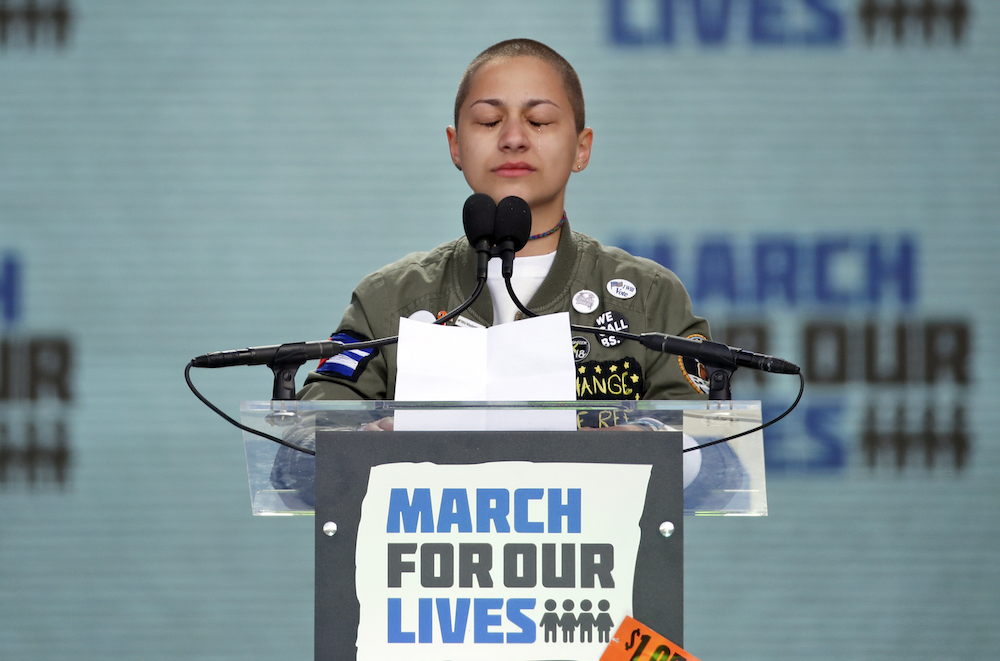

Emma Gonzalez, a survivor of the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., closes her eyes and cries as she stands silently at the podium for the amount of time it took the Parkland shooter to go on his killing spree during the “March for Our Lives” rally in support of gun control in Washington, Saturday, March 24, 2018. Photo courtesy of Alex Brandon/Associated Press.

Since the 1960s, so-called “youth movements” worldwide have been led by college-aged students. What has been less accepted, and less noted, is that children under 18 also have participated in social movements throughout history. Often they have been written out of the history of these social movements or given only a mere descriptive mention.

One example is Barbara Johns, who in 1951 at age 16 led a student strike at Moton High School in Prince Edward County, Virginia, to protest overcrowding and inadequate conditions at the segregated school there. Johns said that she knew that the students needed to act independently first before calling for adult allies. After two weeks of striking, the students enlisted support from the national NAACP, becoming one of the five cases that made up Brown vs Board of Education in 1954, which legally overturned school segregation. The significance of Barbara Johns’ activism has taken many years to be recognized. In 2008, a memorial sculpture of Barbara Johns leading fellow student strikers was included with three others statues at the Virginia Civil Rights Memorial. In 2012, a documentary film was released, Barbara Johns: The Making of an Icon.

Still, such examples remain little known. And so the emergence of young students as activists after the shooting deaths of 17 at Parkland, Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School has surprised and confused some adults. There have even been those who have claimed these students are “coached” and could not possibly come up with these ideas and demands themselves. Some schools are weighing what age might be too young for a student to protest and how school administrators should respond to school walkouts. As 16-year-old Parkland survivor Alfonso Calderon said at a rally following a meeting with Florida lawmakers, “Although we are just kids we understand. We know. We will not be silenced. I don’t feel we should ever be silenced just because we are children …. ”

Why are children’s protests forgotten or treated as illegitimate? The problem lies not in the kids themselves, or their protests, but in the way the rest of us see children in Western society. Today, in the United States and much of Europe, children are seen as inhabiting a protected sphere, educated and cared for within a family and school setting, free of social responsibilities and the world of work. In such a protected space, the idea of children needing rights, let alone demanding them, seems incongruous and unnecessary.

The very idea that childhood is a protected space is a recent one, historically. In his classic 1960 book Centuries of Childhood, historian Philippe Ariès analyzed medieval depictions of childhood in art and literature, to show that children of that time period were treated as “little adults,” without a separate culture of social life and play. That began to change in the 18th century, with French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ideas that children were innately innocent and closely connected to nature. The Romantic period built on this myth of innocence by imagining “childhood as state of paradise” as represented in literature by poets like Wordsworth. Based on this idealized conception of childhood, the 19th and 20th centuries became increasingly child-centered, with institutions catering to the education and entertainment of children.

Detail of Virginia Civil Rights Memorial, in Richmond. Photo courtesy of Sylvester S./Flickr.

Politically, children in the modern world have often been treated as non-rational actors in society, if they are considered actors at all. Various rationale have been put forth to defend this image of a dependent and non-political childhood, one of which is that children lack the cognitive abilities to understand complex social and political issues. In 1990, sociologist Jens Qvortrup published “Childhood as a Social Phenomenon: A Series of National Reports,” which detailed the status of children in 16 industrialized nations, concluding that economic, social, legal, and political structures in adult society, rather than simply ideas about children’s developmental stage, contribute to making children into a politically powerless class.

In other words, the design of modern citizenship makes children exist only as pre-citizens, for whom the scope of legitimate political engagement and expression may be very limited. Thus, worldwide, 16 is generally the youngest age for voting available, with 18 the more frequent age limit of voting rights.

The most extensive document establishing the rights of youth is the Convention on the Rights of the Child which was adopted in 1989, by the United Nations General Assembly; but its history and perspective on what those rights are is telling. The current document originated from the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child adopted in 1924 by the League of Nations. Though not legally binding, this early document was a call for basic human dignity and welfare for children globally, as a response by early child reformers to the social conditions of European children after WWI.

The idea of rights for children was expanded in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child in 1959, when the concern was expressed that, “the child, by reason of physical and mental immaturity, needs special safeguards and care, including appropriate legal protection …. ” This phrase remains a guiding principle of the current children’s rights document.

The current Convention on the Rights of the Child states that children and youth should be afforded certain protections and also elaborates further on their rights, including that of voicing their own views and the freedom to peaceably assemble and express these views with others. All 196 member-countries of the United Nations—with the very notable exception of the United States of America—have signed and ratified this document.

Despite these concerted efforts, in reality, children and youth do not live in a separate protected paradise and instead are exposed to serious social problems—war, slavery, abuse, homelessness, labor exploitation, poverty, and racism—in societies around the world. Adults have taken up these causes to “save” children and attempt to provide them with human rights. And yet, because of the continued belief that children are living with a protected status, children’s own protests about these conditions often have been overlooked.

This concept of the protected status of children puts children at a distinct political disadvantage. Because children are politically marginalized, adults who oppose their message can disregard their protests. On the other hand, adults who might be otherwise sympathetic to the children’s cause may get caught up in the symbolic nature of the ideal of the protected childhood. And the dissonance between that ideal and the reality may cause them to not take children seriously as politically conscious actors.

Nonetheless, like adults, children become socialized into activism from actual events in their lives. This process—the experience, the empathy, the reaction to unjust situations, and then mobilization—follows a similar path to that of youth and adults who become engaged in a cause. Sometimes mobilization over injustice brings children and adults together. In 2008 in Greece, the shooting of 15-year-old Alexandros Grigoropoulos by police led to riots by children, youth, and adults. The rallying cry for the ongoing organized protests was, “It Could Have Been Us,” a statement summarizing the young protesters’ reflection on their feelings of a lack of safety and protection as children. The event proved to be a political awakening for some younger participants, who subsequently protested against austerity measures in 2011.

Throughout history children have been involved in social movements as strategic participants, as participants by default, and in very active roles. This last type of participation seems especially difficult to grasp. Since Ariès’ work was published, social scientists have tried to grapple with how children can be understood as active agents in their own lives. A new multidisciplinary field of Children’s Studies, or Childhood Studies emerged in the 1970s, becoming fully established in the United States and Europe in academic programs and research centers that conduct research on the larger social and historical context of children’s everyday lives.

It’s clear that the idea of a protected, innocent childhood is a myth that we can no longer continue to hide behind when the reality of children’s lives are so much more complicated. Precisely because children are not protected in society, they not only have the awareness and the motivation to protest, they also have the right. And despite the discomfort it may engender for some adults, child protesters will be a continuing phenomenon in society as long as they are subject to injustice.

Send A Letter To the Editors