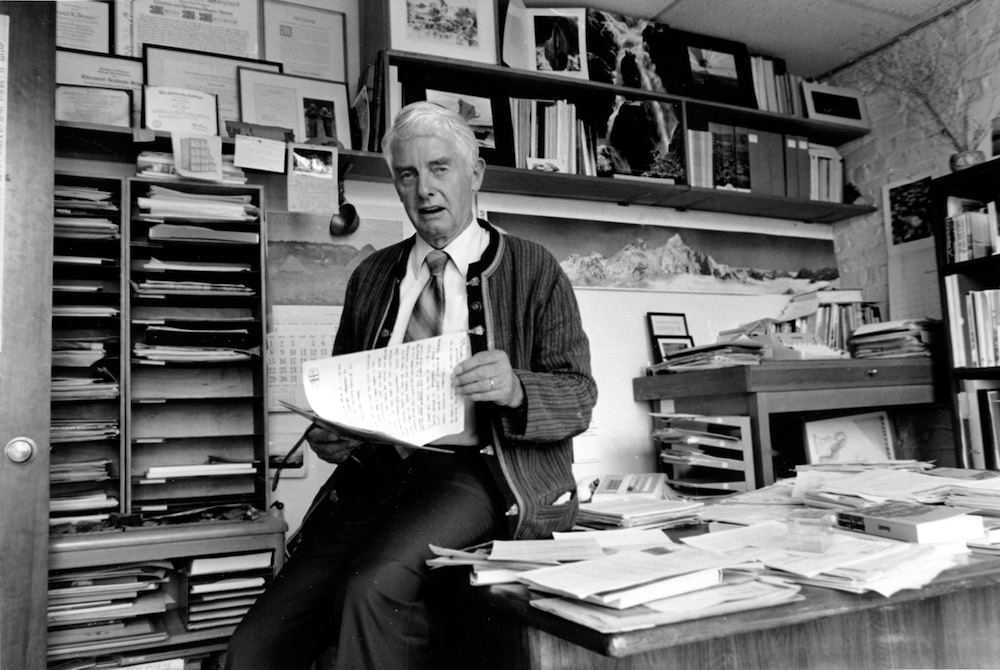

David Brower is shown in his office in San Francisco, Ca., on Aug. 28, 1979. Brower, who was Sierra Club’s first executive director, now heads the Friends of Earth organization. (AP Photo)

Earlier this year, Pacific Gas & Electric Company, which built and operates the Diablo Canyon nuclear reactors on the central California coast, announced that it will phase them out by 2025 and replace their output with renewably generated electricity. When I heard this news I thought of David Brower and the long campaign he waged to close the plant.

Brower, once head of the Sierra Club and founder of Friends of the Earth, is a towering figure in the late 20th century environmental movement—and in my own life. One crucial moment in our relationship came at my parents’ annual holiday party in December 1964. I was 22 and about to graduate from Berkeley and join the Peace Corps for a stint in a Turkish village. We knew the Browers because my mother, Beth, had been friends with David’s wife since the 1930s. I have no recollection of what we were talking about, but Dave interrupted to say, “You have a nice speaking voice. Would you be willing to narrate a film for the Sierra Club?” I gulped and said, “Sure.”

Brower was the first executive director the Sierra Club ever hired, beginning in 1952. He led successful campaigns to block two dams proposed inside Dinosaur National Monument in Utah, helped spark the creation of Point Reyes and Cape Cod National Seashores and Kings Canyon National Park, and launched the Sierra Club into a successful book-publishing program with oversized word-and-photograph volumes celebrating special places the club was working to save. He increased the membership of the Sierra Club nearly ten-fold and was a familiar figure on Capitol Hill, a skilled lobbyist and publicist for nature.

By the time of that holiday party, Dave was approaching the midpoint of his career and was embroiled in a new fight to the death over two proposed hydroelectric dams in the Grand Canyon, a venture spearheaded by President Lyndon Johnson’s administration.

Brower was giving no ground on these dams, especially after he and his conservation allies had acquiesced to the government’s plan to dam Glen Canyon, just upstream from the Grand Canyon on the Colorado River. The move had been a tradeoff to save Dinosaur National Monument, and it was a decision Brower would regret for the rest of his life. Glen was nearly 200 miles long with only the gentlest of rapids, dozens of side canyons of soaring Navajo sandstone, more beautiful than the Dinosaur canyons it was sacrificed to save. The film he asked me to narrate celebrated Glen Canyon, and mourned its loss.

After narrating the film I did my stretch in the Peace Corps, ending in the summer of 1967 with a $5-a-day tour around Europe. From London, I wrote Brower a letter offering my services to the Sierra Club, but claiming no relevant education or experience. Just enthusiasm.

Brower seldom answered his mail. He was, however, known for his long memory, and kept nearly everything on paper for future reference. One of his tenets was that a phone call is nearly always better than a letter, because letters take too long to reach their destinations and get put into piles to be acted on later.

Upon my return from the Peace Corps, I got a job at Head Start. I met a talented young photographer who, when he learned I knew Brower, asked if I’d see if Brower would be willing to look at his work. I phoned, and Dave asked me to drop by his house up the hill in Berkeley later that evening.

The house had been built in 1947 after Brower returned from the war in Italy. River-polished rocks covered most of the horizontal surfaces, and photos and maps adorned the walls. A macaque monkey named Isabelle, rescued from the psychology department at UC Berkeley, roamed the house along with two or three black lab mixes.

Around the dinner table that evening, with plenty of scotch under our belts, Brower asked me to craft a book manuscript from journals and magazine articles written by Norman Clyde, a legendary octogenarian Sierra mountaineer, who also happened to be visiting the Browers. I gulped again, and said, “Yes.”

I went to work for the Sierra Club in May 1968. This turned out to be Brower’s final year at the club, as he had gotten into trouble with his board of directors for various faults, some real, most political. After a vote by the members of the Sierra Club, Dave resigned the following spring and I was fired along with several other partisans.

Dave immediately put the unpleasantness behind him. The rest of us refugees could complain for hours about the injustice we’d just lived through, but Dave had more important things to spend his energy on. He would bravely say that what had just happened was a mitosis, as when a cell doubles itself by dividing in two.

Midway through 1969, Dave, along with a handful of former Sierra Club staffers and volunteers, started Friends of the Earth. It was meant to complement the Sierra Club and other existing organizations, to do the work the club didn’t want Brower to do in its name. This would include a vigorous international program, expansion into campaigns involving energy policy, the protection of public health, pollution abatement, and other concerns beyond forests, parks, and wildlife.

The organization was small and scrappy, and made noise by defeating federal subsidies for a Boeing-built supersonic transport aircraft, delaying construction of the trans-Alaska pipeline for several years (resulting in a far safer pipeline), and leading the crusade against nuclear power, aiming its fire first at the Diablo Canyon reactors on the central California coast.

The Sierra Club board had agreed not to oppose the Diablo proposal in order to save the Nipomo Dunes nearby. A minority on the board thought this a dreadful decision, given Diablo Canyon’s remoteness and beauty. A fierce internal battle erupted within the club. Brower’s opposition to Diablo, in fact, had been one big reason he was chased out of the Sierra Club, the old guard arguing that the club had given its word; others arguing that the club was duty-bound to oppose despoliation of precious stretches of pristine coastline.

At the time, the Sierra Club’s opposition to Diablo was simply because of where it would be built. Later, Brower and many others came to oppose nuclear power altogether because of the plants’ vulnerability to terrorism and natural disasters.

Things went well for a long spell, but in 1986 Friends of the Earth, with finances in bad shape and a deeply divided board, closed up shop in San Francisco, forcing Brower off the board and laying off the staff, leaving only a small operation in Washington, D.C. He must have been discouraged, but again he refused to dwell on the past.

Instead, Dave and several others went to work building Earth Island Institute, which Dave had started a few years prior in case Friends of the Earth decided to dispense with his services. Earth Island is an umbrella that shelters and nurtures dozens of small organizations working on a wide variety of projects in every corner of the world.

I, for my part, took a job with the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund and stayed in touch with Brower, who by then was approaching 80 years of age. We’d meet occasionally for lunch or drinks; he was always full of ideas and suggestions for new projects.

As I neared retirement in 2008 I was casting about for a big project and Brower influenced my life again. Dave had written two ramshackle autobiographical memoirs as well as a borderline manifesto titled Let the Mountains Talk, Let the Rivers Run. However, at the time of his death in November 2000, no one had written a proper biography about him. More distressingly, he was being forgotten. When I talked with young environmental lawyers they only vaguely recalled his name. “I really must do this book,” I thought, “And I hope that it helps keep his story alive.”

Send A Letter To the Editors