In 1776, on the brink of his first battle with British troops after America declared independence, George Washington gave a spirited defense of breaking from British rule. “The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army,” he told his troops. “Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of a brave resistance, or the most abject submission.”

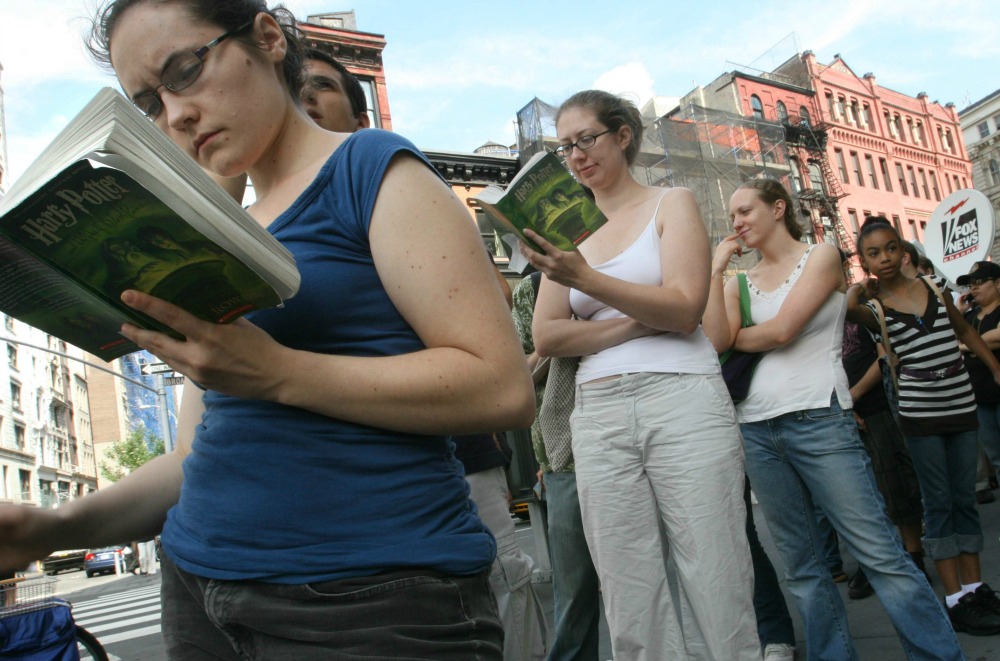

Needless to say, two and a half centuries later, America views British influence on much different terms. No longer the evil oppressor, the British are more than a longstanding political ally; they’re essential to our culture. We built a theme park for Harry Potter, after all. Adele gets us through Thanksgiving. Heck, we even cast a Brit to play Abraham Lincoln.

At the same time, demographically, a much smaller percentage of Americans claim British roots. At the time of Washington’s address, the majority of newly minted Americans were of British descent. Now, the most common countries of origin for America immigrants are China, India, and Mexico, according to a recent study by the Census Bureau.

But what have we inherited from our formerly “cruel and unrelenting enemy” that, for better or worse, we just can’t seem to shake? In advance of a March 9 Smithsonian/Zócalo “What It Means to Be American” event—“Will America Always Be a British Colony?”—we asked five people with expertise on both sides of the pond: What are the most persistent legacies of past British rule—cultural, political, legal, etc.—that have survived and will continue to survive America’s ongoing demographic changes?

One need not be an Anglophile to see that there’s no America we would recognize without British cultural and political influence.

What would the American constitution be without the Magna Carta? Or a respectable spy genre without James Bond? Or a rock and pop scene worth its name without the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Elton John?

What about Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, Kipling’s The Jungle Book, Orwell’s 1984, Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Rowling’s Harry Potter? Is there an American literature—or musical theatre—without these things?

There would be no dancing in America without jigs, no bedtime without “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.” Can anyone imagine American film, if there had been no Alfred Hitchcock, Audrey Hepburn, or Charlie Chaplin?

Our dinner parties would be poorer without Oscar Wilde’s wit to quote; our Christmas less inspired absent Handel’s “Messiah” (a German composer who composed his Oratorio in London). We need our Valentine’s Day (the modern day tradition stemming from Chaucer), our Renaissance festivals. We must have our bulldogs and beagles, our terriers and retrievers and collies and spaniels—all English breeds.

If not for the need to define ourselves against the British, we wouldn’t have that stirring call to arms from Patrick Henry: “Give me liberty, or give me death” (or a “Tea Party” movement today). Nor the circumstance that George Washington apparently spoke with a brogue accent. Or the fact that English today is the global lingua franca.

None of which is to say we ought to resist change and find ourselves longing for an Anglocentric past. After all, Americans look forward. “If we open a quarrel between the past and present, we shall find that we have lost the future,” as Winston Churchill—whom Americans loved enough to declare an honorary U.S. citizen—once put it.

Jeffrey Gedmin is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, a senior fellow at Georgetown University, and a senior adviser at Blue Star Strategies. He lived in London from 2011 to 2014.

What will not change when the demographics do? Place names. There are more than 650 American cities that share their name with those found in the U.K. As British colonists set up home in America, they brought with them the names of their hometowns and cities. Some have argued that this was nostalgia for home and homesickness for the motherland. Others have argued that this was a very pragmatic way for those at home, sending letters and parcels, to remember the addresses of those who had crossed the Atlantic.

So whether it is Birmingham, Alabama, which once readily accepted that other shameful export from Britain—slaves—and became the center for the civil rights struggle; or New York, named after the Duke of York once the Dutch had been driven out of their stronghold; or Manchester, New Hampshire, named by Samuel Blodget after one of the much-admired first industrialized cities in the U.K.; or one of the many Londons scattered across the U.S.A.; the names on the maps are unlikely to change even if the majority of the population comes to speak Spanish.

Penny Egan is the executive director of the U.S.-U.K. Fulbright Commission.

The British undertook two contradictory projects in the 17th and 18th centuries: The first was colonization, taking over the lands of the Irish and Native Americans by violence, enslaving Africans and others. The second was a project that they believed set them apart from other European empires: They became ever more committed to a principle of consent in their politics. They beheaded one monarch (Charles I), ousted another (James II), and accepted two more (William and Mary) only with the guarantee that the consent of Parliament, representing the people of the realm, would be essential during their reign.

So when Americans rose to defend representative colonial governments, based on the principle of popular consent, they drew on their British roots. North American colonists never behaved more like Britons than when they declared independence in 1776.

Since then, the U.S. has grappled with this contradictory heritage. The nation adopted coercive policies of empire and rationalized their use, expanding slavery, seizing Native lands, and instituting political inequalities. At the same time, Americans have worked to broaden the arena of consent, extending the vote to new groups, mobilizing to end slavery and secure a greater measure of consent in workplaces and families, as well as government.

Today, the fate of America’s commitment to popular consent remains in play. The sway of big money, disinformation, and voter suppression in domestic politics—and the appeal of adventurism in foreign affairs—reflects the continuing temptations of coercion.

Who will champion the people’s right to meaningful consent? In the past, advocates have come not only from those of British background but from African-Americans, working people, women, and recent immigrants. If history holds, a new demographic might sustain an ideal once considered uniquely British.

Barbara Clark Smith is a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, in Washington, D.C. Her most recent book is The Freedoms We Lost: Consent and Resistance in Revolutionary America.

Each of us carries souvenirs of England’s approach to colonial economics every day. If you have any change in your pocket, odds are pretty good you have a cent, but you almost certainly call it a penny. Since its founding more than two centuries ago, the United States Mint has never struck a “penny,” yet the term for the smallest fraction of the English monetary system has remained ingrained in the American lexicon.

Even though English coins were fairly scarce in colonial America, English denominations—pounds, shillings, and pence—were used in banking and bookkeeping contexts throughout the 13 colonies. An English pound was not the same as an American pound. In fact, Connecticut pounds were not even the same as Virginia pounds. When the cent was first struck in 1792, a “penny” in most Northern states was worth either 1/90 or 1/96 a dollar. Cents have been referred to as pennies ever since.

The dollars in our pocket are also a relic our British heritage. In the eyes of England, keeping the colonies cash-poor was considered good business. Thus, particularly in the late 18th century, English coins tended to be scarce and used almost exclusively to pay debts with England. Silver coins called 8 reales, or “Spanish milled dollars,” filled that void. When Thomas Jefferson and other founding fathers had to create a monetary system from scratch, they defined the American dollar as equal to one Spanish milled dollar. Every dollar we spend today has a history that began in the mines of Mexico, Bolivia, and Peru. And it’s England’s fault.

John Kraljevich is a numismatic historian, author, and dealer, specializing in money and medals of colonial America and the antebellum United States.

The obvious answer is the English language, which has proved remarkably resilient. The question isn’t whether it will remain the most popular first language of the American people—Spanish could overtake English by that measure—but whether English will remain the official language of America, the default tongue of a multi-lingual people. It looks as though it will, for the simple reason that it already occupies that status internationally. If the Chinese, the Indians, and the Brazilians are all conversing in English, it doesn’t make much sense for Americans to insist on talking in a different language.

The English language is well suited to this role because of its capacity to adapt and evolve. Yes, there are a few persnickety grammarians out there, forever complaining about the corruption of the Queen’s English, but there’s no equivalent of the Académie française—an official body whose purpose is to maintain the purity of the French language. On the contrary, speakers of English, including the English, generally welcome the emergence of new offshoots and dialects and the literatures these variations produce. Where would the English novel be without the contributions of John Updike, Saul Bellow, and Philip Roth? Or the postcolonial tradition embodied by Salman Rushdie, Caryl Phillips, and Zadie Smith?

English doesn’t belong to the era of the British Empire; it’s been appropriated and revitalized by its former subjects. To date, student protests about statues and portraits of dead white European males in universities in New Haven, Cape Town, and Oxford haven’t been accompanied by a call for the rejection of our dead white European language. On the contrary, the lingua franca of the Occupy movement, like that of the one per cent, is English. I suspect it will remain the lingua franca of America for at least another century.

Toby Young is a London-based journalist and the author of How to Lose Friends & Alienate People.