When I was 17, God put it in my heart to attend Patten Bible College (now Patten University)—and thus brought me into contact with Willa Bebe Patten, a Pentecostal minister who founded the Oakland school.

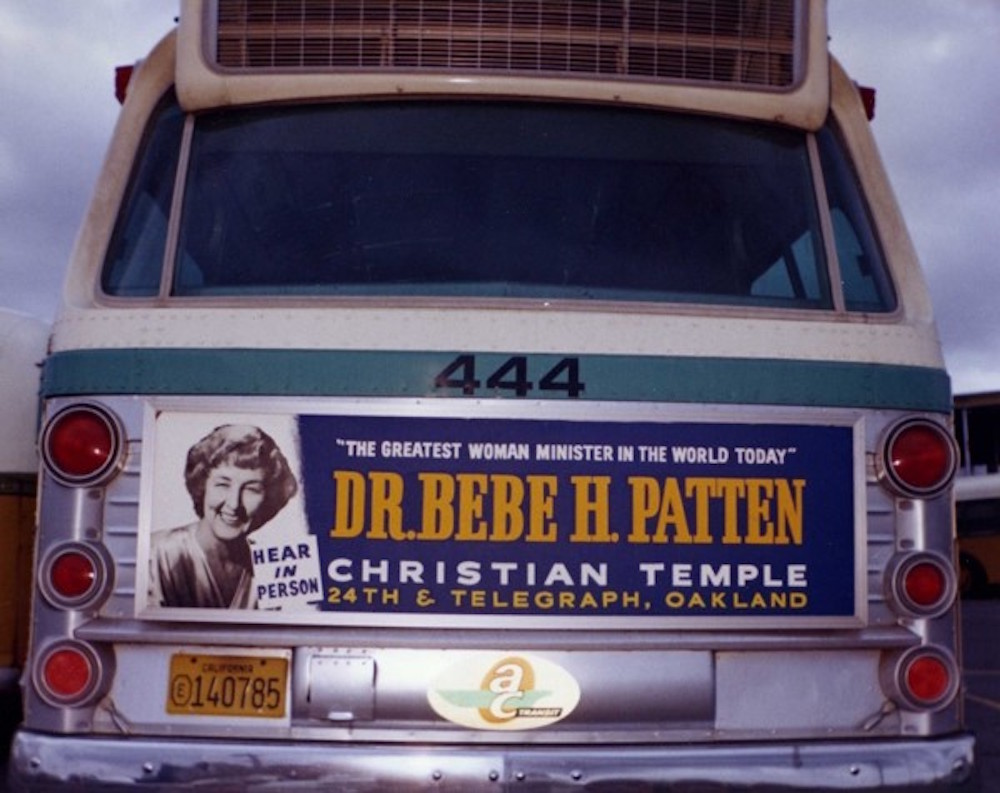

Arriving there, I felt a sense of déjà vu—because I had been born in Oakland and because, as I would later learn, many members of my family rode the bus on Mission Boulevard from Niles (now a district of Fremont) to Oakland to hear the famed woman evangelist Bebe Patten during her early revival services in 1944.

When it comes to Pentecostalism, there is a “there, there” in Oakland. The city has a particular and proud history as a global crossroads for Pentecostals and women ministers like Patten.

Pentecostalism was born in 1906 during a revival on Azusa St. in Los Angeles led by William Seymour, an African-American minister. During this revival Christians embraced the spirit baptism experience, which is evident through speaking in tongues, that is recorded in the Bible in Acts 2: 1-4. Today, Pentecostalism is the fastest-growing Christian movement in the world.

Many Pentecostal denominations have restricted women’s roles in the pulpit and denominational leadership. Nevertheless, many women have determinedly gone into various ministries anyway. They commit their hearts to God and believe that their sole responsibility is to that commitment—not to society, religion, or any church.

The history of women’s ministry is particularly long and rich in Oakland—an unbroken chain, one Pentecostal woman creating opportunity for the next. The tradition extends from Maria Woodworth-Etter—who began her ministry in a test at the corner of 26th and San Pablo in 1889—to Sylvia Vigil, who currently leads many of Victory Outreach’s street ministries.

In between, the story of Pentecostals in Oakland includes many other ministers. Carrie Judd Montgomery founded a faith healing home in Oakland in the 1890s and built her interdenominational and ecumenical ministry here. Lillian Yeomans was part of Montgomery’s ministry in the Laurel District of Oakland. Ernestine Rheems started preaching in a murderous neighborhood in 1968 and went on to build a transitional housing program for homeless single women and found a charter school. Vitely Kiteley, a leader of the Latter Rain movement, began her Oakland ministry in 1965, building a diverse church that became a force in the civil rights and Charismatic renewal movements (in which churchgoers in non-Pentecostal denominations began to experience spirit baptism).

Then there’s Betitia Coty. As a teenager in the 1960s, I was involved in the Chicano movement. The leaders of my church admonished me for my activism; they wanted to focus on saving souls. But “progressive Pentecostals,” like the Nicaraguan-born Coty, embraced activism. Coty ministered to the homeless, women, AIDS patients, and others in Oakland from the 1970s until her death at age 50 in 1996. She is perhaps best remembered for setting up a tent on the lawn of the headquarters of the Oakland Unified School District in 1996 to support teachers during an acrimonious strike—even as she was dying of cancer.

The Oakland story also includes Aimee Semple McPherson, one of the most famous figures of the first half of the 20th century. Though she is better known for her Los Angeles ministry, McPherson received her revelation of the “Foursquare Gospel” while developing a 1922 sermon in Oakland. The city was also the scene of the end of her ministry. In 1944, she flew to Oakland to dedicate a new church. She died there at the age of 53, in the Lemington Hotel, of a probable overdose of sedatives.

Patten is part of this chain. She was a 1933 graduate of LIFE Bible College, an institution McPherson founded. When McPhersen died, Patten was in the midst of a revival series in the Bay Area—soon to become home to her own ministerial and education endeavors.

The first graduating class of Oakland Bible Institute.

By then Patten was an experienced minister, having begun as a “girl evangelist” in Tennessee and having served as a pastor in Cleveland. Her 19-week revival in Oakland was groundbreaking—it gave birth to the Oakland Bible Institute, the Academy of Christian Education, the Oakland Bible Church, and a revival center, all housed in the Alice Theater (currently in the Malonga Casquelourd Center for the Arts on Alice St. near downtown Oakland).

The decades after that brought challenge; her husband was charged and convicted of five counts of grand theft related to mishandling of the ministry’s funds. At that time, his trial was the longest criminal prosecution ever held in Alameda County. Three years into his five-to-50-year sentence, he was released from Soledad prison and he passed away in 1958. The following year, Patten married John Roberto, her co-pastor, but the marriage was short-lived. Like her early mentor, McPherson, Patten would be widowed once and divorced twice.

But Patten’s ministries continued through these difficulties. After the trial, the ministry center moved from the Alice Theater to a converted car garage on Telegraph Ave. In the early 1960s, the church, academy, and college moved again, this time to the Coolidge Ave. campus, where they still reside. In the 1980s, the Oakland Bible Institute became Patten University.

I’m now in my 46th year as a member of the Patten community. Patten was my pastor and my boss. Her gift, especially in working with young people, was making them feel like they—with God’s guidance—could accomplish anything. This went a long way in giving me my own sense of capability in various roles on campus—publication director, high school coach, and finally university professor and administrator.

One of her favorite sayings was, “Bloom where you are planted,” and she definitely gave you the sense that you would indeed flourish in whatever endeavor you undertook.

Women evangelists like Patten were often more innovative and entpreneurial precisely because they were not endorsed by denominations because of their gender. They had to create their own ministry enterprises. Patten’s media efforts included the Trumpet Call, a quarterly publication, the “Shepherd Hour” radio broadcast, and a cable television program.

Patten died on Jan. 25, 2004 at the age of 90. When she passed, she asked that someone from the Church of God succeed her as pastor. Rev. Tobey Montgomery now leads the congregation. In 2012, Patten University experienced extreme financial difficulties and was acquired by UniversityNow Inc. It is now a secular, online university.

The history of Pentecostalism is replete with women who have founded churches, denominations, schools, universities, and social help ministries. Women have also pioneered the presence of denominations in countries, but, because men are sent to formalize that presence, women often do not get the credit for those endeavors.

Pentecostal women like Patten and her predecessors succeeded in eras in which women weren’t thought to have the capabilities to found and lead Christian institutions. Their spirit is visible today around the globe—and across Oakland, where Pentecostal women serve in the classroom and the pulpit, fight human trafficking, and feed the poor.

Send A Letter To the Editors