A Rangers hockey game was on TV as I folded the warm pile of laundry splayed out on the couch. It was a brisk, fall Saturday afternoon in the suburban part of Schenectady, upstate New York’s Electric City. I was 12 years old and into hockey back then before the sport became the joke: I went to a fight and a hockey game broke out.

My mother was in the kitchen doing what she characteristically does on a Saturday, making spaghetti sauce, meatballs, sausage, and braciole for the week. The comforting aroma of sautéed garlic, onions, and tomatoes cooking with the frying meat filled the house. I treasured Saturdays for the simple reason that I felt loved.

Two of my older sisters were upstairs in their rooms doing whatever. (Bonnie, the oldest, was away at college.) Being the youngest of four girls, followed later by my brother Tommy, I was never included in their affairs, and pretended not to care much, since they ridiculed me whenever I was with them. And so being downstairs alone with the laundry and the hockey game suited me just fine.

Saturdays, my dad was at his store working. On Sundays, though, Dad and I watched football together. I loved watching sports with my father. It was one of the few times I felt the closeness he and I once shared before my brother was born. Then I became like my sisters; girls with whom he didn’t know how to communicate or show outward signs of affection. But watching football together was our bonding time. Except when he decided to root for teams who were not from New York.

“Get out of the room!”

“What?! Why? New York is winning.” I’d be completely confused.

“Out. Now!” He’d say as his jaw clenched and his finger pointed threateningly at me.

He never explained why he would, at times, change his New York affiliation, but then, he never explained much of anything. He didn’t make sense to me sometimes, my father. Yet on this day, this Saturday, I began to understand who my father was and how to play outside of the rules.

There was an abrupt knock on the family room door. Since my brother’s friends entered through that door, I called out, “Come in,” while keeping my eyes glued to the game and continuing to fold the towels. After a slight beat, there was another knock. This time more forcefully.

“It’s open!” I said with annoyance, not knowing where my brother was or why my brother’s friends suddenly developed a hearing impediment. But again, more knocks.

Irritated, I got up to answer the door. As I swung it open, a gold badge and an identification card with a blurred picture of a man’s face was shoved within millimeters of mine. It was thrust so close to my nose that my eyes couldn’t focus to read what I assumed I was supposed to be reading.

“I’m lieutenant so-and-so of the FBI.”

He was a tall man in a dark suit. “Is your father home?”

Without waiting for a response or an invitation, his arm stretched out several feet like a Gumby toy and brushed me and my pile of towels aside as he entered the family room. When my eyes and mind refocused, I saw three other men standing in the garage. They were the biggest men I had ever seen.

Two were dressed in similar outfits of red plaid flannel shirts, khaki pants, and work boots. The third man behind the intruder wore a dark suit as well. I couldn’t tell what he was thinking, he just followed suit, no pun intended, and entered the house after the man with the badge. The other two men in plaid flannel and khakis walked past me into my family’s home. No one bothered to wait for an invitation.

“Come on in,” I muttered sarcastically under my breath.

Though I did not understand exactly why these four oversized men were in our home looking for my father, I sensed my dad’s odd little nightly rituals had something to do with it.

The author’s father (third from the left), standing behind his mother and with other members of his family in 1941.

My father, Angelo, was a generous man, a self-made man with only a high school education who treasured his family. He was a storyteller, a raconteur, whose charm amused those he enjoyed entertaining.

His mother, Teresa, was an industrious and formidable woman, not unlike the icon from Calcutta. She made things by hand (doilies, handkerchiefs) and started selling small dry goods out of her two-bedroom flat in the Italian section of Schenectady’s Mont Pleasant neighborhood. Business went so well that her husband Carmelo, a mason by trade, built a department store across the street with two apartment dwellings on the second floor. Thus, the family business was established. When my father returned from World War II, he moved into one of the flats upstairs and ran the department store with my grandmother.

The store was successful not only because it provided for the needs of the small immigrant community, but also because my father had a personal touch with his customers. He took great care in measuring a proper fit for their new shoes. He covered their children’s schoolbooks with plastic, provided money order service for those without a bank account, and supplied goods from dresses to toiletries.

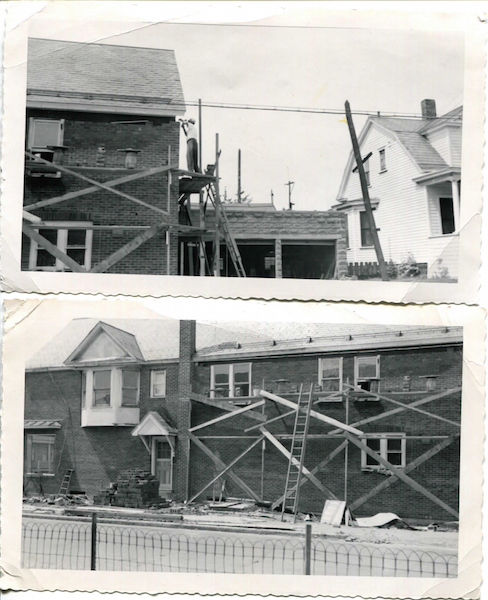

The author’s grandfather, renovating a building so the family could run a department store on the first floor and live on the second.

***

As the four massive men stood looking around the family room, I called for my mother, who was in the kitchen oblivious to the intrusion.

“Ma, these men are here to see Dad.”

My mother came out from the kitchen wiping her hands on the mapine (Italian slang for dishtowel). As she graciously extended her arm with a smile to greet them, the large man in the dark suit said, “Ma’am, I have a warrant for your husband’s arrest.”

My mother’s smiling countenance dropped liked the ball at Times Square, as if a shock went through her body from head to toe. The four giant men then circled her like dogs with their prey. My small, agile body quickly slipped by them unnoticed as I dashed upstairs, knowing that any incriminating evidence they were looking for needed to be found, hidden, and destroyed. What that evidence was exactly I wasn’t certain, but I knew what it looked like, and so did my sisters. We saw it almost every evening after dinner.

Dinner was a nightly ritual. It was my father’s insistence that we eat together as a family, something that I could never understand. It’s not as if he waxed poetic at the dinner table. He just wanted us all there, together. It didn’t occur to me back then that it was probably the only time he saw his family together in one place at one time, given his seven-day work week. For me, it was just another rule by which I had to abide.

When dinner was over, we girls would clean up. My brother was allowed to go off and play. My father remained at the head of the table and took out a brown paper bag or a shoebox from the store, or both. He waited patiently as we wiped the table clean and dried it. Then he’d pour the contents of the shoebox or bag out onto the tabletop.

They were always the same type of items: narrow rolls of paper, the kind taken from a small adding machine, and other individual bits of paper held together by paper clips. He used the paper bag to make his notes, or if it were a shoebox, he’d write on the back of its lid. On these small bits of paper were odd writings—two or three letters with a dash followed by numbers, none of which made sense to me.

“Dad, what are those numbers?” I’d ask.

“Just ‘figgers’,” he’d say with a Brooklyn accent.

My father wasn’t from Brooklyn—his cousins were—and he didn’t normally speak with a Brooklyn accent, but there were certain words he would pronounce as if he were raised in Bensonhurst.

“But what do they mean?”

“Just ‘figgers’,” he’d say, continuing his calculations.

When he finished at the table, he went into the family room with his paper bag or shoebox of “figgers.” He called either a woman named Cathy or his friend, Fiorentino, (a name you couldn’t make up) and spoke what sounded like code into the phone.

“Hey Fior,” his nickname for Fiorentino, “INT-175, FDV-150, ZJH-333.” And so the one-sided conversation went.

When he finished the phone call, he’d typically walk to the fireplace, empty the shoebox or paper bag of all its contents, and light everything on fire. I’d watch with him sometimes as he waited until the papers ignited. The fire didn’t last long and he’d spread the bits of paper around, making sure they were all dark dust.

***

Upstairs my sister Donna was on her bed. She was a senior in high school and president of her sorority, and always had an air of superiority. She shot me an annoyed look as I rushed in.

“The cops are here. Dad’s under arrest!” I blurted.

Donna shot up like a rocket as my sister Elaine, only a year older than I and the one to whom I was closest, rushed into the room.

“It’s that thing he’s been doing,” Donna said.

“What is that thing he’s been doing? I asked.

“You know, those papers.”

“But what are those papers?”

Whether my sisters knew or not, I couldn’t tell. They didn’t answer. But whatever it was my father was doing, even though we knew deep down it was not totally above board, we were going to hide from the men downstairs. Donna went into combat mode.

“Let’s go into Mom and Dad’s room. Search the drawers. Anything you find, those bits of paper, stuff in your panties.”

Like a well-organized sports team, we made a game plan: to strike before the feds ascended the stairs. Time was of the essence and we had to be discrete.

Downstairs the feds kept my mother in close sight. They made sure she had no chance to stash away any convicting proof of my father’s guilt as they scoured through cupboards, drawers, and sofa cushions, unaware all the while that actual evidence tampering was happening one flight above them.

Donna took on my mother’s dresser, Elaine the smaller closet, and I the walk-in closet where many shoes boxes lay on the shelves. I dug through sports jacket after sports jacket, wanting to find something, anything, that would save my father from the wolves downstairs, but there was nothing except paper clips and loose change.

“I found something!” Elaine exclaimed.

Donna and I ran over to her. My heart pounded. Elaine’s hands shook as she held small pieces of yellow paper. Quickly unfolding them, we realized … it was a false alarm. They were store receipts from recent sales.

“Put ’em in your panties anyway—they could be code for something,” Donna ordered. Elaine obeyed.

I peeked out my parents’ bedroom door to see where the feds were. Only their legs and shoes were visible from the top of the stairs as their feet disappeared into the living room. Their next stop would be the second floor.

“They’re getting closer,” I whispered as I rushed back to the closet. I looked around for where to continue my search. The shoeboxes sat on the shelves as if screaming at me. Of course! I ripped open lid after lid as I eagerly expected to find the gold, the treasure, the Ark of the Covenant (though I didn’t actually know what the Ark of the Covenant was)! But instead of finding the evidence and saving my father, all that stared back at me were pairs of high heels, low heels, slip-ons, men’s dress shoes, and loafers. My excitement turned to frustration and all I wanted was for this to end, for the large men downstairs to go away, for my mother to continue making her sauce, and for me go back to folding the laundry and finish watching my hockey game!

The men’s voices downstairs were getting louder. They were now at the bottom of the stairs. I hurried to get the last box on the shelf, accidently knocking another off its ledge. Its contents spilled onto the floor. I froze. There, on the carpet in the middle of my parents’ walk-in closet, were what seemed like millions of little pieces of white paper with the all-too-familiar code on them and a small, dark notebook.

“I found them! I found the ‘figgers’!” I whispered straining not to shout.

My sisters rushed over. The three of us stared at the evidence the feds were coveting strewn over the floor. Now, Donna, Elaine, and I had to figure out what to do with it.

Send A Letter To the Editors