Tony Garcci of Richmond, Va., determined to plant a Victory Garden despite the shortages of farmhands and horsepower, works the plow being pulled by his pickup truck, driven by Joe Garcci, April 1, 1943. The job was completed in a few hours’ time. (AP Photo)

Ever since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Americans have faced a set of seemingly unprecedented national security challenges and anxieties. Our society has been consumed with debates about government surveillance programs, overseas counter-terrorism campaigns, border security, and extreme proposals to bar foreign Muslims from America—debates that are all, at bottom, focused on finding the proper balance between keeping people safe versus protecting civil liberties.

Ever since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Americans have faced a set of seemingly unprecedented national security challenges and anxieties. Our society has been consumed with debates about government surveillance programs, overseas counter-terrorism campaigns, border security, and extreme proposals to bar foreign Muslims from America—debates that are all, at bottom, focused on finding the proper balance between keeping people safe versus protecting civil liberties.

This debate is not a new one in American history. Even before the Cold War fears of nuclear warfare, back in the 1930s and 1940s, a similar debate erupted about a different set of security fears and what was then called “home defense.”

During the Roosevelt years, liberal democracies everywhere felt threatened by the rise of the twin absolutist ideologies that were gaining ground across the globe: fascism and communism. News of atrocities committed in the name of these isms—in Ethiopia, China, Spain, the Soviet Union—frightened Americans. Many Americans wanted to join the fight against fascism overseas, while plenty of others embraced isolationism. But all feared the possibility of aerial bombings, chemical and biological weapons, and a panic that could install a dictator in the White House.

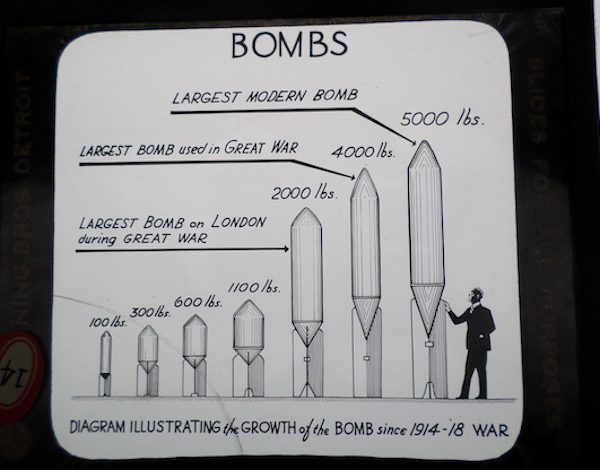

Fear-drenched messages resounded nationwide. Radio dramas such as Archibald MacLeish’s “Air Raid” featured sounds of children screaming as bombs whizzed through the air. Americans read about new “super-bombers” that soon could fly non-stop across the Atlantic and bomb U.S. cities. Theories about how we could be attacked also seeped into the culture: What if the Nazis set up bases in Iceland or Bermuda?

In January 1939, FDR said the world “has grown so small and weapons of attack so swift [that] the distant points from which attacks may be launched are completely different from what they were 20 years ago.” By the spring of 1940, as Hitler’s Wehrmacht rolled across the French countryside, FDR declared that, in essence, isolation was a prescription for national suicide.

“Civilian Defense in Detroit.”

New Deal liberals, previously consumed with trying to expand the safety net to curb capitalism’s sharp edges, began to grapple with citizens’ obligations to democracy in times of crisis: How should civilians work with government to keep themselves and their communities safe from enemy attacks? Should Americans be militarized to prepare for war? Should individual liberties be abridged in the name of protecting America in its hour of need? How should “home defense” help keep civilians calm and maintain their morale? Finally, should home defense improve people’s lives by combatting malnutrition, poverty, joblessness, and despair?

In May 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order establishing the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD)—the precursor to today’s Department of Homeland Security.

There were two competing, bold, drastically distinct liberal visions for what home defense should mean in the lives of Americans. The debate set Eleanor Roosevelt’s social defense vision against New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s brand of national security liberalism. Eleanor Roosevelt was the OCD’s assistant director, the first First Lady to have an official role in an administration; La Guardia was its director while also serving as mayor.

The two of them argued over the classic trade-off between “guns” and “butter.” For La Guardia, the need was to militarize society, whereas Mrs. Roosevelt endorsed “guns” but not at the cost of sacrificing a continued focus on social programs. La Guardia and his supporters were willing to trample on civil liberties, while social defense liberals like the First Lady made more of an effort to defend individual rights and even made a stab at protecting Japanese-Americans from the racist hysteria sweeping the nation after Pearl Harbor.

The First Lady adopted a broad conception of home defense. Her vision featured a government-led and citizen-powered movement to make Americans “as much interested today in seeing [citizens] well-housed, well-clothed, and well-fed, obtaining needed medical care and recreation” as in military security. She insisted that the country had to live its values. In wartime, she argued, “every place in this country must be made a better place in which to live, and therefore more worth defending.”

Eleanor Roosevelt, center, acting as assistant director of civilian defense, at a 1941 conference on “women’s activities in civilian defense.”

To Mrs. Roosevelt, World War II was not only a struggle to defeat fascism militarily. It also required a wartime New Deal to secure a better future by mounting a national effort to attack Americans’ unmet human needs.

The First Lady was charged with overseeing volunteer participation in home defense. She helped recruit more than ten million volunteers, including an estimated three million who performed some type of social defense role. Citizens working through their government fed women and children, provided medical and child care, trained defense plant workers, led salvage campaigns, improved transit systems, planted victory gardens, and helped women learn about nutritious diets. Her campaign helped make it acceptable for liberals to champion big government both in terms of military affairs and social democratic experimentation—a government devoted to both guns and butter.

La Guardia, whose New Deal partnership with FDR had modernized and humanized the nation’s most populous city, embodied the “guns” and anti-civil liberties side of the debate. He worried about social disorder. Watching Rotterdam, Paris, and London being bombed from his perch in City Hall, La Guardia thought that American cities could eventually meet the same fate. Incensed that the administration hadn’t yet established a home defense agency, the mayor lobbied the White House until FDR signed the executive order in May 1941 and tapped La Guardia to be his home defense chief.

La Guardia brandished a new form of national security liberalism that prioritized military over social defense (and individual rights) in times of crisis. Under his vision, a government-civilian partnership would militarize civilians’ lives. He proposed requiring big city workers to volunteer as firefighters and learn how to handle a chemical weapons attack. He recommended distributing gas masks to 50 million civilians, putting a mobile water pump on every city block, and establishing five volunteer fire brigades for every city brigade. A fourth military branch composed of civilians would prepare cities to endure air raids.

La Guardia relied on fear to sell his message. He could come off like Orson Welles (creator of “War of the Worlds”) on steroids. If the public was fearful, he reasoned, it would be inspired to mobilize in its own self-defense.

While he did aid FDR in sowing a war mindset and alerting Americans to the Nazi peril, he also dispensed with civic niceties and civil liberties. In contrast to Eleanor Roosevelt’s reaction to Pearl Harbor, La Guardia asked citizens to spy on other citizens, shuttered Japanese-American clubs and restaurants, called his media critics “Japs” and “friends of Japs,” and ordered Japanese-Americans confined to their homes until the government could determine “their status.”

America’s leading urban reformer pushed liberalism in a novel direction, as he fought to use the federal government to militarize civilians in order to maximize their safety. Ultimately, social defense took a backseat to military security during the Cold War. Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, and John Kennedy launched a range of domestic reforms aimed at strengthening the home front socially and economically, yet military security—loyalty oaths, nuclear arsenals, evacuation drills—typically took priority over social defense. The kind of far-reaching wartime New Deal envisioned by Eleanor Roosevelt was never enacted during the Cold War. Even Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” was cut short partly due to the demand for “guns” during the Vietnam War.

The trade-offs are evident even today. Liberals argue with conservatives and among themselves about the proper balance between individual freedom and national security. Equally controversial, social reforms to improve life at home are locked in conflict with steps to keep us physically safe. This is not just a question of resources. It boils down to how we see ourselves as citizens of our democracy. Some liberals, for example, argue that “nation-building right here at home,” as President Obama suggested in 2012, is as important as cracking down on suspected terrorist threats or planting democracy in the Middle East.

All of these debates are traceable to the struggle among liberals to alert citizens to the war on “two fronts”—at home and abroad—during the Roosevelt years. As long as America has enemies overseas and threats from within, the fight over the best balance between guns and butter and between military security and civil liberties will remain central to America’s national identity—an enduring legacy of the campaign by liberals such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Fiorello La Guardia in World War II to liberate Americans from the grip of fear.

Send A Letter To the Editors