Capturing the Architecture of American Agriculture—and a Passing Way of Life

For 45 Years, David Hanks Has Photographed Feed Mills in Every Season and Mood

“Why would anyone want to take pictures of a place like this?”

“Why would anyone want to take pictures of a place like this?”

That’s the question I often get when I enter the office of a feed mill or grain elevator, asking permission to make photographs on the property or inside the buildings.

Showing other photos that I’ve taken usually satisfies the operator that I’m not working for the local tax assessor or real estate agent, and I receive permission to proceed.

But it’s a good question: Why do I keep up with this activity? What is the motivation? There is no coherent explanation except to say that it is something I feel must be done.

For more than 45 years, I’ve been taking pictures of feed mills and grain elevators in the towns of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. Here, the mills—plants that turn grain and other materials into food for farm animals—were once common enough to be taken for granted, even as they often provided a town landmark.

Now, changes in the scale and economics of the agricultural industry have made smaller mills and elevators redundant or inefficient. Some small town mills are still in operation—they might hang on by doing custom grinding (special mixes that depart from the standard recipe to treat particular conditions in animals), or selling lawn and garden products, or mixing for horses and other pets. One I visited even serves ostriches and llamas. But many smaller facilities have been replaced or engulfed by larger ones. Some have been torn down. Some have fallen into disrepair. A portion of history is slipping away.

My documentation of this history began as a passing interest. I worked—I’m now retired—as an industrial photographer, filmmaker, and later, video producer. I have no personal connections to farming or milling. But I like to get outside, and I take pictures of everything that catches my eye. One day in the late 1960s I photographed a beautiful porcelain door knob on a dilapidated building. Later, I saw a similar building while out riding my bike, and I asked someone if she knew what it was. “Oh, that’s the old feed mill,” she told me, and added that it had closed a couple of years before. It was scheduled for demolition. “They’re going to put some stores on the lot.”

A few days later I drove back with camera gear.

I went to the library. I researched. I became a regular reader of Michigan Farmer magazine and the trade journals like the Milling Journal. I learned that 19th-century feed mills were almost always located alongside a railroad track, usually about seven or eight miles apart—about as far as a farmer would want to drive a team of horses on a hot summer day. My collection of pictures grew. I used photos on Google maps to follow train tracks to a likely mill. Often, I’d be directed to my next location by a conversation with a worker at the previous: “Have you photographed the mill in Jamestown? It’s back off the road on 180th Street … Better hurry though, they’re going to get rid of it pretty soon.”

I now have thousands of images of feed mills and grain elevators. I came to know the workers at various places. The owner-operator of a mill in Carson City still remembers when, just a boy, he left a tank of slow-moving molasses unattended, and it overflowed to coat everything—floors, machinery, stored feed. (He had to clean up the mess.) I’ve been told many tales, many as humorous as this one, but also some that bordered on the tragic. These include workers’ anxiety about a passing way of life, their resignation at changes, and their grief over accidents in mills and elevators—which are still more common than they should be.

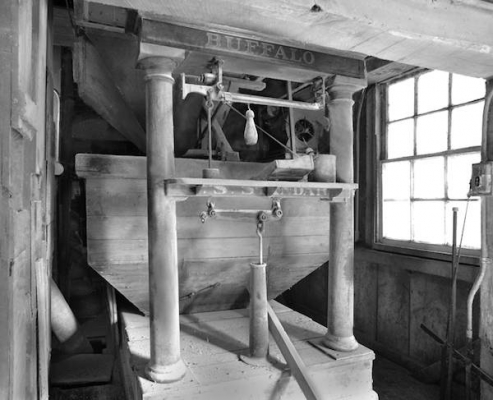

My photographer’s eye remains fascinated by the variety of the structures. They’re true examples of vernacular architecture. As they age and undergo repairs, they often acquire a mix of building materials. One section might include wood shiplap siding, wood clapboard siding, metal siding and a metal roof, corrugated steel, brick, tar paper, and even a car license plate used to patch a hole.

What they don’t include is ornament or decoration. Except for the Christmas Stars. They are made on a framework of metal pipe with lightbulbs attached, mounted at the top of the tallest elevator. The lights are lit eight days before Christmas and are left on until New Year’s Eve. (I have asked a number of times about the reason for the eight days, and the only answer I’ve gotten is “custom.”) When I’m driving on an interstate in December, look out over the snow-covered farm fields, and see one of those stars glowing in the dark, I know that I am in the right place for me.

I’ve photographed mills in every season, even in the rain and snow. I focus most on light. At times, I prefer the low raking angle of a winter sun, which accentuates the deeply engraved textures of an old building. At times, I prefer to photograph when clouds veil the sun to produce a misty cloak over a sharply detailed structure. I capture the pattern of dappled sunlight coming through tree leaves, or I open a door to let bright outdoor light spill across the floor inside.

One of my influences is the French photographer Eugène Atget, who took pictures of Paris and its environs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, concentrating on old and medieval parts of the city. He eked out a precarious living by selling prints to artist supply shops (who resold them to painters as references for quaint old scenes). Atget “viewed the whole world as a finished work of art,” said Berenice Abbott, the American artist who saved his negatives and helped his work achieve recognition, “and photography was just the act of pointing.”

So many old mills have been waiting a long time for me to appreciate them. For my part, I’m only pointing.

Send A Letter To the Editors