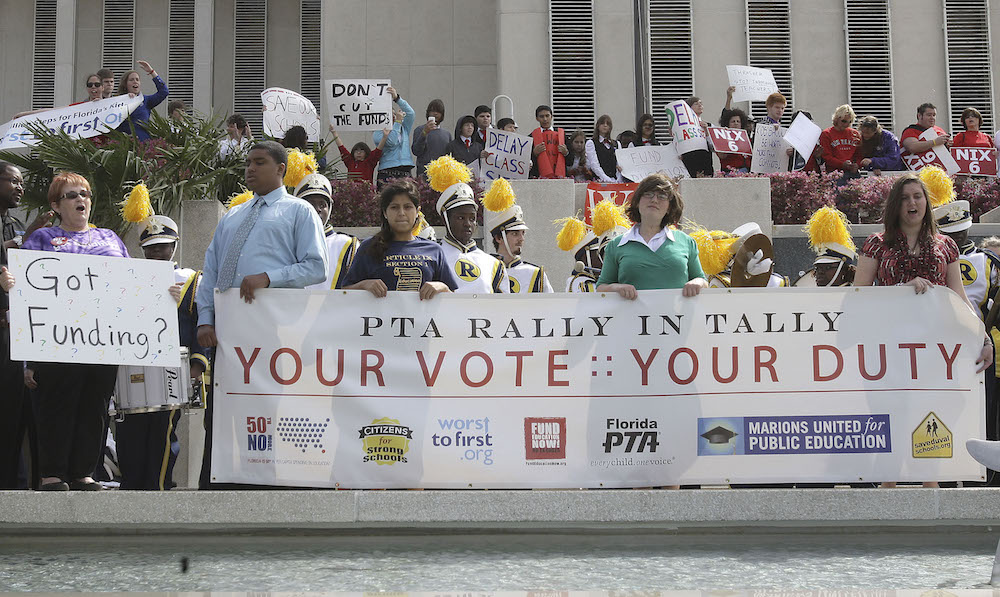

The Parents Teachers Association holds a rally for public education dollars, Thursday, March 25, 2010, in Tallahassee, Fla. At left is former Representative Curtis Richardson who was at the rally in support.(AP Photo/Phil Coale)

Here’s a quick quiz for anyone who has ever had kids or grandkids or nieces and nephews in school: Can you name all of the fundraising items you’ve purchased from the PTA (or whatever acronym represents your committee of ruling parents)?

I can. Over the years, for the sake of my children’s enrichment, I have ordered gold-standard wrapping paper, reusable polyurethane bags, various types of overpriced produce, several mugs embossed with childhood art of questionable quality, and a decidedly non-miraculous miracle sponge.

Most working parents I know have a love-hate relationship with the PTA, that benevolent oligarchy in yoga pants. PTA parents are cliquish and relentless, but hard-working and sincere. And ultimately, they’re not the ones to blame for all of the needling flyers, fundraising packets, and soul-crushing suggestions that if you don’t buy gourmet grapefruit, the field trip to the petting farm won’t happen, and everyone will be sorry.

No, the real problem is a system that has yanked the parent organization from its roots: an advocacy group, founded in the 19th century by women who couldn’t vote, which has successfully pushed for kindergarten, mandatory immunizations, and child labor laws. There’s still a National PTA, based near Washington, D.C. But over the years, many school-based groups have lost faith in its agenda—or decided the dues weren’t worthwhile—and gone independent.

And without a common purpose or an overarching mission, many PTAs have evolved into school-based fundraising machines, largely divorced from the “teacher” part of the name, and generally turned inward. (By the time the country song “Harper Valley PTA” came out in 1968, its clannish reputation had been sealed.)

In the process, PTAs have replaced true community with something that’s essentially the opposite.

Alexis De Tocqueville gushed, long ago, about Americans’ peculiar version of enlightened self-interest, the way selfish motives still somehow led people to lend their time—and property—to the greater good. “The principle of self-interest rightly understood,” he wrote, “produces no great acts of self-sacrifice, but it suggests daily small acts of self-denial.”

Modern parenting culture, though, allows for no denial. For many, the birth of a child is the start of true civic engagement—a stake in the future, a reason to get involved. But that self-interest is channeled to the community that’s exclusively yours.

It starts with the way many American states fund education, with shrinking state aid bolstered by local property tax rolls, so that haves and have-nots are enshrined. Even within smaller towns, school funding is a zero-sum game: Every tax hike becomes a face-off between the needs of kids and the fixed incomes of the elderly, every school board debate a proxy for anxiety about real estate values.

On policy, we’re no better. When it comes to pitched battles over education, where you stand is often a function of what your own child needs. In Massachusetts, a recent ballot question—which would have lifted a legal cap on charter schools—pitted desperate urban parents, eager for good options, against parents who feared erosion of support for public schools. The measure lost, but in the end, nobody won.

And because we don’t fund education as we should, we’re slaves to fundraising drives, easily co-opted by corporate goals. When I was in high school, a local supermarket chain ran a contest: Win an Apple computer for your school by collecting some vast sum in grocery receipts. “Isn’t that unfair to poorer districts?” I asked. My father called me a communist.

This is where the women (yes, it’s still mostly women) of the PTA and independent “PTO” come in—working hard for their kids and no one else’s. It’s not a matter of greed or cold-heartedness, but of structure. In my town outside Boston, the elementary schools in the fanciest neighborhoods hold fundraising galas with silent auctions, and host smoothie bars for the teachers. The ones like mine, filled with dual-working-parent and working-class families, scrape by with bake sales and patched-together carnivals—heartfelt and sweet, but far less lucrative. There is teacher appreciation, for sure, just no smoothies to go with it.

And because so many “extras” deemed important to enrichment are left to the schools to finance, a cottage industry of fundraising schemes has cropped up, purveying products no one really needs. PTAs are deeply susceptible to these ideas.

It all amounts to taxation by guilt, essentially unfair, and inefficient to boot. Once, I spent $25 on a book of coupons to various stores I was unlikely to ever set foot in, on the promise that half of the proceeds—$12!—would go back to the school.

I’ll forever regret that I didn’t put $25 in an unmarked envelope, drop it in the school office, and run in the opposite direction. For the good of the children.

Send A Letter To the Editors