What can the city of Rialto, in California’s San Bernardino County, teach the world’s criminal justice agencies? You might think very little given that its police department only serves 100,000 residents and has a front-line force of 54 officers. What you might not know is that the Rialto Police Department led the world in the understanding of how body-worn cameras can change policing.

What can the city of Rialto, in California’s San Bernardino County, teach the world’s criminal justice agencies? You might think very little given that its police department only serves 100,000 residents and has a front-line force of 54 officers. What you might not know is that the Rialto Police Department led the world in the understanding of how body-worn cameras can change policing.

In 2012, we joined with the Rialto Police Department in conducting the world’s first randomised experiment of the effect of body cameras on relations between police and the public. This experiment came about through the foresight of then-police chief Tony Farrar, with whom we—two academics with expertise in criminal justice—co-authored the research. The original project began as a way of cutting red tape, but ended up influencing policing and criminal justice systems around the world, with far-reaching implications.

At the time of the experiment, the Rialto Police Department handled 3,000 property and 500 violent crimes per year, as well as six to seven homicides annually (nearly 50 percent higher than the U.S. national rate per 100,000).

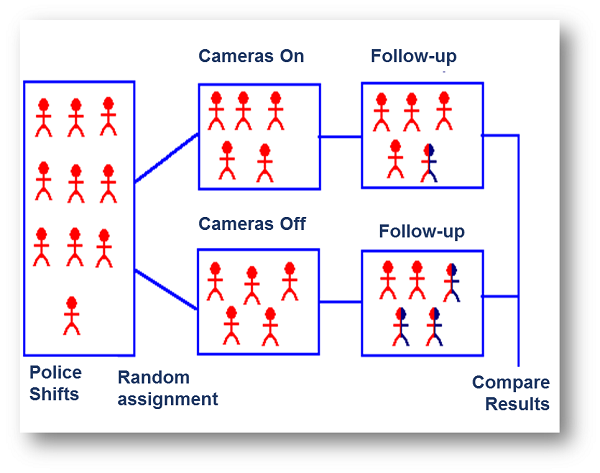

The study randomly assigned whole shifts of officers to wear cameras or not. Each week, all shifts were assigned to treatment (wear cameras) or control (don’t wear cameras). On a treatment shift, all officers had to wear cameras, had to keep the cameras turned on for their whole shift, and had to give verbal warnings to anyone they encountered that they were wearing a camera. The study then compared those shifts where cameras were being used to those where they weren’t (Figure 1).

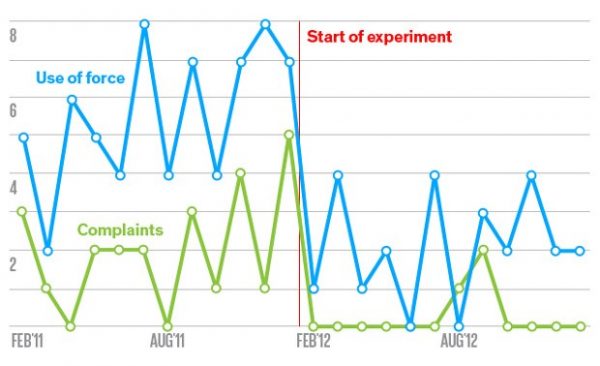

The results were surprising—because they were so clear. When officers were wearing cameras on shifts, police use of force against suspects was 50 percent lower. Similarly, complaints against the police fell to almost zero in the 12 months after the cameras were introduced. Therefore, the cameras caused both use of force and complaints to fall.

Police use of force and the complaints it engenders are expensive for police departments. They cost the trust and cooperation of communities—as we’ve seen with recent tragic and horrific incidents around the country. They’re also financially expensive: A single complaint against a police force can wind up costing upwards of a million dollars in compensation. For a small force like Rialto, that can wipe out the annual budget.

In the wake of the killings by police officers of Eric Garner in New York City and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, President Obama allocated more than $260 million in federal funds to cover as much as half the cost of 50,000 police body cameras, as well as training in their use and community outreach. That amount was also likely matched or surpassed by the amount of money that police forces were already committed to spending on body-worn cameras.

But how do we know that the Rialto results there were not just a one-off? Does success in Rialto predict success in places like Houston and Baton Rouge, where we’ve seen police come under public scrutiny for excessive use of force?

Recently we ran a series of new experiments with 10 police forces across the U.S. and U.K., with more underway. The results from these studies (here and here), generally confirm the Rialto Police Department experiment findings. But there are two crucial caveats: it cannot be left to the officers to determine the shifts during which they will wear the cameras, and the cameras must stay turned on for the entire shift.

As soon as officers are given the powers to decide which cases should be recorded, or at which point during the interaction with the citizen to turn the camera on, body-worn cameras not only can fail, but may backfire. We found that on the one hand, when officers used their discretion to turn cameras on and off during their shifts this was associated with an increased use of force. On the other hand, when officers followed protocol and kept cameras on during shifts, this led to lower use of force.

What we take from this is that when making the decision to invest in body cameras, police departments need to be thinking hard about how they want them used—we think the evidence is good enough to say that cameras should be on before officers are engaged with suspects and (ideally) kept on throughout their whole shift.

And this isn’t just about use of force, but also their role in evidence, police-community interactions and for police accountability. The Rialto Police Department, like many other law enforcement agencies, began using an online system operated by Taser called Evidence.com to streamline tracking of evidence and delivery of cases to the district attorney’s office. This is part of a wider movement of digitization in policing, and Rialto was one of its leaders. Having all the interactions recorded, available for audit if necessary, and electronically coded, added to the overall design of the experiment. We anticipate that this will soon be standard procedure for policing.

If being observed by a body camera leads to greater professionalism, accountability, and a more consensual style of policing, officers may not resort to unnecessary or excessive force. At the same time—and as important—citizens who are videotaped while talking to cops may exercise more self-control and take part in a respectful dialogue with officers of the law, even if they are suspected of breaking the law. The camera keeps both the officer and the citizen in check by reminding them they are being watched.

Body-worn cameras alone cannot solve the problems with policing in America today. But used properly they can help address the mistrust that has grown between some communities and their police.

Send A Letter To the Editors