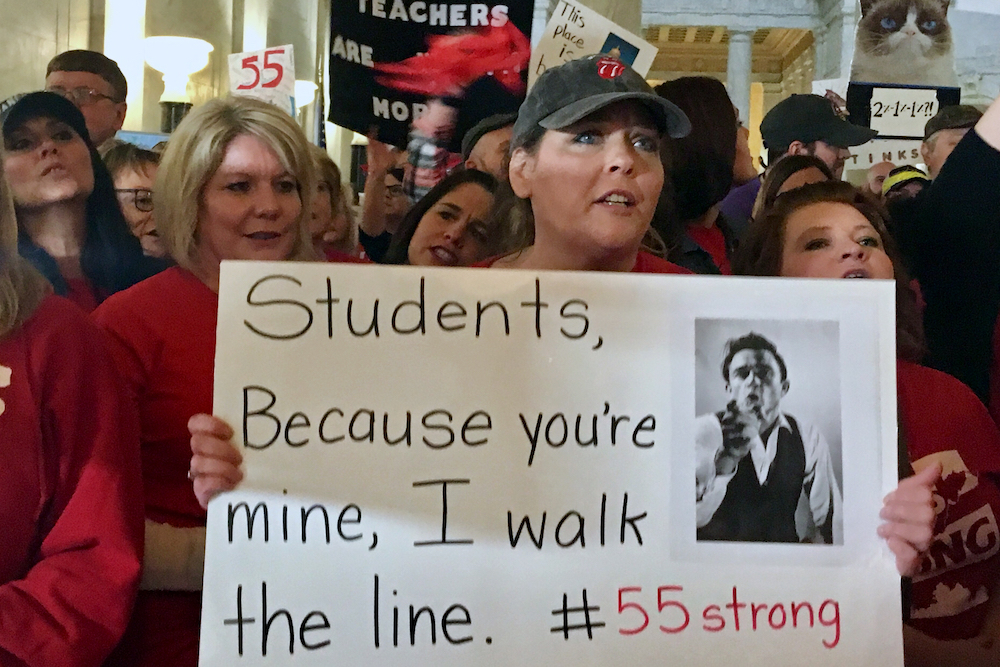

Jennifer Hanner, a first-year teacher from Harts, West Virginia, holds a sign outside the state Senate chambers in Charleston, as teachers went on strike over pay and benefits in February, 2018. Photo by John Raby/Associated Press.

In states across the nation, public school teachers are going out on strike. What does that tell us about the future of labor in America?

On February 22, 2018, some 20,000 West Virginia public school teachers and staff walked off their jobs, closing schools in all 55 counties in the state. Thousands of teachers, school employees, and supporters flooded the state capitol in Charleston, protesting low salaries and rising health insurance costs.

Scattered walkouts had begun in January, especially in the rural southern coalfield counties, some of the state’s poorest areas. The strike proved to be a formidable weapon that helped dramatize the issues at stake. “The strike made people aware of how bad things were,” said Jay O’Neal, a middle school teacher in Charleston. “When people found out, they were sympathetic.”

The tactic worked. After nine days out, the state agreed to a 5 percent pay increase for teachers and other school employees, the creation of a health insurance task force including representatives from the unions, and a temporary freeze on rate hikes. Within weeks, the West Virginia strike was followed by mass walkouts of public school teachers in Arizona, Kentucky, and Oklahoma, protesting low pay and budget cuts to public education. Collectively, the teachers’ actions formed one of the largest upsurges of labor militancy in the United States in decades.

These dramatic events call for some analysis, because they stand in sharp contrast to the long-term historical pattern: a deep decline in strikes. During the 1970s, an average of 289 major work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers occurred annually in the United States. By the 1990s, that number had fallen to about 35 per year, and in 2017 there were no more than seven.

The steep falloff cannot be explained simply by the decline of unions. According to one report, union membership declined by around 12 percent between 1990 and 2015, from around 16.7 million to 14.8 million workers (split roughly evenly between 7.6 million members in the private sector and 7.2 million in the public sector). During the same period, however, the number of strikes fell by around 87 percent, or at a rate approximately six times faster.

What has happened to the strike, and what does it mean for workers and for American society?

The general decline in strikes has occurred alongside processes of economic globalization and technological change that have transformed the world of work. Neither of those forces by themselves, however, requires the elimination of either unions or strikes—as is shown by the example of other industrialized nations such as Canada and many European countries. But in the United States there has been a profound change in the legal and institutional order governing labor relations and workers’ rights, including the right to strike.

The recent upsurge of militancy among school teachers stands out against this background. To start, one should note that the wave of teachers’ strikes has occurred in the public sector, where, unlike in the private sector, labor relations are governed by state laws that can vary significantly. Several states, mainly in the South, do not permit collective bargaining by public employees, while many others limit the types of public workers eligible and the scope of their rights, and most do not allow strikes. Yet it is precisely in those states with limited labor rights where the current wave of teachers’ strikes has emerged.

The key to this paradox lies in the historic origins of the broader institutional framework for regulating union-management relations in the private sector. Before the 1930s, American unions confronted a legal environment that labor historians have described as “judicial repression.” During that time, federal courts repeatedly struck down workers’ rights to organize and act collectively, making unions themselves all but illegal. As the economy became increasingly dominated by large corporate employers, individual workers were left with little say over the terms and conditions of their work.

The labor movement fought back in bitter and often bloody struggles, but formal collective bargaining procedures were as yet poorly established. Strikes seemed to challenge public order and the balance of power among groups, and all too often employers and the government responded with armed guards, police, or troops. In the landmark struggles of the era—of the steelworkers in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1892; the nationwide Pullman railroad strike of 1894; and the coal miners’ strike in Ludlow, Colorado, in 1914—the use of force resulted in tragic losses of life.

That dynamic shifted with the passage of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA, also known as the Wagner Act). In a pivotal breakthrough, the law finally addressed the fundamental power imbalance in the labor market between large employers and unorganized, individual workers. Congress recognized that the effect of the imbalance was a burden on the economy, depressing wage rates and the purchasing power of workers and leading to conflict and unrest in the workplace. To overcome these problems and encourage the mutual settlement of labor disputes, the law created a framework for legally certifying union representation and for governing the terms and conditions of employment through collective bargaining.

The result was an historic democratization of the American workplace and economy. A crucial part of this system was protecting workers’ right to strike. Unlike the tripartite arrangements more common in Europe, in the United States the federal government did not intervene directly in contract negotiations. Rather, the law relied on workers’ ability to strike to guarantee the integrity of the bargaining process. The prospect of economic losses from either strikes or lockouts served to push both sides to compromise and negotiate a peaceful agreement. Thus, the right to strike was explicitly protected in the language of the NLRA and affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1960.

But the new system quickly acquired a flaw that later became a powerful advantage for employers.

In 1938—just one year after the Supreme Court upheld the Wagner Act —the Court ruled that while workers could not be fired for striking, they could be “permanently replaced,” a distinction with little practical difference. For much of the post-World War II period, employers generally tolerated unions in sectors where they were already established. But in 1981, President Ronald Reagan summarily fired the striking federal air traffic controllers. Reagan’s actions announced a turning point in the federal government’s attitude toward workers’ rights, and employers quickly adopted more aggressive tactics against unions and strikes.

Decades of conservative and pro-management decisions by the federal courts and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) have now turned the law upside down. At the bargaining table, the threat of replacement dovetails with legal rules that give management unilateral power to implement its last offer on declaration of impasse. Those rules have made it easier for employers to reach impasse and then simply impose their desired terms and conditions. In effect, we have returned to a pre-New Deal policy of judicial repression. The government may no longer send in troops, but ruinous legal and financial penalties threaten unions that go beyond tight restrictions on collective action. The outcome has been a dramatic drop in the number of strikes.

The consequences affect all Americans. Without protection for strikers’ rights, workers have lost an essential countervailing force against the power of corporate employers. The ability of unions to act in the workplace has been eroded, and the pre-New Deal imbalance in the labor market has returned along with its damaging effects. Studies have shown that the decline of unionization has contributed directly to the problem of widening income inequality in the United States.

This brings us back to the striking public school teachers. In the states where walkouts took place last spring, the law provides few or no collective bargaining rights for teachers and strikes are forbidden. Because of that, the teachers’ struggles are actually more typical of the new legal constraints and economic inequality that all American workers increasingly face. How were they able to succeed?

Part of the answer reflects a changing economic and demographic structure. In West Virginia, public school teachers now outnumber coal mining jobs by around 40 percent, the state’s public employee health insurance plans cover one in seven residents, and in many rural counties the school district is the single largest employer. When 20,000 teachers across the state all strike at once, it is not easy either to replace them or to outsource their labor. A central role was also played by the striking support staff, including bus drivers and cafeteria workers, whose jobs are vital to the daily functioning of the schools. With empty classrooms, local school administrators simply closed down their districts; hence the workers technically did not violate the law against strikes.

The walkouts, however, were not aimed at the districts. They were acts of mass civil disobedience and political protest by workers with their communities against their state governments. West Virginia has a long history of labor militancy associated with the United Mine Workers of America, but decades of employment decline in the coal industry have decimated the state’s economy and in 2017 the poverty rate reached 17.9 percent, the sixth highest in the nation. Teachers and their communities have felt the pinch, enduring years of state budget cuts to public education, health, and human services, even as taxes on corporations were reduced. By 2016, teachers had gone nearly four years without cost-of-living raises and average salaries ranked 48th out of 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Such grievances provided the grounds for protest, and in West Virginia, the walkout relied on strong internal solidarity among state branches of the American Federation of Teachers, the National Education Association and the West Virginia School Service Personnel Association representing support staff. Strike votes were held school-by-school to keep teachers involved and ensure support across the state’s 55 counties, while social media and mobile internet allowed for swift grassroots communication. Strikers also understood the importance of outreach to parents and community members. Around 75 percent of West Virginia teachers are women, paralleling national patterns, and their local ties and personal networks helped sustain momentum and public support. Before the strike teachers spent weeks talking to parents, and during the walkout they worked to make sure that kids who depend on school meals would be fed.

As traditional strikes and union organizing have become harder, labor activists have explored alternative tactics and forms of organization. One new tactic is to use limited, symbolic strikes of one or a few days’ duration, intended not so much to impose direct economic costs but to dramatize the dispute and bring it to public attention. Such tactics are often combined with community-based outreach and alliances with churches, advocacy groups, and corporate responsibility campaigns addressed to the consuming public. Like the school teachers’ strikes, these actions also sometimes target government or otherwise support campaigns for public policy reforms. The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) pioneered this strategy in the 1990s in its Justice for Janitors campaigns and it has been a key in the recent wave of strikes by fast-food workers in the “Fight for $15” movement to raise the minimum wage.

Government regulation can only reach so far, and an organized workforce remains in the best position to monitor, negotiate, and enforce standards on the job. Without the countervailing collective power of workers in the workplace, the pattern of increasing income inequality is likely to persist. And without a functioning system for union recognition and collective bargaining, labor protest is also likely to continue, albeit in unpredictable ways. The historical record shows that conflict happens in the employment relationship. The question for policy is, what means do we have for resolving it?

Send A Letter To the Editors