people we know who died on the street.

I began my career as a social worker with high ideals. Fresh out of Africa and the Peace Corps in the late 1980s, I wanted to apply “practical idealism” to alleviate the suffering of others, especially homeless people. I started working in a New York City children’s shelter in the South Bronx, moved to running shelters in other cities, and finally came to work in Portland, population 66,000, five years ago. Preble Street is a shelter where people can breathe and find connection, community, and support. We serve 1,100 meals a day and work with 1,200 clients a year. By providing a pair of socks, a shower, and a hot meal, we strive to create meaningful connections with struggling people. We’re guided by our founder Joe Kreisler, who said: “Part of my job, part of being alive, is making sure that other people are, too.”

The high risk of death by heroin and opiates has changed our work—and in a way changed who we are. We’ve had to modify bathrooms that promised a homeless person some modicum of privacy, by cutting 10 inch gaps at the bottom of the doors and installing a light system that lets us know if someone has stopped moving. We didn’t want to do this, but we’ve simply had too many people who stopped breathing in those bathrooms. The pressure we feel as the final stop before someone dies is too real to stick with our ideals about dignity.

In October, we had a woman who—sitting on the toilet, pants around her ankles, needle in neck—was unresponsive and barely breathing. We screamed her name, scraping our knuckles across her sternum. Quick-thinking staff, the overdose response protocol, and another client with Narcan saved her life. Later that week, she came back, embarrassed, sorry for causing us such worry, and said she’d secured a rare bed in a detox unit and was on her way to recovery and a changed life. The near-miss reminded us that dead addicts don’t recover—that’s our mantra these days.

Maybe heroin used to be perceived as an inner city thing, but today, high rates of drug overdoses are occurring in rural and impoverished counties. Nearly 90 percent of people who tried heroin for the first time in the past decade were white, and the highest use rates were among those making less than $20,000 per year.

Maine is poor, rural, and white—and at the epicenter of what we call an “epidemic.” The number of people addicted to heroin nationally has more than doubled in a decade, from 214,000 in 2002 to 517,000 in 2013, according to a study released this year by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. But we do not respond to this epidemic the way we would if, say, the number of measles deaths had more than doubled in the same period. Instead of a medical response, the opiate-heroin epidemic gets a moral one: Calls for more arrests, punishment, shaming, the suggestion that offering Narcan will “just encourage them.”

Scandalously, the cause of our current problem is not a virus but a series of deliberate policies that combined into disaster. Between 1996 and 2002, pharmaceutical companies marketed opiates as safe, long-term pain relievers. By 2010, the United States, with about five per cent of the world’s population, was consuming 99 percent of the world’s hydrocodone (the narcotic in Vicodin), along with 80 percent of the oxycodone (in Percocet and OxyContin). Mainers were prescribed opiates at twice the national rate and soon pain pills were circulating across the state.

When Obamacare began, Maine was the only New England state that did not expand Medicaid, forfeiting more than $300 million in federal funds yearly. Then in January 2013, spending on MaineCare, Maine’s Medicaid program, was reduced and 20,000 low-income Mainers lost coverage. Without Medicaid funding, the number of beds in detox programs fell. Now, in Portland, there are only 10 beds for the uninsured.

For those who couldn’t get off the opiates, heroin arrived, often cut with more potent and cheaper fentanyl. The number of people who died from heroin in Maine rose from 7 in 2010 to more than 70 in 2015. This has created real dilemmas for my colleagues and me.

The day before yesterday a long-time client asked for $4. He knew we would refuse but he was desperate. With his MaineCare cut, he was no longer able to fill his prescription for suboxone—widely used by people trying to kick heroin. His choice? Find $4 to buy some suboxone off the street—or go get some heroin, which his dealer would undoubtedly provide for free, welcoming back an old customer with open arms. We held our breath until we saw him the next day, knowing that there was always the chance that we would never see him again.

We’re watching the gap between public policy and human need grow wider every day.

In 1848, the great German scientist Rudolph Virchow said that medicine is a social science and politics is nothing more than medicine on a grand scale. That has been the case with opiates and heroin. The people caught between these policies and politics need an alternative to death as a way out.

The first step should be to respond to this crisis like a real epidemic, not a moral failing. We do not need a “war” on addiction.

We need, first of all, to make Narcan more readily available. We need more detox beds, obviously, but also programs that employ, house, and support people who’ve come out of detox. And we need rational policies from government, business, and medical leaders that improve the health of everyone. The fact that so many Mainers were prescribed opiates in the first place speaks to deeper issues in our health care system.

The most significant thing we can do is take the federal money to expand Medicaid/MaineCare—almost 70 percent of Mainers agree that this makes sense. This one policy would mean more treatment, and more saved lives. This epidemic is taking place not just at my workplace, but in your community and, increasingly, in your family.

Send A Letter To the Editors