Writer-philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, who elaborated the concept of existentialism in his 1943 landmark tome Being and Nothingness, shown in his Paris study in 1948. Photo by Associated Press.

Apparently, these are existential times. During the weeks leading up to last year’s presidential election, The New York Times columnist Charles Blow announced that then-candidate Donald Trump was “America’s existential threat.” A Time magazine opiner, doubling down, declared that Trump was an “existential threat” not just to America, but the rest of the world, too.

More modestly, other voices worried that Trump was an “existential threat” to Europe, to the European Union, even to Jordan and Canada. Yet others, less geo-politically inclined, warned that Trump posed an existential threat to conservatives and liberals, journalists and scientists—to cite just a few of the endangered categories.

Even those who earn their keep by parading around in oversize animal costumes have not been spared: Sesame Street fans learned long ago that Trump loomed over Big Bird as an existential menace, because the New York millionaire had called for defunding public television. And after FBI director James Comey was fired—after being deemed yet another existential hazard to American democracy—we were reassured that the memos he wrote of his meetings with Trump posed, yes, an existential threat to our autocratic president. Ride-sharer Uber, without any help from the president, is going through an “existential crisis.”

We have, it appears, entered the age of MEAD: Mutually Existential Assured Destruction.

As a scholar of French political and philosophical thought, with a long interest in existentialism, I’ve spent the last few months trying to straighten out how fear and trembling—the signs that the 19th-century existential thinker Søren Kierkegaard associated with existential crisis—have been grafted onto the widespread response to the Trump presidency.

In the vortex of news and commentary spinning around the Trump White House, “existential” has come to mean the mundane and mere existence of institutions and ideals. It denotes the preservation and continuation of, say, the Republican Party, or the American Republic, of a judiciary independent of the executive branch, or an environment all too dependent on that same executive branch—in short, of life in a world in which Trump has sucked out all of the oxygen.

This kind of existence is not to be sneezed at, but I also worry that the original meaning of “existential crisis,” as it was spelled out by Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus in the middle of the last century, risks becoming yet another casualty of the Age of Trump. By contrast, what we’re calling an existential threat now has solutions, both civic and political. Before the election, Charles Blow suggested that we could resolve it by simply voting for Hillary; since the election, he has argued that the Trump presidency should be “paused” until the relevant authorities sort out the Russian mess.

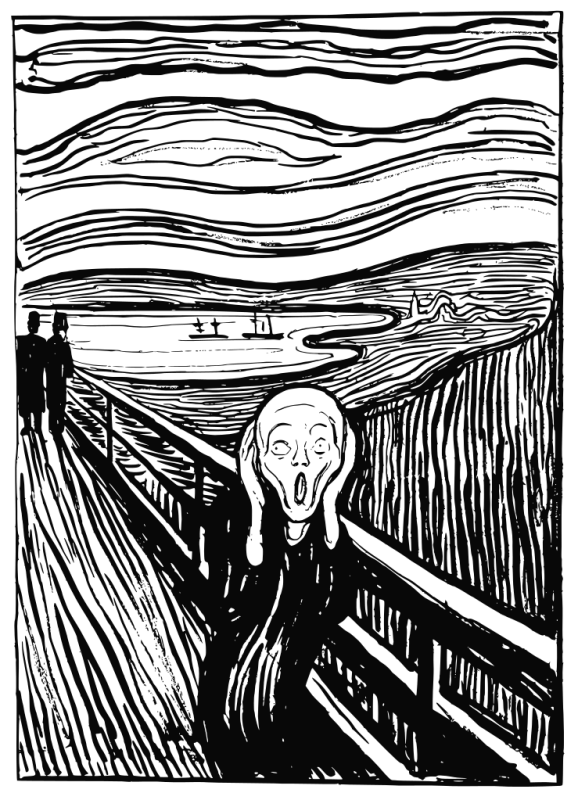

A primal outburst in a void of indifference: The Scream by Edvard Munch. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

No such practical resolutions existed for the earlier brand of existential crisis, and one paused only to adjust one’s black turtleneck, or light up a Gauloise. Simply pushing a button in a voting booth, or signing an online petition, will do nothing for a real existential crisis—for which there is no solution, only more questions. As Woody Allen, the jester of existentialism, once quipped: “I took a test in Existentialism and left all the answers blank. I got a 100.”

To see this distinction more clearly, let’s look at the work of Sartre and Camus—both canny political thinkers who happened to know a thing or two about existential crises.

For Sartre, existentialism has nothing to do with a government we elect to exercise power over the nation. Instead, it has everything to do with the inner government we choose to exercise power over our given situation in life. Sartre maintained that we must assume a radical responsibility for our choices—and our characters—in a world where the traditional measures of morality no longer hold. As he said in his famous 1945 lecture “Existentialism is a Humanism”: We are condemned to be free.

Recognizing this ominous freedom leads to the crisis situation Sartre called “anxiety.” But liberté and angoisse were, like Sartre and his lover and philosophical comrade-in-arms Simone de Beauvoir, a package deal. For a people just emerging from four years of Nazi rule, it is hard to over-exaggerate the excited frisson they experienced when Sartre declared: “We have never been more free than under the Occupation.” Never, he implied, had choices been so charged with meaning, and never had the French been so starkly reminded that choices must be made, and not choosing is the worst choice of all.

Sartre made the choice, in the end, to spend the Occupation comfortably situated with a notebook and pen at a table in the Café Flore rather than joining the Resistance. Whether or not to order a third espresso was about as deep as it got.

While Sartre contented himself with waxing on the absurd, Camus risked his life to take its full measure as well as his own. During the Occupation, he assumed editorship of the clandestine Resistance paper Combat. He had a different understanding of existentialism, a term he always rejected. Existentialism, he said, might serve as a description of our spiritual condition, but it did not offer a prescription for dealing with it.

Camus demanded, as he wrote in The Myth of Sisyphus, a reason to live—something that traditional philosophy had never thought to provide. Such a reason becomes urgent when, as Camus observes, the “stage set collapses.”

A director, actor and playwright, Camus loved the smell and feel of the theater, but his stage set was more than physical. It was the metaphysical foundation we assume exists for the rules and rituals, ideals and ideas, values and virtues by which we live our lives. This metaphysical foundation can collapse, from something as banal as an overheard conversation or as momentous as the German invasion, unraveling assumptions and habits woven over a lifetime. At that moment, he writes, “the world becomes itself again.” Absurdity rises in the space between our demands for meaning and the world’s utter indifference.

Camus never used the precise term “existential crisis,” but he understood that we must live without appeal in a world shorn of transcendental truths and foundational morals. Without warning, a phenomenological two-by-four will one fine day smack us across the head, triggering a crisis that is not practical or political—or not merely one or the other—but instead spiritual.

Once we pick ourselves up off the ground, we will grasp that the practices and rituals, values and truths we had lived by are nothing more than a façade disguising the silence and emptiness of the world. As Camus learned in the Resistance, the necessary response to this absurd condition is rebellion: the struggle to resist the pull of nihilism that churns within this void.

We have, in effect, wrapped the talk of an “existential crisis” around a political crisis, which not only quickens our panic but also numbs our ability to feel the deeper meaning of existentialism. And, ironically, by confusing our terms we are reinforcing, not resisting, Trump’s assault on meaning by confusing the crises we now confront. We have taken the language of Sartre to describe a situation that requires the response of the same Camus who, upon enlisting in the Resistance, declared: “The absurd teaches nothing.”

But embracing existentialism in its fullest form isn’t easy for Americans. The philosophy clearly qualifies as an appellation d’origine contrôlée, grown and bottled on Paris’s Left Bank. Tellingly, French existentialists believed Americans no more could appreciate existentialism than they could savor a slice of Camembert or glass of Sancerre. “In general,” Sartre pronounced, “evil is not an American concept. There is no pessimism in America regarding human nature and social organization.” That Americans took this as a compliment no doubt reinforced Sartre’s despair over our capacity to live authentic lives.

And yet, over the years we have tried mightily to act the role. As George Cotkin recounts in his lively and lucid Existential America, l’existentialisme was all the rage among American students in the 1960s. I recall evenings I spent at the Dial Bookstore in lower Manhattan. Loitering for hours in the philosophy section, I’d scuttle out with a pile of Kierkegaard and Jaspers, Camus and Nietzsche, certain that if they didn’t lead to a suitably grim epiphany, they would at least lead to a conversation with a woman at a nearby bar.

In the end, they led to neither. Still, they did leave a nagging conviction that these writers were on to something deeply, though elusively true and terribly important about the human situation. Walter Kaufmann, who translated Nietzsche’s writings for postwar America, helped me find the words for this sense of things. There are, he wrote, four traits that defined the existential cast of mind: dread, despair, death, and dauntlessness.

I now see we need to pick and choose among these qualities. We still—apologies to Emily Dickinson—cannot stop for Death, while dauntlessness has been outsourced to the likes of Forrest Gump and Kimmy Schmidt. As for dread and despair, we won the lottery on November 8. And I find my interest in misery now has lots of company.

But still, this political dread does not begin to plumb the depths of true existential dread and despair. We rightly feel that the existence of a better future for our children, our republic, and our environment is threatened. Our institutions, our laws, and our ethics are in a state of crisis, and we need to respond accordingly as citizens of this res publica, this “public thing,” which belongs to us all. We are in an acute state of political crisis, which we are unfamiliar with and would like to go away.

But—and here is the rub—the threat of an existential crisis is necessary to live life well. Without the possibility of existential crisis, we might as well be dead: We’d be sentenced to a life poorly or thoughtlessly lived. Whether we’re inclined to sit in the café or run the newspaper for the Resistance, we cannot forget that we need to justify our lives. We are condemned to existential crisis. And that’s a great thing.

Send A Letter To the Editors