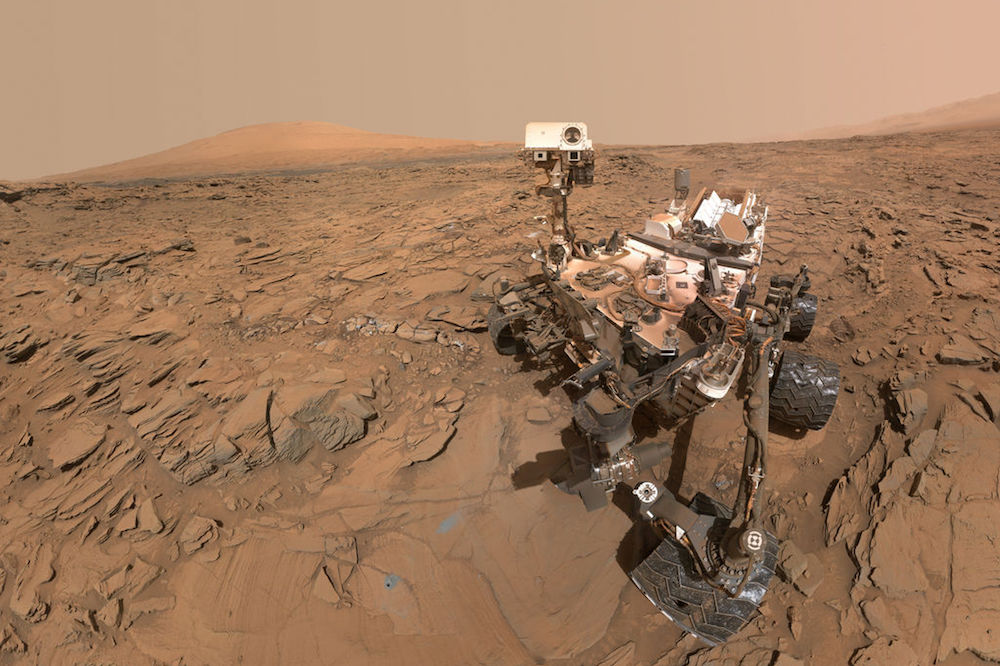

Selfie image taken by Mars Curiosity rover, which is wandering the surface and (among other activities) sniffing the atmosphere for traces of methane. Photo courtesy of NASA.

Humanity has dreamed of going to Mars for decades. Mars appeals to us as a possible second home because of how Earthlike it is—and how much more Earthlike it might become, given a whole lot of human ingenuity and planet-scale engineering. Furthermore, Mars has the potential to be habitable by humans, though it is potentially already inhabited by microorganisms that could be DNA-based life forms.

Recently, NASA, SpaceX, Blue Origin, the Mars One Foundation and the Mars 2117 Project all have their eyes on transporting humans to the red planet. The future seems to be coming at us quickly, but the questions of whether we should go to Mars, and what we need to know before we make that decision, are big ones that don’t get nearly enough attention.

Our obsession with Mars-travel started in the 19th century. In the 1890s, astronomer Percival Lowell barnstormed the United States, telling audiences that intelligent Martians had built canals on Mars. In the same decade, H. G. Wells stoked the public’s fear with his Martian invaders in The War of the Worlds. A short time later, our infatuation with going to Mars began. In 1910, The Edison Production Company released the five-minute film A Trip to Mars, and two years later Edgar Rice Burroughs published his first John Carter on Mars stories as Under the Moons of Mars. Shortly after the dawn of the space age, NASA flew Mariner 4 past Mars in 1965. Only six years later, NASA put Mariner 9 in orbit around Mars, not long after Neil Armstrong took the first human footsteps on another world. Suddenly, Mars beckoned to us in a more realistic way.

Part of the appeal of Mars is that Mars is Earthlike in many ways. It rotates in just over 24 hours, so a day on Mars is almost identical to a day on Earth. Like Earth, Mars has seasons and polar caps, though each Martian season is almost twice as long as a season on Earth. Mars has a solid surface, a thin atmosphere, and sunrises and sunsets. Martian day would follow Martian sunrise. Martian spring would follow Martian winter. The rhythm of life on Mars would share the same pulsations and rhythms of life as back home on Earth. We could adjust to Mars. We very possibly could live on Mars. At the very least, we can imagine ourselves living on Mars.

Actually living on Mars would be challenging. All terrestrial life requires water and, fortunately, we now know that Mars has enormous amounts of water, albeit frozen at the polar caps, locked in permafrost or buried in aquifers deep underground. With effort, we probably could retrieve and then pipe that water to our Martian cities. Thus, the presence of great volumes of water, as much as any other attribute, makes Mars potentially habitable.

Because Mars is farther from the Sun than Earth, it receives fewer warming rays of light, and so the temperature on the surface is below freezing most of the time on most of the planet—but not everywhere all the time. The average cold temperature on Mars (minus 80 F) is just a bit below the average temperature at Earth’s south pole in southern winter (minus 57 F) and is hundreds of degrees warmer than the deep, lethal cold of Pluto (minus 400 F). Temperatures on the Martian surface have even been measured to be as warm as 68 F. Initially, we could take blankets, solar panels and nuclear power generators with us and find ways to stay warm. Then we could develop ways to warm up the atmosphere. We could, eventually, get comfortable on Mars.

Even if we managed to make these things work, we would have a more significant problem: oxygenating the atmosphere so that we could breathe. Mars currently has no free oxygen, but it has plenty of carbon dioxide that plants can use for photosynthesis and from which human engineers might extract breathable oxygen. Given enough time and ingenuity, one can imagine that we could find ways to solve this no-air-to-breathe problem. For the foreseeable future, Mars is at best a sanctuary for anaerobic life forms that can thrive at extremely cold temperatures.

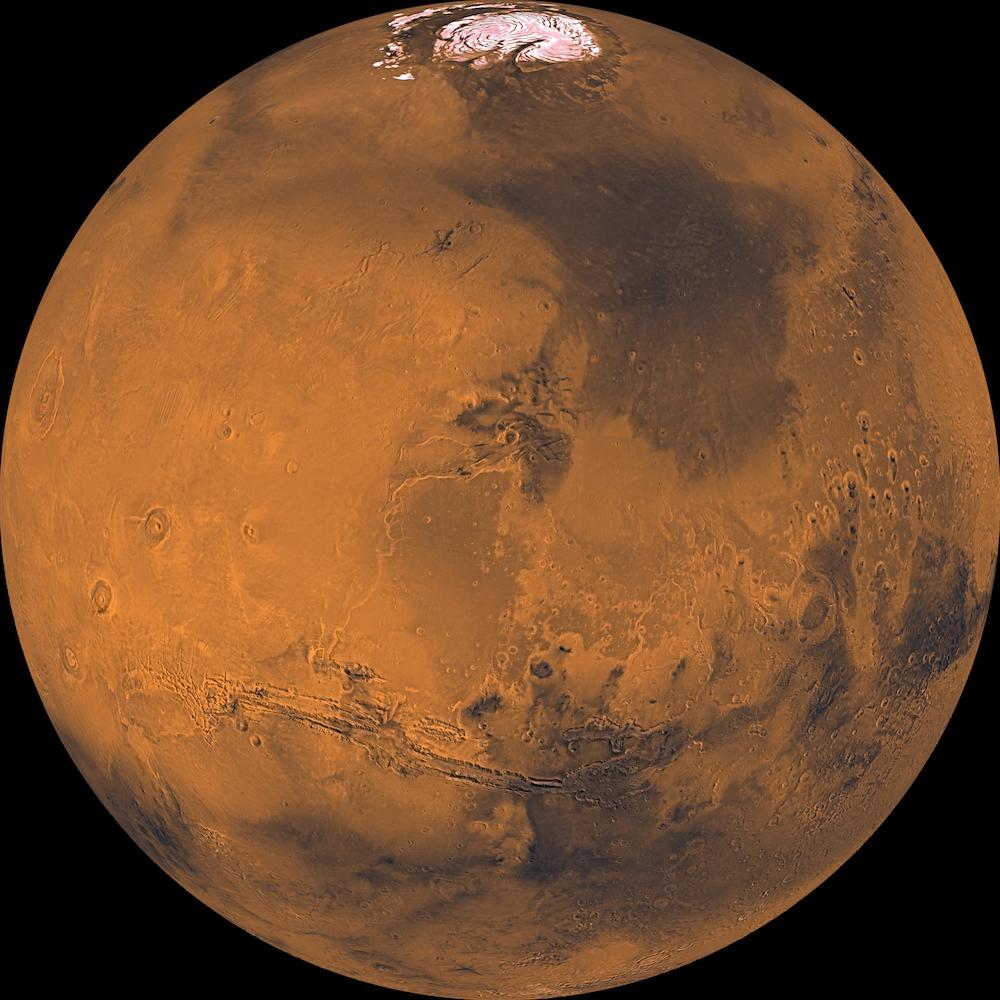

Photo courtesy of NASA.

Even if we did solve all of these problems, living on a planet that lacks an ozone layer to protect life on the surface from dangerous solar ultraviolet light and X-rays would be no fun. Furthermore, the thin atmosphere of Mars offers no protection from the high-speed particles known as cosmic rays that come from the Sun and other stars in the Milky Way. Without the protection of a thick atmosphere and an ozone layer, the surface of Mars would be a terrific place to spend time if your goal is to develop radiation poisoning and cancer and then die.

Of course, scientists are working on solutions to these problems, too. We could start by living in caves or bunkers below the Martian surface. Or maybe we’ll figure out how to manufacture shelters made of special protective materials. Then, over a long period of time, we might engineer the Martian atmosphere to become more like that of Earth, a process known as terraforming.

Despite the potential of Mars to be a second home for humanity, or even our only home if we destroy the one we currently occupy, we’re just not ready to go to Mars yet.

Our most obvious problem is that, right now, a trip to Mars would be a one-way journey. SpaceX might be able to launch some potential colonists to Mars within a decade, and NASA soon thereafter, but with current rocket technology, neither SpaceX nor NASA can bring these spacefarers home. Whether potential Martian pioneers can survive, let alone prosper, on Mars is an open question, but the technology for a round-trip ticket to Mars simply does not exist yet, and the ethics of sending astronauts on a one-way journey to Mars are questionable.

Establishing a colony in a new, unknown world carries great risks. Those of us who send emissaries to another planet should make every effort to minimize those risks.

Chief among those potential risks is one aspect of colonizing Mars that has been ignored: Mars may already be inhabited. As Carl Sagan noted when peering at Mars through the eyes of the Viking landers’ cameras in 1976, Mars has no macrobes—no bears, no rabbits, no mice, no wasps. Mars could, however, be host to an underground world of microbes. Some scientists have interpreted their measurements of small levels of methane in the Martian atmosphere as evidence that Mars already is inhabited. This interpretation is controversial and by no means definitive, but it also may be right. The best we can say, today, is that we do not yet know for sure that Martians exist; however, we also do not know for sure that Mars is sterile. The jury is still out.

Before we begin to contaminate the red planet with our DNA, bacteria, and viruses, we need to establish whether Mars is biologically alive or dead. Pre-existing Martian life likely would have no defenses for the contamination we would insert into their world. And if Martian life exists and is related to terrestrial life through DNA or RNA molecules, we might have no defenses against the unintentional but inevitable contamination of Earth with Martian microbes.

That such elemental questions about the presence or absence of life itself on Mars have not yet been solved suggests that we do not know enough to consider living on Mars at this time.

Can we justify the risks to the lives of potential space travelers, when so many known problems related to surviving a trip to Mars remain unsolved? SpaceX’s plans to send the first crewed flights to Mars in 2024 may be premature. And if Mars is already the home of Martians, they have squatter’s rights. Perhaps we should leave them alone.

Send A Letter To the Editors