Residents of the Russian Far East village of Lorino have returned to their subsistence roots after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. Photo by David Ramseur.

As the Russian city of Provideniya’s deteriorating concrete buildings came into view below, Darlene Pungowiyi Orr felt uneasy. So did the other 81 passengers landing in that isolated far-eastern Soviet outpost in 1988.

They were aboard the first American commercial jet to land there since the United States and USSR had imposed a Cold War “Ice Curtain” across the Bering Sea some 40 years earlier. Orr, a 26-year-old Siberian Yupik Alaska Native, grew up on the tip of Alaska’s St. Lawrence Island, the mountains of Russia’s Chukotka Peninsula visible on the western horizon. Her family’s shortwave radio sometimes picked up chatter in Russian. “That was the language of spies,” recalled Orr, who imagined Soviet frogmen splashing up on her village’s gravel beach.

The Alaska Airlines’ “Friendship Flight” helped melt the Ice Curtain by reuniting Alaska and Russia Native people separated for four decades. As soon as she made her way into Provideniya’s chaotic airport terminal that day, the first person Orr met was a member of her own St. Lawrence Qiwaghmii clan.

That flight and other headline-grabbing initiatives by citizen-diplomats to help end the Cold War launched decades of perilous but prolific progress. These citizen-led initiatives not only overcame a stalemate; they offered a durable model of grassroots international cooperation that could be useful around the world—and even in these familiar Northern climes, where the warming oceans have renewed geopolitical conflict over control of the Arctic.

The history of people-to-people connections here is an old one. After the Bering Land Bridge disappeared under the icy Bering Sea an estimated 18,000 years ago, indigenous peoples from Asia and North America plied the 55 miles between the Alaska and Russia in walrus-skin boats. These Inupiaq and Yupik people spoke common languages and shared similar subsistence cultures, with coastal residents surviving primarily on fish and marine mammals while interior Natives followed vast herds of reindeer, commonly known in Alaska as caribou.

The strait was the site of international cooperation during World War II, as the United States supplied nearly 8,000 Lend-Lease warplanes to assist the Soviet war effort. But soon after the war, Cold War suspicions froze those gestures of good will. The Soviets forcefully exiled Natives living on their own Big Diomede Island, replacing them with a military surveillance post aimed at Alaska.

In 1948, American FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, with the concurrence of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, decided national security interests outweighed those of the region’s Natives. The United States and USSR suspended a 10-year-old agreement permitting visa-free travel by Natives, replacing it with an Ice Curtain which sealed the border and isolated indigenous families on either side.

Darlene Pungowiyi Orr (left) of Alaska meets distant relatives from the Russian Far East village of Sireniki. Photo Courtesy of Darlene Orr.

For the next 40 years, Alaskans and Soviets eyed each other through rifle scopes and the cockpits of fighter jets. At the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, an Alaska-based U-2 spy plane drifted into Soviet airspace and was nearly shot down by Soviet MiG’s. In 1983, the Soviet military blew up a Korean civilian airliner in this same North Pacific neighborhood, killing all 269 on board.

By the 1980s, the last Alaska Natives to interact with long-lost relatives in the Soviet Far East wanted one final opportunity for reunification before passing from the scene. Their quest coincided with Mikhail Gorbachev’s rise to power. Unlike his predecessors, Gorbachev encouraged interactions with the West, burnishing his image as an enlightened reformist.

But Alaska Natives faced intransigence from their own national government. President Ronald Reagan resisted people-to-people overtures as incompatible with his “peace through strength” foreign policy.

So average Alaskans joined the campaign to reunify Bering Strait Natives. Business and civic promoters also jumped at the prospect of contacts with the mysterious Soviet Union after 40 years of isolation.

A Nome realtor engaged in “balloon diplomacy,” attempting to launch weather balloons across the strait carrying goodie bags and messages of friendship. A Juneau musician led 67 Alaska Natives and other performers singing and dancing their way across the USSR to promote peace.

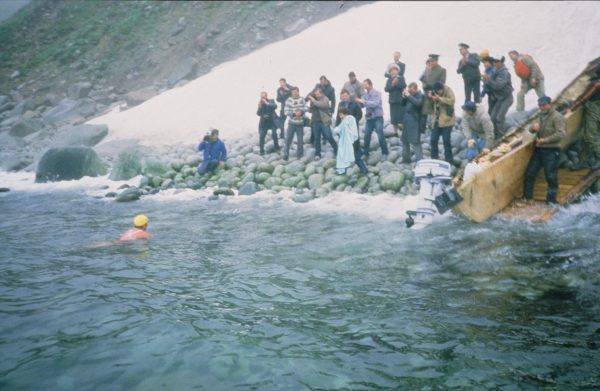

In 1987, a California endurance athlete swam the 2.5 miles between Alaska’s Little Diomede Island and Russian Big Diomede in 38-degree seas in nothing but a swimsuit, goggles, and cap to highlight Cold War tensions. A medical doctor born to glitterati Hollywood parents returned to his Alaska Native roots to dedicate his career to reuniting Bering Sea Natives by addressing their common health challenges.

These efforts finally won the blessing of both national governments and launched decades of chaotic but often productive interactions in business, culture, science, and education, with thousands of Alaskans and Russians crossing the International Date Line on regular flights by Alaska Airlines and other air carriers. Nearly 60,000 Russians learned western business practices in training centers set up by Alaskans across the Russian Far East. Enticed by Alaska’s guarantee of in-state tuition, more Russian students attended the University of Alaska Anchorage than any other American university.

Alaskans helped form dozens of Russian Rotary Clubs that improved care to elderly pensioners hit hard by the Soviet Union’s 1991 collapse. Alaska and Russia communities rushed to establish sister cities to strengthen civic and commercial ties. And scores of Alaskans and Russians married, settling in each other’s countries and advancing cultural understanding.

Endurance swimmer Lynne Cox approaches a snowy beach on Soviet Big Diomede Island after becoming the first person to swim across the Bering Strait from Alaska’s Little Diomede Island in 1987. Photo by Claire Richardson.

With the dawn of the 21st century, relations cooled across the strait as well as between Moscow and Washington. Russia’s rip-the-bandage-off transition to a market economy under Boris Yeltsin was too chaotic for many U.S. companies. Vladimir Putin’s subsequent rise to power was initially welcomed for stabilizing the economy, but as his regime restricted the operations of international companies and non-profits and infringed on human rights, many westerners ceased their involvement with the country.

Today in the Bering Strait air service is limited and visits are burdened by bureaucracy and high costs, so contacts are rare. Relations between countries at the highest levels also have deteriorated as tit-for-tat sanctions, expulsion of diplomats, and crackdowns on “foreign agents” harken back to the Cold War.

The year 2017 was the 150th anniversary of America’s purchase of Alaska from Russia. At many events marking the occasion, Alaskans said they remained inspired by the vision of William Seward, President Lincoln’s Secretary of State, who consummated the Alaska purchase. Seward, a bold internationalist, believed Alaska could advance a U.S.-Russian relationship and strengthen America’s standing in the world.

Fulfilling Seward’s vision of U.S.-Russia cooperation could start with the natural affinity between citizens of the Far North regardless of national borders. Alaskans and nearby Russians are challenged by common problems—climate, geography, transportation, indifference from our national capitals—for which common solutions can work.

That’s especially the case among the indigenous peoples who struggle on both sides of the strait to preserve traditional languages and culture, combat substance abuse, and scratch out a subsistence way of life endangered by climate change. A 1989 U.S.-Soviet “visa-free” agreement for travel by Alaska and Russia Natives remains in place, but contacts suffer from costly and irregular transportation.

Managing a rapidly changing Arctic is the area of greatest potential cooperation between our countries. Nearly half the world’s Arctic falls within Russia, and the United States is an Arctic nation only because of Alaska. As Russia beefs up its fleet of some 40 ice-breaking vessels and opens scores of mothballed Soviet-era Arctic military bases, the United States and Russia should expand joint efforts for search and rescue, environmentally sound resource development, and scientific research.

Three decades ago, Alaskan and Russian citizen-diplomats melted the formidable Cold War Ice Curtain separating them in the face of significant resistance. Many were branded kooks, communists or worse. Juneau musician Dixie Belcher was summoned to the Alaska legislature to explain her suspected ties to the KGB, while Alaska Gov. Steve Cowper was criticized for cozying up to “reds.”

Darlene Orr was so inspired by that day-long visit to Provideniya that she mastered the Russian language and returned to the Russian Far East 13 times, dedicating her career to researching Native languages and native plants. On one trip, she ignored warnings about visiting restricted areas, dressed herself as an average Russian, and spent a long day on the coast harvesting seaweed and mushrooms.

“It was worth any risk to me to visit the shoreline where my ancestors had walked,” she said.

Inspired with courage and persistence like Darlene Orr, Alaska and Russia citizen-diplomats overcame enormous obstacles to transform history.

Send A Letter To the Editors