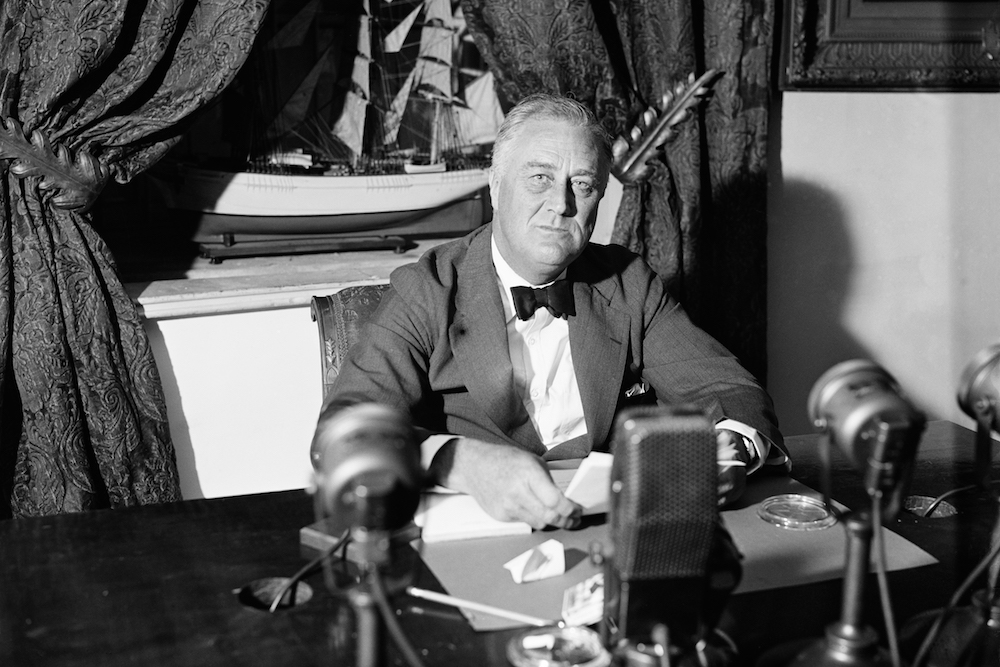

President Franklin D. Roosevelt making a national address at the White House, Sept. 6, 1936. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

At $20 trillion, the national debt of the United States is slightly bigger than the annual output of the American economy. Government shutdowns and brinksmanship about extending the country’s debt ceiling have greatly raised the risk of default. So what would happen if the U.S. actually went off the fiscal cliff, and was unable to pay its debts? To answer that question, we have one historical data point: the great debt default of 1933-1935, when Franklin D. Roosevelt, Congress, and the Supreme Court agreed to wipe out more than 40 percent of America’s public and private debts. What were the consequences of that default for America and the world? And what does this history tell us about the risks of an American default today? UCLA Anderson School of Management international economist Sebastian Edwards, author of American Default: The Untold Story of FDR, the Supreme Court, and the Battle Over Gold, visits Zócalo to explore the threat of American financial peril. Below is an excerpt from his book.

This is the story of a forgotten episode in U.S. history, the story of the great debt default of 1933–1935, of the time when the White House, Congress, and the Supreme Court agreed to wipe out more than 40 percent of public and private debts.

There are many ways of telling this story. But possibly, the best starting point is April 5, 1933, when President Roosevelt, who had been in office for exactly one month, issued an Executive Order requiring people and businesses to sell, within three weeks, all their gold holdings to the government at the official price of $20.67 per ounce. The Order was published in every newspaper and transmitted over thousands of radio stations. Large signs were placed in post offices around the country. The posters were printed in large block letters and informed the public that everyone had “to deliver on or before May 1, 1933, all gold coin, gold bullion and gold certificates now owned by them to a Federal Reserve Bank, branch or agency.”

Those who didn’t comply with the Executive Order faced “criminal penalties . . . [a] $10,000 fine or ten years of imprisonment, or both.”

The public was shocked. Throughout the history of the nation, gold had been used as a store of value, and many families owned gold coins as part of their savings. Gold was given as wedding presents and at bar mitzvahs, and newborns often received a gift of one or two coins from their godparents. The fact that all metal had to be turned in to a relatively new institution—the Federal Reserve had been created less than twenty years earlier—made things even worse.

As the May 1 deadline approached, radio announcers reminded families of what they had to do. People could still not believe what was happening. It was true that during the previous months there had been an extraordinarily high demand for the metal and that hoarding had increased sharply, but that was exactly how the system was supposed to work: from time immemorial people resorted to gold when they faced economic uncertainty, including fears of banks’ collapses.

[The default process had begun in] the early hours of March 6, when he had been barely one day in office, [and] President Roosevelt declared a national banking holiday. Its purpose was to stop massive withdrawals of currency and gold, and to put in place an emergency plan to strengthen the nation’s financial system. A week later, on March 13, banks began to reopen their doors, and people redeposited their cash and gold in massive amounts.

So, if things were improving, why was the government forcing the public to part with their gold? Coercing people to sell their hard-earned metal was not an American thing to do. This had never happened before, not even during the Civil War, when the gold standard was suspended and the Treasury issued “greenbacks.”

The weeks that followed changed America forever. Between March and June, 1933, Congress passed legislation that would fundamentally alter the way the economy functioned, and set the basis for the welfare state. Some of this legislation was later challenged in the courts system, and some was eventually declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. There is little doubt, however, that these feverish weeks of continuous debate and lawmaking planted the seeds of a new America, a country where the federal government would take an active role in economic and social affairs, a nation that would create an intricate safety net for the poor, the unemployed, and the disadvantaged.

While the foundations of the American economy were being profoundly changed by one act of Congress after another, the gold saga initiated with the April 5 Executive Order continued to unfold. On April 19, during the thirteenth press conference of his young presidency, President Roosevelt stated unequivocally that the country was now off the gold standard. He explained that the fundamental goal of abandoning the monetary system that had prevailed since Independence was to help the agricultural sector, which had been struggling for over a decade. He declared: “The whole problem before us is to raise commodity prices.”

The next step in this drama came on May 12 when Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA). Title III of this legislation included the “Thomas Amendment,” which authorized the president to increase the official price of gold to up to $41.34 an ounce. A devaluation of the dollar, many thought, would rapidly result in “controlled inflation” and would help farmers by raising commodity prices and by lightening their debts when expressed in relation to their incomes. A number of experts noted that Great Britain had devalued the pound in September 1931, and had slowly begun to recover.

Things, however, were not as easy as they seemed. In the United States, most debt contracts—both private and public—included a “gold clause,” stating that the debtor committed himself to paying back in “gold coin.”

These clauses were introduced into contracts during the Civil War, a time when two currencies circulated side by side—a currency backed by bullion and one unbacked, the so-called greenbacks issued by the Union’s Treasury. Debts that included the gold clause were considered to be more secure, since the amount to be received in payment at some future date was anchored to the price of gold and, thus, not affected by possible changes in the purchasing power of paper money. After the end of the Civil War there had been no need to invoke them, but with time gold clauses came to be considered a “normal” component of debt contracts; it became customary to include them in corporate and utilities bonds, and in many mortgage contracts. In 1933, however, it became evident that these clauses were a problem. If the currency was devalued with respect to gold, the dollar value of debts subject to the clauses would automatically increase by the amount of the devaluation. This would result in massive bankruptcies and in a huge increase in the public debt. For all practical purposes, then, when FDR was inaugurated as president the “gold clauses” stood in the way of a devaluation of the dollar.

Three months after Roosevelt had become president, on June 5, Congress passed Joint Resolution No. 10, annulling all gold clauses from future and past contracts. This opened the door for a possible devaluation. Republicans were dismayed and argued that the nation’s reputation was at risk. The government, on the other hand, claimed that the Joint Resolution didn’t imply “a repudiation of contracts.” The secretary of the treasury stated that since gold payments had been suspended in April, all Congress had done was clarify that “the holder of an obligation can- not specify in what type of currency [gold or paper money] the contract is payable.”

On January 31, 1934, the other shoe dropped when President Roosevelt officially devalued the dollar by fixing the new price of gold at $35 an ounce, an increase of 69 percent relative to its century-old price of $20.67 an ounce. Conservatives deplored the decision, and argued that it would inevitably lead to a steep decline in America’s power. Others, including the farm lobby, were disappointed by what they considered an insufficient adjustment in the value of the dollar. In explaining the decision, FDR said that the devaluation was necessary, since the nation had been “adversely affected by virtue of the depreciation in the value of currencies to other Governments in relation to the present standard of value.” Many considered this to be a direct reference to the devaluation of Sterling.

Not surprisingly, those who had purchased securities protected by the gold clause claimed that the Joint Resolution of June 1933 was unconstitutional. Various lawsuits made their way through the courts system. Four of them got to the Supreme Court, and were heard between January 8 and January 10, 1935. Two had to do with private debts, and two with public obligations. The most salient case involved a government bond in the series of the Fourth Liberty Loan issued on October 15, 1918. The obligation for this “4¼ % Gold Bond” expressly stipulated that “the principal and interest hereof are payable in United States gold coin of the present standard of value” (Perry v. United States). The question before the Court was whether Congress had the constitutional power to alter contracts retroactively. Could Congress annul private and public debt promises and, in the process, affect the wealth of debtors and creditors?

On February 18, 1935, the Supreme Court announced its decision. In all cases the Court voted 5 to 4 in favor of the government position. The majority’s opinions were written by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, a distinguished jurist who had been governor of New York, secretary of state, and presidential candidate for the Republican Party in 1916.

There was a single dissent signed by the four conservative members of the Court, known as the “Four Horsemen.” When the time came to deliver the minority opinion, Justice James Clark McReynolds, a southern lawyer who favored bow ties and had served as attorney general during Woodrow Wilson’s first administration, decided to depart from protocol: instead of reading the prepared text he gave a short speech. He opened his remarks in a low tone. Slowly, he raised his voice and his southern tones quivered with anger. A minute into the speech he paused; it was a classical pregnant silence. He then said: “The Constitution as many of us understood it, the instrument that has meant so much to us, is gone.” He then talked about the sanctity of contracts, government obligations, and repudiation under the guise of law. It was clear, he stated, that Congress had the power “to adopt a monetary system. But because Congress may adopt a system, it doesn’t follow that this may be enforced in violation of existing contracts.” He ended his speech with strong words: “Shame and humiliation are upon us now. Moral and financial chaos may be confidently expected.”

Send A Letter To the Editors