Long before I was the English editor of The Rafu Shimpo—the newspaper that covers Japanese-American communities up and down the Pacific Coast and other Japanese-American hubs like Denver, New York, and Chicago—I was a Japanese-American kid from San Pedro seeking out my place in the universe.

In San Pedro, a blue-collar coastal neighborhood defined by the Port of Los Angeles and its large population of Italians and Croatians, I never thought about my cultural identity. Japanese-Americans were once a large presence on Terminal Island, but when the government rounded up the Japanese fishermen and their families in the early hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, most never returned.

In San Pedro, a blue-collar coastal neighborhood defined by the Port of Los Angeles and its large population of Italians and Croatians, I never thought about my cultural identity. Japanese-Americans were once a large presence on Terminal Island, but when the government rounded up the Japanese fishermen and their families in the early hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, most never returned.

So the ties that bound me to the Japanese-American community were modest at best. Even then, I knew how valuable The Rafu Shimpo was. How much it meant.

The first time I appeared in The Rafu, it was during my full ’90s-era glory: giant hair, off-the-shoulder black jersey dress, and a faraway expression.

I had been selected as a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of UCLA and I was acutely aware that The Rafu profiled the new inductees in their annual graduation issue. As incredible as it was to receive the honor from UCLA, I think what meant the most at the time was that I would be featured in the pages of The Rafu Shimpo.

For Japanese-Americans, getting into the The Rafu meant you made it, you were somebody, at least among the vast interconnected community of friends, family, and relations. Friends of your parents who got The Rafu would send clippings. Even for me that community validation was important.

That’s a small slice of what this newspaper has meant to generations of Japanese-Americans. A look at the whole pie reveals that The Rafu Shimpo is the last of its kind: a bilingual Japanese-American daily with two separate news staffs covering politics, civil rights, crime, healthcare, sports.

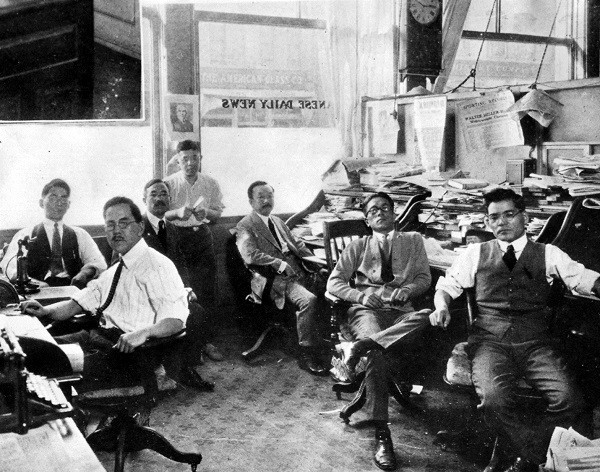

The Rafu Shimpo’s editorial staff in the 1930s

The Japanese edition started first in L.A.’s Little Tokyo in 1903, but its English companion has been running since 1926, when Louise Suski was hired to get it going. The Rafu has spent over a century covering one of the earliest Asian-American communities in the U.S. Six generations now have lived and grown up here, with The Rafu documenting all of it, with the exception of that dark period during World War II when Japanese-Americans were forcibly evacuated from the West Coast and incarcerated in internment camps. Remarkably, The Rafu returned to publication in 1946, less than one year after Japanese-Americans resettled in Little Tokyo. I was conscious of this legacy when I became the English-language editor of the paper in 2002, after working at other Japanese-American outlets and a newspaper in Japan.

When Publisher Michael Komai announced in March that the paper was in a financial crisis and could close in December, I was devastated. And then came the meetings, phone calls, emails, and texts. Many Japanese-Americans and others have come to rely on the paper and cherish it as a link through 113 years of Japanese-American culture and history. They voiced their concerns over the state of the paper and asked how they can ensure The Rafu continues on.

If The Rafu closes, the community itself will develop a sort of collective amnesia.

To give you one example: A white man in his 60s recently came into the office. He had befriended an elderly Japanese-American woman who had recently died and stopped by our office to pick up copies of her obituary. “I just wanted somebody here at the newspaper to know how much what you do meant to her,” he said, explaining that his friend, who was a member of the Nisei generation (American-born children of Japanese immigrants), read the paper everyday from cover to cover.

My aunt called to let me know she had contributed to the subscription effort, and others revealed that their parents worked at the newspaper and even fell in love here. (This is also what happened to me: I met my husband Eric when he worked in the advertising department.)

Rafu was not as central to my parents’ lives. They were among the post-World War II generation that moved their children away from Japanese neighborhoods to, in their case, a predominately white suburb. It was when I visited my Nana Asayo in Gardena, another L.A.-area Japanese-American hub about 30 minutes away from San Pedro, that I was exposed to The Rafu. Nana, who died in 2012 at 104 years old, subscribed almost the entirety of her life. My first attempts to read Japanese were by her side glancing at the newspaper’s front page.

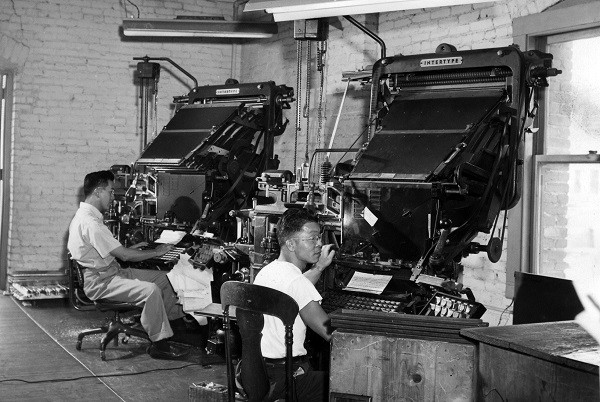

An archival image of The Rafu Shimpo’s typesetters

She was proud of being Nisei, born and raised on the plantations of Hawaii. During World War II she took care of my mom and uncle in a tarpaper barrack at the arid Gila River internment camp in Arizona. The news that she would receive an apology from the U.S. government for this harsh, unjust treatment, came in the pages of The Rafu.

I first joined The Rafu staff in 2000. In the early years, I remember reporting on the fight to keep a jail from being built next to the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple, the quest by Little Tokyo Service Center to find a home for the Budokan gymnasium, and Japanese-Americans finally receiving their college and high school diploma decades after they were uprooted from their schools and homes during the internment period.

Even then, we had crises. The paper was dealing with the rising cost of printing and mailing, plus a lack of vision about how to deal with these issues. Relations between staff and the publisher soured considerably after the abrupt dismissal of the printing staff in the late ’90s. An attempt to restructure the paper and turn around its declining fortunes resulted in the departure of our longtime associate editor and several other reporters. At the end of this process, I was asked to lead the English section in 2002. Since then, I have dealt with the departure of more key staff members, and reductions in the number of days we publish and the physical size of the paper.

In my time as editor, we’ve continued to cover issues the mainstream media hasn’t touched. For example, the sale of the nursing and retirement homes managed by the long-standing nonprofit Keiro Senior Healthcare, which has catered to the needs of aging Japanese and Japanese-Americans for 50 years, to Pacifica Companies, a private for-profit equity firm. Once The Rafu brought this issue forward, readers organized, held rallies, signed petitions, and garnered considerable support from politicians in Washington and Sacramento to prevent the sale. It is hard to imagine this kind of action without a publication like The Rafu Shimpo there to unify and amplify the voices of the community’s diverse factions.

While we’re proud of these moments, we’re struggling with how to preserve the past while embracing the present and future. Our mostly elderly readership is passing away. Their more-Americanized children don’t feel they need to get news from us to navigate their world. Many get their dose of Japanese and Japanese-American culture at blogs like Angry Asian Man and via Twitter. And the community has dispersed out from Little Tokyo and intermarried with groups of other backgrounds. Ask most Yonsei (fourth-generation Japanese-Americans) and their only connection to Japanese America is through basketball leagues.

A typical delivery bag for The Rafu Shimpo, used up through the 1980s

Are historically significant relics of the past like The Rafu still relevant amongst the Yonsei (fourth), Gosei (fifth), and Rokusei (sixth) generations? My answer is yes. First, for those based in Los Angeles, there are too many moneyed power players here in Little Tokyo, whether private developers or government entities such as the Metropolitan Transit Authority, that threaten to alter the neighborhood, one of the last three remaining Japantowns in California. In recent months, a number of historic businesses have closed or been forced to relocate, driven out by higher rents.

Second, even younger generations have an interest in connecting with their Japanese-American heritage. We have been reaching out to young writers and Asian-American Studies professors, who can in turn reach out to their college-aged students. This summer, one of our brightest interns will be spearheading an effort to have student union clubs from all over the Nikkei diaspora (all generations of Japanese immigrants), contribute their work to The Rafu. We are looking into the viability of a Rafu app—to reach our new readers where they read—while we clean up our website and engage with and increase our social media presence.

Our goal right now is to get 10,000 new subscribers (equivalent to raising $500,000 in new income), so the newspaper will survive. These new subscribers would bring The Rafu the capital infusion it needs to update old equipment, pay staff better, and restructure the publication.

Ten thousand is a daunting number. But it’s something many Japanese people won’t flinch at: There’s the Japanese term manpo kei. It involves walking 10,000 steps a day for a long, healthy life.

Send A Letter To the Editors