A Uniformed Secret Service officer patrols during blizzard conditions in front of the White House in Washington, D.C., Jan. 2016. Photo by Gerald Herbert/Associated Press.

Donald Trump entered politics as a self-proclaimed “strong leader.” He castigated his supposedly tepid predecessor for lacking necessary strength. Trump, by contrast, would sweep away the establishment and remake America. But Trump quickly faced opposition from, among others, protesters, federal judges, career civil servants, and states. His executive order on immigration, for example, which temporarily banned all travel to the United States from seven majority Muslim countries, is now on hold following an appeal court’s ruling. Even before this, the White House was forced to “clarify” the ban to exempt permanent residents, dual citizens, and Iraqi interpreters for the U.S. military.

All presidents run up against the limited power of the office. To some extent, Trump’s efforts have been stymied by institutional limits on presidential powers and the separation of powers that are built into the American Constitution. The U.S. Presidency was designed to be limited by the courts and Congress.

But the forces that have been holding some of Trump’s changes at bay go well beyond the separation of powers. They reveal something about the nature of power itself and the impotence of self-proclaimed strongmen like Trump when they fail to properly grasp it. Power is not strength. It can never belong to a single individual, nor can it be a feature of a particular office. It is a phenomenon that rises up—and dies—with a group. As soon as the group disperses, power also disappears.

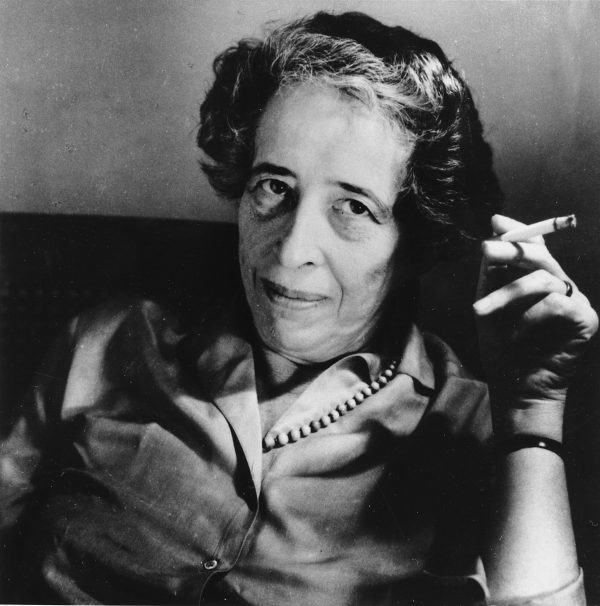

Hannah Arendt, political philosopher and scholar, in 1969. Photo by Associated Press.

The sharp distinction between power and strength comes from the work of Hannah Arendt, the German-American political thinker who was a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. Strength, Arendt explains, is a function of the instruments one can literally possess and hold, whether these are the muscles one has or the instruments one wields. Strength helps an individual act. Power, though, is something entirely different; Arendt defines it as the human ability not just to act, but to act with others. And as such, power can arise only from within a broad, plural, group of people encompassing differences both big and small.

The distinction between strength and power becomes even starker when contrasted with violence. Arendt explores these distinctions in her 1970 essay On Violence, which she wrote against a backdrop of violent student movements around the world and the glorification of violence by thinkers like Franz Fanon and Jean-Paul Sartre. Responding to what she saw as a dangerous conflation of power and violence, Arendt argues that the two are antithetical. Violence, for Arendt, is closely related to strength: It is an instrument that augments strength. But while violence and strength certainly command obedience (it’s difficult, to say the least, to dissent at the barrel of a gun), we shouldn’t confuse either with power, Arendt explains—nor can we conflate obedience with legitimacy. A strongman made even stronger by his possession of the instruments of violence is not, Arendt shows us, more powerful or more authoritative.

American democracy presumes power and resists strength. Resting on the will of the people, our republic was designed to do away with government as the “rule of man over man”—a government that, Arendt notes, the American founding fathers thought “fit for slaves.” Institutions and offices of governance have no power of their own; they are manifestations and materializations of power, which lies only with the people. Thus, if it is to be an office of power and not violence, the Presidency, as much as Congress, needs numbers of people. Without the people, the Presidency loses that “living power” that prevents it from petrification and decay.

But power is not just numbers. The distinction between power and strength is not merely a preference for majority rule. Being powerful isn’t, as political organizers would often have us believe, about speaking with one voice. Power is predicated on plurality. For Arendt, the assemblage of different, if not opposing, opinions and identities is the very thing that gives power to a movement. Arendt describes plurality simply, if a little enigmatically, as “the fact that men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world.” What she means here is that power demands more than the many, or even the majority or everyone, acting together. The group must comprise individuals who meaningfully differ in their opinions from one another such that there are others with whom one acts. It is in acting “in concert” with those who hold different opinions that the power created by a movement remains with the people. If the group can be summed up by one opinion or identity—white working class, conservative, immigrant—the group is no better than an undifferentiated mob that might be swayed to carry out the orders of a dictator. It is no better than a potential instrument of violence.

That potential clarifies the first weeks of the Trump presidency—for both his supporters and his opponents. People have questioned Trump’s legitimacy on a number of grounds: He lost the popular vote, Russia may have interfered in the election, he lacks experience in government. But in some ways the biggest long term threat to his legitimacy lies in his lack of power. By reducing the office to his dictates as a “strong leader,” Trump has signaled that he might see the Presidency more as an instrument of strength than a manifestation of power. His assaults on anyone who questions his decisions, from the press and the judiciary to his own federal bureaucracy, portend a President for whom governance looks suspiciously like the imposition of strength from above that the Founding Fathers sought to eradicate. When Trump revels in the possibility that he might rule solely through the strength of his leadership, he threatens to strip the American political sphere of the various perspectives that make it a constant source of power and legitimacy. He threatens the very power of American democracy.

Through this lens, it is not clear that those who support Trump have much to celebrate, no matter how ardently they may share his views. In acceding to this kind of ruler, we undermine democracy as a system of self-rule and undermine our own power as a people to govern. Indeed, many support Trump precisely because he is “strong” and presumably willing and able to take over the reins of governance from the people. As efficient as strong leaders may be in affecting change, we must be cognizant of what we are giving up in complying with this kind of rule.

At the same time, those who oppose Trump shouldn’t take their own democratic credentials for granted. Power has high standards. Numbers are not enough—not the numbers of the popular vote or the unanimous decision by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (captured by Hillary Clinton’s “3-0” tweet). The burgeoning anti-Trump movement will only become a powerful force in American society when it is a coalition of different opinions that come together for a public good beyond any particular interest. If the opposition can capture plurality, it not only enacts the kind of American society it purports to embrace, but also can serve as a legitimate, democratic force of governance. Its power and legitimacy will come from that fact that such a group can claim to speak and act as a true public—a group of diverse opinions, interests, and identities. Because, as Arendt tells us, what is at stake in politics is not one’s own life and the particular interests one holds, but the world itself.

Send A Letter To the Editors