A High Flying Artist Never Forgot the People Working the Land

Among José Montoya’s Abundant Creative Output Are Thousands of Sketches Documenting Chicano Life

When Richard Montoya started organizing an exhibition of his father’s art, he was astonished at the sheer number of sketches he found. He and his co-curator, Selene Preciado, eventually chose 1,278 out of 5,000. “When did he do all these drawings?” Montoya wondered.

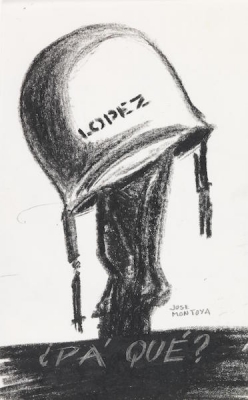

José Montoya led a full life as a writer, a teacher, a musician, an activist, and a fine artist who worked in painting and sculpture as well as drawing. Born in New Mexico in 1932, his family moved in the 1940s to the San Joaquin Valley, where he picked grapes from the age of nine. After high school he joined the U.S. Navy and fought in the Korean War, then used the GI Bill to study art. He taught at a high school and later, after another degree, at California State University, Sacramento, where he became full professor.

Montoya helped to establish art as a crucial part of the Chicano civil rights movement. With several others, he founded an artists’ collective that created posters, flags, and images for the United Farm Workers. They showed up at rallies and picket lines with silk-screening equipment, got a band together to play various events, and painted murals in Sacramento and elsewhere. They also started a breakfast program for low-income students. At CSU he organized student-teachers to travel to remote communities and teach art.

Through it all, José Montoya was helping to raise his six children. He was also writing—he is perhaps best known as a poet, with verse that moves between English and Spanish. He was playing corridos and other music on his guitar (mostly songs he had composed himself). He was painting. And, we know now, he was sketching.

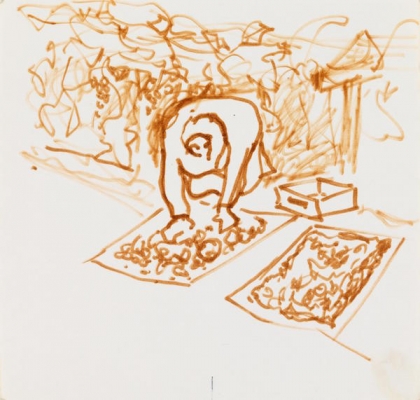

Richard Montoya chalks up this output to an amazing work ethic, “born of his post-Depression-era upbringing [and] pulled into sharp focus” by a heritage of farm labor. Montoya’s high regard for labor grounded his political commitments. In a recent interview, Richard Montoya remembered one family vacation when his father was driving their VW bus from Sacramento to Lake Tahoe and got tears in his eyes. “He said, ‘There’s not one statue to the gold miner or … the Chinese railroad worker … no statues or monuments to the real people that worked the land.’” José Montoya’s art endeavored to provide something like that monument. The exhibition marks his empathy by arranging drawings in boxes that recall grape trays. The show’s title is “José Montoya’s Abundant Harvest.”

Hard work didn’t mean drudgery. Running through José Montoya’s creativity, teaching, and activism was a sense of humor. That artists’ collective, for example, named itself the Royal Chicano Air Force. They dressed in vintage uniforms and joked about “high flying” without ever leaving the ground. Montoya and others once made an adobe airplane, a kind of earth sculpture, to embody this paradox. His art responded to prejudice with style and wit.

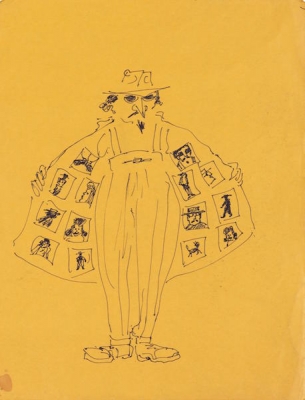

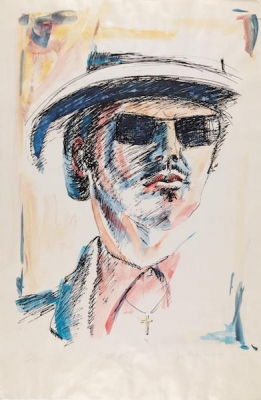

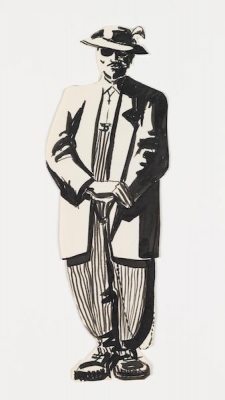

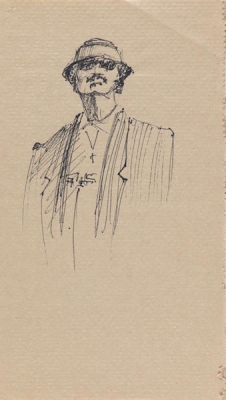

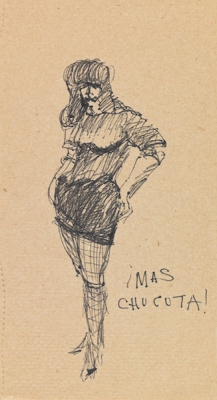

A similar style imbues a figure at the center of the exhibition’s many drawings—the pachuco. Zoot-suited, hatted, impeccably coiffed, pachucos of the 1940s and ’50s were branded as “hoodlums and gangsters” by the mainstream media, Richard Montoya said. The 1943 Zoot Suit Riots were a particularly violent expression of such bigotry. But along with the pachuca, his female counterpart, the pachuco refused—quite fashionably—to render himself invisible in the face of hatred. In Richard Montoya’s telling, the pachuco archetype is part of the moment “when Mexicans became Chicanos.”

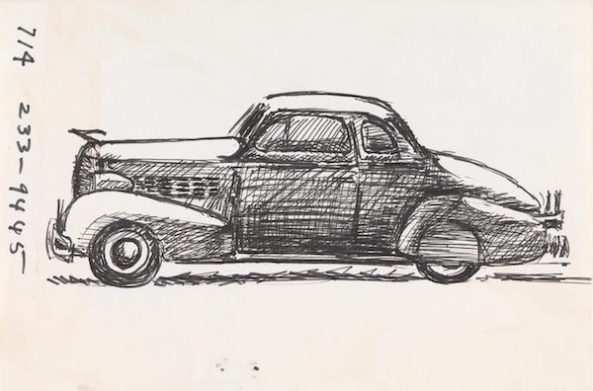

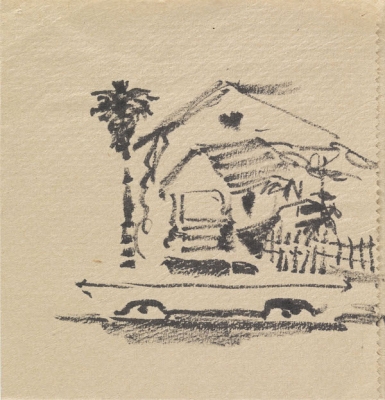

José Montoya lived and recorded that transition. Many of the works in the “Abundant Harvest” are literally scraps—the work of a few minutes, seen from one corner of the cantina, church, union hall, or classroom. Richard Montoya pointed out that his father put down what he saw with economy and respect. “He’s an art man and so his job as an art man is to capture what’s happening all around him.”

Send A Letter To the Editors