Battling for the ball during a pickup game in Senegal. Photo courtesy of Sebastian Abbot.

Over a decade ago, I was running on a treadmill at a hotel gym in downtown Cairo, where I was working as a journalist for The Associated Press. The place was small and gloomy, but given Cairo’s terrible traffic and pollution, it was one of my only workout options. The gym’s saving grace was that it had TVs that allowed me to watch European soccer matches while I ran.

On this particular day in 2007, a commercial showed a young boy playing soccer at a glittering sports academy called Aspire in the tiny ultra-rich desert kingdom of Qatar. I’ve been a soccer fan my entire life. I started running around the pitch as a five-year-old and had the pleasure of playing at Princeton under future U.S. national team coach Bob Bradley. So when I got home from the gym, I Googled “Aspire Academy” to learn more.

I was surprised to discover that Aspire, a state-owned sports academy built at a reported cost of over $1 billion, had launched the largest talent search in soccer history earlier that year. They were, in effect, looking for unicorns: those rare young players who can excel at elite international soccer. I would eventually join the search and learn much about both the sport and the nature of talent itself.

The program, called Football Dreams, was bankrolled by one of Qatar’s richest men, Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad Al Thani, a member of the country’s royal family. It was led by Josep Colomer, a former youth director at FC Barcelona who helped launch the glorious career of Argentina’s Lionel Messi.

In 2007, Colomer and his fellow scouts held tryouts for more than 400,000 13-year-old boys in seven African countries as they looked for soccer’s next superstars. Out of this pool, they chose the best two dozen players and flew them to Doha where they were scheduled to participate in a weeks-long final tryout at Aspire. The plan was to select a handful of the best kids and train them to become professionals at the biggest clubs in Europe. Aspire presented Football Dreams as a humanitarian program, but many people suspected the true goal was to lure these boys into playing for Qatar’s national team since the country lacked the population to produce world-class players on its own.

A boy takes a shot at Ibrahima Dramé’s soccer school in Ziguinchor. Photo courtesy of Sebastian Abbot.

Soccer has long been called the global game, but the program took globalization to an almost absurd new extreme. Where else could you find a Spanish scout working for a Qatari sheikh hunting for African players to send to European clubs and possibly one day the World Cup?

I flew to Doha in January 2008 to spend a few days with the African boys while they were at Aspire for their final tryout. I tried to make sense of what I found and wrote an article about the program for the AP.

Years then passed as I moved to Islamabad to cover Pakistan and other parts of the world. I embedded with U.S. troops battling the Taliban in Afghanistan and spent time with Libyan rebels waging war against Qaddafi. But Football Dreams stayed with me. I always wondered what had happened to those talented African boys I spent a few days with in Doha. I was intrigued by whether Qatar would find soccer’s next superstars and what the country’s motivations really were.

In 2014, I decided to leave my job at the AP to write a book about Football Dreams. The program had become even more fascinating over the years as it expanded outside Africa and held tryouts for millions of boys. Qatar also bought a club in Belgium to serve as a farm team for these players as they sought to complete the journey from the academy to the world’s top clubs.

My research turned into a four-year odyssey that took me to 10 countries across four continents. I spent months in West Africa visiting the towns and villages where the boys came from; stood on the sidelines of the same dirt fields where they played growing up and were spotted by Qatar’s scouts; and even hitched a ride with a Nigerian militant to visit a small fishing town where Colomer hoped to find the next Messi.

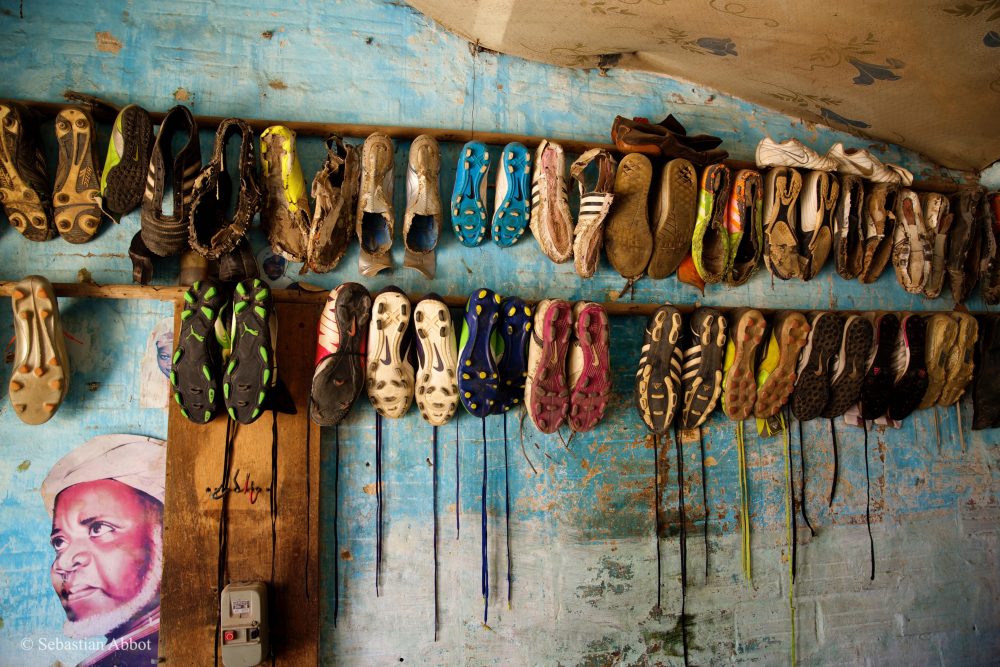

The inside of a shop that specializes in repairing soccer cleats in Kaolack, Senegal. Photo courtesy of Sebastian Abbot.

In Qatar, I raced across sand dunes in a 4×4 with new Football Dreams recruits while they were in Doha for their own final tryout. In Belgium, I bellied up to bars in the small town of Eupen to hear what locals thought about the fact that their team, the Pandas, was now owned by an Arab country they knew little about and filled with African teenagers.

Along the way, I realized that while the program represented the extreme edge of soccer’s globalization, it was indicative of how much more international the sport has become in recent years. This is especially true at the youth level. When Messi first showed up at Barcelona in 2000, it was extremely unusual for the club to contemplate taking a 13-year-old boy from Argentina into its famed academy. A few years earlier, accepting a kid that age who lived near the club would have provoked debate. But as the hunt for global soccer talent has accelerated, teams have started focusing on younger and younger players all over the world.

One of the other big takeaways was just how difficult it is to identify which kid has the potential to become a star—even for experienced scouts like Colomer, who know what to look for. They understand that physical traits like size, speed, and strength will tell them relatively little about a player’s potential. Even technique has its limits. The most important factors are mental ones, like game intelligence and personality, but these are the hardest to measure. As a result, the success rate of picking kids who make it to the sport’s top level is incredibly low, even at the best academies. Only one-half percent of the kids who join a Premier League academy in England at the Under-9 level end up making it through the years to the club’s senior team. That’s one in 200 players

A player traps the ball during a pickup game on the beach in Senegal’s capital of Dakar. Photo courtesy of Sebastian Abbot.

That hasn’t stopped clubs from aggressively recruiting kids as young as five years old. Much like venture capital investing, the money made from one spectacular success, or saved by not having to buy an equivalent player, can make up for a high number of failures. But kids aren’t companies, and there’s a serious personal cost for the thousands who don’t make it. Plenty of players who are identified as the next big star at a young age dedicate thousands of hours to training and then watch their career prospects peter out over the years. Along the way, players are forced to sacrifice time with family and often end up neglecting their schoolwork. Many struggle to find a new path when a professional career doesn’t work out. Of course, there can be real benefits to academy life as well: camaraderie with teammates, learning the importance of hard work, and so on. But the sting of failure can be painful and lasting.

Unfortunately, that proved true for many of the Football Dreams players. They all believed they were destined to become stars in Europe. After all, they had been marked for greatness in a process that was more than a thousand times more selective than getting into Harvard. They also had a rich Arab sheikh in their corner. But even then, only a fraction succeeded in living out their dream and making it to major European clubs. The game is just that hard. Many of the others ended up playing at low levels in Europe, returning to Africa, or washing out of soccer altogether. Those who watched their dreams fade away often complained that Aspire didn’t do enough to help them find a new way forward.

This is the harsh reality of international soccer. It’s littered with broken dreams. Even so, the supply line of young dreamers will continue, especially from many places in Africa where making it to Europe can seem like the only way up and the only way out. It may be a nearly impossible dream, but for many of them, the away game seems like the only game worth playing. They don’t focus on the 99 percent chance of failure. They see the one percent chance of success.

Send A Letter To the Editors